On the night Donald Trump won the U.S. presidency, Patrick Ottensmeyer sat glued to his living-room television until 3 a.m.

It wasn't only civic interest that kept him transfixed: Mr. Ottensmeyer is the chief executive officer of Kansas City Southern Industries Inc., a 130-year-old railway that reinvented itself in the 1990s as a prime conduit for commerce between the U.S. heartland and the rapidly opening Mexican market. And the man on Mr. Ottensmeyer's TV had just won the most powerful political office in the world on the back of a promise to build a wall along the Mexican border and tear up the North American free-trade agreement.

The next day, Mr. Ottensmeyer, a brown-haired, round-faced man, watched the stock market wipe out $1-billion (U.S.) in his company's market capitalization. He bashed out a memo to employees, trying to reassure them that KC Southern could navigate the new reality in Washington.

"Our stock was down 12 per cent. Our Mexican employees were … 'What does this mean? What's going to happen?'" Mr. Ottensmeyer recalls in an interview at KC Southern's headquarters, a postmodern brick-and-green-glass building on the edge of this Midwestern city's downtown. "My main message was really: I'm going to do everything I can to engage. We're not going to sit back and wait to see what happens."

Founded in 1887, KC Southern spent its first century as a regional railroad in the U.S. South and Midwest. In 1996, two years after NAFTA came into force, the company bought the rights to operate a large chunk of Mexico's railway network from the government. Today, its tracks run like a spine down the centre of the continent, connecting the U.S. heartland to Mexico City and ports on both of Mexico's coasts.

"Any way you look at it … 50 per cent of our company is in Mexico: 50 per cent of our route miles, our employees, our revenues, our carloads," says Mr. Ottensmeyer, who wears a lapel pin with the U.S. and Mexican flags.

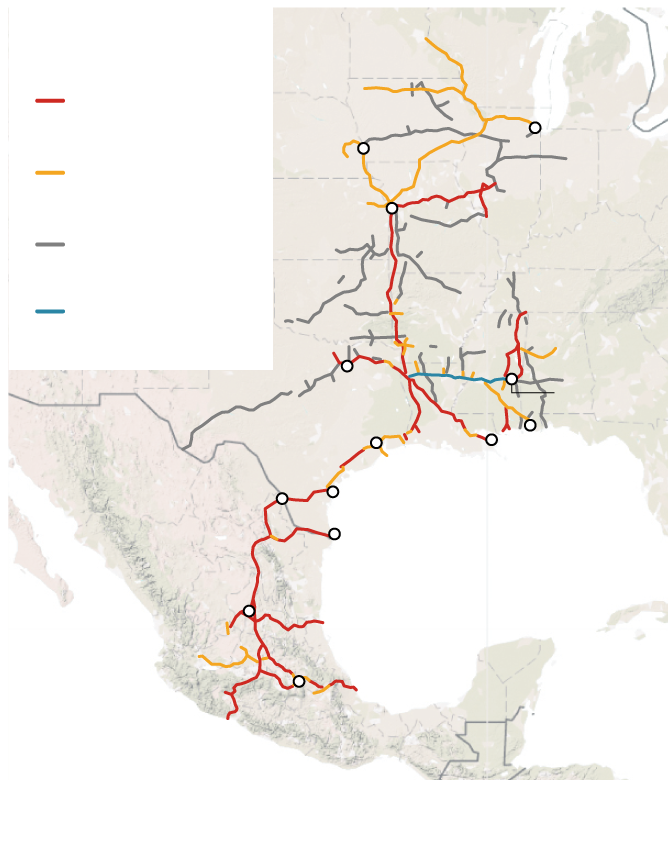

Kansas City Southern

Railway network

Lake

Mich.

Kansas City

Southern track

Omaha

Chicago

Haulage/

trackage/leased

Kansas City

UNITED

STATES

Shortline

Network

Meridian

Speedway

Dallas

Meridian

Houston

Mobile

New

Orleans

Laredo

Corpus

Christi

MEXICO

Brownsville

Gulf of Mexico

San Luis Potosi

Pacific Ocean

Mexico

City

john sopinski/THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCEs: kansas city

southern railway; google

Kansas City Southern

Railway network

Lake

Mich.

Kansas City

Southern track

Omaha

Chicago

Haulage/

trackage/leased

Kansas City

UNITED

STATES

Shortline

Network

Meridian

Speedway

Dallas

Meridian

Houston

Mobile

New

Orleans

Laredo

Corpus

Christi

MEXICO

Brownsville

Gulf of Mexico

San Luis Potosi

Pacific Ocean

Mexico

City

john sopinski/THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCEs: kansas city

southern railway; google

Minn.

