Even though his major achievements are long behind him, it came as little surprise to see the septuagenarian Paul McCartney headlining last month's jubilee concert. It seems that for almost any public celebration the aged and established are given pride of place. Filling the drive for exciting, original art with re-releases and comeback tours, the old becomes new, and the new are told to wait patiently for a turn that may never come. Our society is held in the grip of a hyper-nostalgia for a past that has become present.

At the Olympics, young, fit athletes will compete to demonstrate the greatest talent. The artists performing alongside them, however, are likely to be the same old faces remembered from their long-ago heydays. The Young British Artists continue to dominate the visual arts. We attach the label "young" to them, even as the Tate Modern holds their retrospectives.

The last 20 years demonstrate a rapid turnover of spin-offs, promoted by creative industries unwilling to take chances on risky new ventures. Desperate to stay afloat, publishers and record labels pressure their young artists to be mostly like the old ones. Take, for example, the noughties' plague of Beatles-a-like "indie" bands. Or the yawn-inspiring, endless literary fascination with the alienation of the ordinary bloke.

How have we got here? The mainstream's resounding silence implies that the under-30s are prioritising Pinterest, or whatever this week's social media craze is, over creative activity. Certainly youth unemployment and high housing costs are driving more than economic misery. Barren economic prospects also affect the production of culture. As the cost of living rises year on year, producing pioneering works becomes more challenging.

The real task for young creatives is to earn the institutional support and respect that will allow for any sort of longevity. For those who have something genuinely original, new, and different, however, it is institutional support that is least forthcoming – made even more difficult by the fact that society's disposable income remains concentrated in our parents' hands.

Luckily the new generation are not idle. This generation is producing work that evokes, provokes or intrigues in a way that categorically avoids ennui.

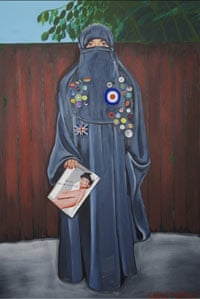

Radicalised by wave upon wave of discriminatory coalition policies, this generation is making art that draws on contemporary activist fervour, giving British political art a healthy shake-up. Recent graduate Sarah Maple's satirical mixed-media work speaks from the perspective of a British Muslim woman, providing a much-needed voice from within a group more frequently spoken about by others. Self-portraits such as Blue, Badges, Burka depict the covered Muslim woman as an autonomous individual – subverting earlier pop cultural representations in direct challenge to contemporary fears.

Politically conscious hip-hop is on the rise, led by collaborative groups such as The Peoples Army. Registering the disenfranchisement of the young, Peoples Army co-founder Logic writes lyrics that speak protest to power.

Call For Revolution locates itself within post-student protest disillusionment and anger, suggesting (if optimistically) the need for a global youth political awakening.

Also worthy of note is the zeitgeistily titled "Lolitics", a radical political-comedy event series hosted by Chris Coltrane. From jokes about extreme privatisation ("rumour is, from Whitehall, that they're thinking of privatising dubstep … in this time of austerity, can we afford to drop wobs at the rate … that we're dropping them?") to vaginal orgasms, Lolitics is a much-needed return to the biting, anti-establishment rant.

Fluidity and fusion are also trends invoked by today's young artists, perhaps against a society ever-more structured along class and income lines.

Welsh playwright Dafydd James's successful Llwyth/Tribe worked partially due to its linguistic hybrid form: a mixture of English, Welsh and Wenglish. Similarly, Micachu (and her band the Shapes) melds imagination and the catchy tune together into a blend of experimental "pop", using homemade and customised instruments to create textures that bring invention to genre-defiance. Anathema to an industry that thrives on the pinned-down demographic, Micachu collaborates extensively, mixing electro with grime, weird hoover samples, and even classical.

Any rumour of the death of the British creative establishment is premature. Its significance may have declined as self-dissemination of material, through Tumblr, through Twitter, now takes precedence over "official" channels. Nevertheless, industry retains its stranglehold over creation. New ideas are being produced but though older generations don't appear to be listening, we are giving it our best to make sure we're heard.