Wis.

Lake

Mich.

Kansas City Southern

Railway network

Iowa

Kansas City

Southern track

Omaha

Chicago

Neb.

Haulage/trackage/

leased

Ind.

Kan.

Ill.

Kansas City

Shortline

Network

Ky.

Mo.

Meridian

Speedway

UNITED

STATES

Okla.

Ark.

Ala.

Miss.

N.M.

Ga.

Texas

Dallas

Meridian

Houston

Mobile

New

Orleans

Laredo

Corpus

Christi

MEXICO

Brownsville

Gulf of Mexico

San Luis Potosi

Mexico

City

Pacific Ocean

john sopinski/THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCEs: kansas city southern railway, google

The rail network is only the most concrete illustration of how tightly bound Middle America has become to its southern neighbour under NAFTA.

Midwestern farmers supply the corn that makes Mexican tortillas and the soy that feeds Mexican cattle. American factories provide parts to auto-assembly plants south of the border. Those cars, along with loads of other goods – from clothes to beer – are shipped back north to stoke the world's most voracious consumer economy.

During the election campaign, Mr. Trump portrayed the Midwest as a place suffering because of NAFTA, dominated by shuttered factories and dying mill towns. But the picture is more complicated: Canada and Mexico are by far the region's largest export markets, buying a combined $136.2-billion in goods and services from the Midwest last year, an increase of 194 per cent over the 23 years the deal has been in place.

As the NAFTA renegotiation looms, with talks set to start in mid-August, the economic interests of the U.S. heartland – which voted overwhelmingly for Mr. Trump – are largely aligned with those of Canada and Mexico, and rely on commerce continuing unobstructed between the three countries.

"The largest commodity that we move … is southbound, and it's grain coming from the upper Midwest," Mr. Ottensmeyer says as he points at a map of KC Southern's line sitting on a conference table in front of him: "All these red states in the middle of the country."

At Lowell Neitzel's Kansas farm, 45 minutes west of Kansas City, Kan., green corn stalks sprawl across thousands of acres beneath a blazing sun and clear sky. Come fall, much of what comes from this ground will be headed south to feed Mexico's burgeoning middle class. To Mr. Neitzel, the value of NAFTA is clear, and he seems a little surprised at how heated the rhetoric got during the campaign.

"When they start running for office, you just never know what they really mean or if they're just saying stuff with smoke and mirrors," says Mr. Neitzel, a slim man with dark, close-cropped hair. "It's foolish for them not to realize how important NAFTA is to us."

The 36-year-old is a fourth-generation farmer. He met his wife at agriculture college and now works a farm founded by her great-grandfather, along with his wife's parents, brother, uncle and aunt. If they choose to farm, his nine-year-old son and three-year-old daughter will be the fifth generation.

Mr. Neitzel says he hopes someone can show Mr. Trump the value of market access to Mexico: "You've got to be kind of optimistic that maybe somebody will get his ear and make him listen and make him realize."

Lowell Neitzel checks on the condition of a plot of sweet corn in Lawrence, Kan.

Nick Schnelle/The Globe and Mail

Lucas Heinen runs through the math of farming as he sits in an outbuilding on the land he works near Everest, Kan., about an hour north of Mr. Neitzel's operation. Planting an acre of corn costs about $550, between the seed, herbicide, fertilizer, rent, fuel and equipment. If the price of corn is $3.50 a bushel, this means that the first 157 bushels an acre produces serve only to cover costs. With 160 to 200 bushels an acre, the profit is small.

"Margins in farming are historically nothing. It's a competitive enterprise: We bid the profit out of anything. I think I can make a dollar an acre on something; someone else might be happy to make 50 cents. That's the way it works," says Mr. Heinen, a tall, gregarious 37-year-old who has worked the land most of his life – with the exception of a few years getting an agronomy degree at Kansas State University and working as a crop scout. A married father of four, he's passing along the tradition to his children. His oldest, 14-year-old Sam, is off clearing locust-tree sprouts from a hay field as we talk.

Terry Vinduska, 66, who farms near Marion, Kan., says he hopes he can just break even most years. Domestic demand for corn is flat, meaning he needs the export market to stay afloat.

"From the very beginning, I thought 'Where are these guys coming from?'" he says of the tone of the anti-NAFTA pledges during the election. "We need every bit of demand we can get."

Mr. Vinduska, Mr. Neitzel and Mr. Heinen voted for Mr. Trump. And they are certainly in the majority among their peers: He carried Kansas with 57 per cent of the vote and utterly dominated rural and small-town America.

Mr. Vinduska laughs when asked why he gave his vote to a man who repeatedly slammed a trade agreement that's so important to the farmer's livelihood. "We're getting way off of agriculture and way into the political realm," he says.

Mr. Vinduska explains that he liked Mr. Trump's promise of reducing red tape, particularly his pledge to overhaul the Waters of the United States rule. The Obama-era environmental regulation, which sought to give the federal government more power to regulate rivers and lakes, was unpopular with farmers, who feared it would make irrigation and other agricultural practices more difficult.

"To be perfectly honest, I saw him as the lesser of two evils. Now, is that a good reason to vote for someone? No … Does that mean I like everything about him? Of course not. But I just felt like the overall picture was better for me with Mr. Trump," he says.

Mr. Vinduska also points to the Midwest's social conservatism as another dividing line that pushed it in Mr. Trump's favour: Despite his previous support of abortion rights, Mr. Trump adopted the GOP's standard anti-abortion position during the campaign.

Mr. Neitzel heaves an audible sigh in discussing his vote for the President. "He was less regulations and he was more conservative," he says, adding there were also "trust issues" around Hillary Clinton.

For Ivry Karamitros, the election was a wakeup call. Director of Kansas City's World Trade Center in Missouri, she is used to advising companies on the benefits of jumping into the export market by selling their goods to Canada and Mexico. Kansas City is in an ideal place for that, sitting at the crossroads of north-south and east-west highway and rail corridors.

"We really need to do a better job of educating the public as to the drier aspects of free trade," she says. "It became very apparent there is obviously a messaging issue, that people are not educated on the facts and how important NAFTA is and what that means on a local basis in our economy."

Ms. Karamitros's organization has been holding educational events with business leaders, academics and trade officials and running online seminars in a bid to build public support for NAFTA.

The warehouses of Scarbrough, a trucking company in a suburban Kansas City industrial park, are visual representations of the integrated economy. In one of the cavernous, 20,000-square-foot buildings, Adam Hill, the company's lanky, boyish vice-president of operations, points to cases of tequila trucked in from Mexico in one corner. A couple hundred metres away sits a flat of tents, flashlights and other camping equipment destined for a warehouse in Canada, where it will be used to fill Amazon orders. "You name it, we move it," he says.

Mr. Hill cites one example of how a single product crosses the border multiple times: Scarbrough imports plastic pellets from Europe for a U.S. factory that turns those pellets into plastic bottles. Then, Scarbrough ships those bottles to a Canadian whisky distillery to be filled with rye, which the company then moves back into the United States.

"It's neat to see the whole supply chain in action with several of our customers on each side of the transaction," he says.

And if Mr. Trump's supporters are apoplectic about NAFTA, Scarbrough's clients can't get enough of it. Kevin Ekstrand, the company's vice-president of sales, says part of the motivation to expand into the Mexican market was sheer business interest: A couple years back, Scarbrough brought in officials from a Mexican logistics company to hold a seminar in Kansas City about getting into that market.

"The place was packed with people wanting to know how to do business in Mexico," he says. "There was an 'a-ha' moment."

To Scarbrough, the logic of NAFTA is simple: Mexico can supply products at the same prices as China, but where it takes 30 days to import from China, Mr. Ekstrand says, the company can move a product from Mexico in two. And it's in the United States' interest to bolster Mexico's economy.

"If they're manufacturing more, their wages increase, they become consumers, they develop a middle class and now all of a sudden, they're consuming U.S. products. We export intellectual-property rights and insurance and education materials. If we can build up a country that's sitting right next to us that needs all of those things, they're going to start consuming them and then we're going to reap the benefits," he says.

Not all lawmakers seem to understand how integrated the economies are. Mr. Hill has met with senators and congressmen to explain the importance of trade – and particularly complex supply chains – and says he's often met with blank stares.

"To sit down and to have those conversations is like deer in the headlights. Most people walk into a store and they just say 'Oh, my product is here and it was made in China.' They know nothing else about what happened, they don't understand what it means," he says.

The bottle of whisky is a small-scale example of what is happening across industries. While some of the $1-trillion in annual NAFTA-zone trade is accounted for with straight export-import transactions – a product is made in one country and sold in another – it is often more complicated. According to research by the Mexico Institute at the Wilson Center think tank in Washington, U.S. and Mexican industries in 2014 traded $268-billion worth of intermediate goods – components to be used to manufacture finished products, from car parts to fabric for making clothing.

The argument goes that such efficiencies make the companies better able to compete internationally, which ultimately helps the people who work for them.

Not everyone sees it that way.

At the union hall across the street from Ford's sprawling truck-assembly factory in a Kansas City suburb, a sign jokingly warns that foreign cars found in the parking lot will be towed. Inside the hall, Jason Starr, president of the plant's United Autoworkers local, says the changes wrought by NAFTA have directly affected the wages and working conditions in the industry.

Ford uses the threat of moving to Mexico to extract concessions in bargaining, he says. And competition with Mexico is also helping drive the push for anti-union "right to work" legislation. Missouri just passed such legislation earlier this year.

"Prior to NAFTA being passed, our primary focus in collective bargaining was making gains for our membership. Post-NAFTA, we've had to adapt our negotiation style to make sure that we were getting product investments," he says. "It's a huge leverage point for them, something that is always brought up."

There may be more jobs over all in the auto sector, Mr. Starr says, but what is that worth if the employment is offered for lower wages and harsher working conditions? Over the years, for instance, the auto companies have got out of parts manufacturing, outsourcing the jobs to smaller companies, he says.

"A lot of those manufacturers in auto parts have become different companies, and they employ temporary workers. They're still in auto, but they don't have the big benefits or the pay structure that we have," adds Tony Renfro, vice-president of the union local.

In Mr. Starr's view, NAFTA has eroded American employment standards. Instead, he argues, trade agreements should oblige other countries to rise to the United States' level – by action such as enforcing tougher labour and environmental laws.

"We can either bring ourselves down to the standard of Mexico or China, or we can work with them as they bring themselves up," he says. "There aren't a lot of folks in Mexico that can go out and buy a brand new F-150."

Mr. Starr, who has a large photograph of Harry Truman – the Democratic ex-president and native son of Missouri – on his office wall, didn't vote for Mr. Trump. But some of his members did, and he understands why.

"He spoke to working-class values. A lot of our own membership ended up throwing their support in his direction because he did talk about issues that they knew directly impacted their ability to provide for their families," he says.

But if Mr. Starr's colleagues will be hoping Mr. Trump steers straight ahead on his campaign promise to overhaul or abandon NAFTA, others in the heartland will be praying for a U-turn.

And this may be the key to NAFTA's salvation: The argument in favour of the trade deal sounds more persuasive to the Trump administration coming from supporters.

Mr. Ottensmeyer, the Kansas City Southern CEO, points to the story of Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue, on his second day on the job, showing Mr. Trump a map of all the agricultural exports heading from the Midwest to be exported in the NAFTA zone. His intervention was, by some accounts, a key factor in the President backing down from a plan to trigger Article 2205, the process for pulling the United States out of NAFTA.

It's the same message Mr. Ottensmeyer says he has been pressing home in his meetings with administration officials – including Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross, the point man on the NAFTA file: That much of the U.S. economy relies on the pact.

He's also been co-ordinating with Mexican officials. On April 26, the day Mr. Trump's musings about 2205 were leaked to the press, Mr. Ottensmeyer was in Mexico City. He was en route to a meeting with Juan Carlos Baker, the Mexican government's head of foreign trade, when one of his subordinates sent him a link to a Politico story on the draft order. Mr. Ottensmeyer turned to the head of KC Southern's Mexican operations and joked "I need to know what floor this guy's office is on – can I survive the fall?"

In Mexico, after all, Mr. Trump's pledges to tear up NAFTA and build a wall on the border have touched off political turmoil. President Enrique Pena Nieto's administration is caught between the forces of business, which want the accord preserved at all costs; the public, which wants the country's leaders to stand up to Mr. Trump; and newly emboldened protectionist politicians.

When the meeting began, Mr. Carlos Baker was more taken aback than angry.

"He actually said, 'We're trying to hold a country together.' And I kind of felt small at that point," Mr. Ottensmeyer said. "I'm worried about the next quarter's earnings, and you're trying to hold a country together."

That national perspective isn't lost on corn farmer Mr. Vinduska, who sees free trade as a natural extension of the sort of competitive capitalism he lives with every day – and that has made America the world's largest economy.

"I compete with my neighbour in that whoever is more efficient is going to make more profit," he says. "There are going to be small individual winners and losers with any trade agreement. So you have to look at the overall big picture."

MORE ON NAFTA