“There’s no word that describes autism in the Somali language," says Nura Aabe, 35.

It’s something the autism campaigner and mother of five has been grappling with ever since her 18-year-old son Zaki – short for Zakaria Mohamed – was first diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder when he was 2 and a half.

"At the time I had not heard of autism before," she says. "I struggled [with] the whole process because 'autism' is an unknown word in the Somali language. It was a condition no one knew about and [that] meant it came with stigma and barriers at every level.”

Life couldn’t be more different for Aabe now. When we first meet, she has just moved into a new office at a family centre in Bristol, with a small playground at the front. She is wearing a floral hijab and has a selection of leaflets on the table, including a few from Autism Independence, the social enterprise she founded in September 2013. “It is my destiny to climb the highest," the tagline reads, beside a logo of a purple hand with a smaller black hand inside it.

Her company raises awareness of autism, and provides a support network for families hailing from migrant communities affected by it. It is due to become a charity in the next few months.

One in 100 people in the UK are on the autism spectrum, a lifelong developmental condition affecting how a person communicates, relates to others, and make sense of the world. It means autism is a part of daily life in this country for 2.8 million people, including families with a member who is affected, according to the National Autistic Society.

When Zaki was diagnosed, 16 years ago, Aabe’s life changed. She felt isolated from her Somali friends and family, who told her everything was fine, and from health services she wasn’t familiar with. “I became a woman who was very afraid and stayed in most of the time and struggled to be a part of the community,” she says over tea and biscuits. Her transformation into “someone now who campaigns for autism and [is] on a journey” has been a deeply personal one.

Aabe came to the UK in 1990 as a refugee fleeing civil war from Hargeisa, Somaliland, when she was 8 years old. She grew up in Bristol. She got married and had Zaki, her first child, soon after. “I was very young and was delighted: He was a beautiful, very happy, very smiley baby. A lovely little baby.”

Zaki was not visibly different from other children, which made understanding autism more difficult for Aabe and her family.

“I think at the age of a year and a half he deteriorated. … He would not look me in the eye. He would sit behind a door, he lost all the words and even the bubbling vocal noises he was making.

“He wasn't making eye contact, he wasn't interacting with other children, he would stare at moving lights for a long time, play differently to a baby that was the same age as him. He would line things up rather than imagine how a toy would work – he would line up cars, rather than pretend he was driving a car as any child who hasn't got autism would do.

“The difficulty was I really did not understand all those behaviours, because back home there's no such role that tells you about child development. There's no psychologist, there's no speech and language therapist, there's no occupational therapist, and so there's no child development tickboxes that you follow, which really put me in a vulnerable position as I have never seen that in my family.

“The space we had in my childhood was all about learning from the environment and from the community and people around me. Whereas here in Britain, you're always on your own in the house and have to sort of create that space to develop your child's thinking.

“I wasn't going out enough because of the stigma that came with my son's disability, I didn't feel confident enough to do that. All I did was clean him, feed him, and then left him on his own because I didn't know how to help him and didn't know what was wrong with him.”

Aabe says her parents reassured her, saying her son was born healthy and a good weight, and that she shouldn’t worry about what others told her. She felt she was getting conflicting messages from her loved ones and health practitioners, but preferred to hear what her family had to say as she felt they knew best.

Zaki was diagnosed at 2 and a half when a health visitor came to visit Aabe’s younger twin babies and suggested she take him to the local nursery. It was there that her son began to have assessments by professionals and the word "autism" came up.

The idea seemed alien to her. Feeling confused, she chose not to engage with health services. “All the language they used meant nothing to me. They did explain, but I didn't really understand what they were trying to say. Like I said, back home there's two things – normal people and not normal people.

“When I went to my mother she said, 'I've never heard of autism,' and that was a really difficult time for me because Zaki was different from my sister's children and I knew that there has to be something wrong.

“But as Zaki got older it got real that he has got a serious problem, and that I had to learn about autism.”

She recounts the way her son would wake up in the middle of the night and destroy household equipment and furniture, which meant every room in the house had to have a lock and his bed had to be replaced at least twice a year – a story she shares in the leaflets she gives to other parent carers.

Research suggests autism may be overrepresented among some migrant communities, and population-based studies from the US and Finland stress that culturally appropriate help needs to be given. Fiona Fox, a senior research associate in qualitative social science at University Hospital Bristol NHS Foundation Trust, examined autism in the Bristol Somali community with Aabe. Somalis are the second-largest migrant community in the city.

Fox tells BuzzFeed News that there are clear reasons why people from migrant communities might not make use of services. “One of the biggest problems people face is there's no word for autism, and so it's hard to communicate with family and friends,” she says. “Even when they do tell, they get a lot of resistance and people telling them not to worry and not to seek help. Often people are told not to go to the doctor.”

She adds: “It hinges on the difficulty in communicating even within families. Quite often the mother knows the child needs help but the father won't accept it. It’s bound up in the stigma about mental health and disability in general, and not just the lack of a word. As Nura says ... and other interviewees said, the understanding is there’s either ‘normal or not normal’, and there's nothing in between.”

It took Aabe five more years before she finally got support for Zaki, when he was 7. “It was a long process," she says. "I accepted that Zak has got autism, and that Zak is different, but I can get him help so I need to learn about autism and I need to empower myself.

“When I did it was a breakthrough for us. It was like, ‘this is it’.”

From then on, she absorbed all the knowledge she could. “I would be on the computer for many, many hours trying to understand, trying to research.” She went to the first National Autistic Society conference in Birmingham. “It was three days long and I met a lot of people. All we did is talk about autism and it was heaven.

“This gave me hope as I was not the only one – there are many, many people out there including doctors, charities, organisations who were talking about autism. Just autism.”

She started implementing some of the ideas she had learned. “So I started using visuals, little cards with pictures, picture communication, and it took me many, many years for him to look at me in the eye and see me.”

She met other parents with autistic children and learned that many had shared her experience. She wanted to help them too. “Many women were in the same position as I once was, and I had to do something about it. I couldn't just watch when people were contacting me and saying, ‘I have a child with autism, can you advise me?’

“That breaks my heart, to see people hide their children.”

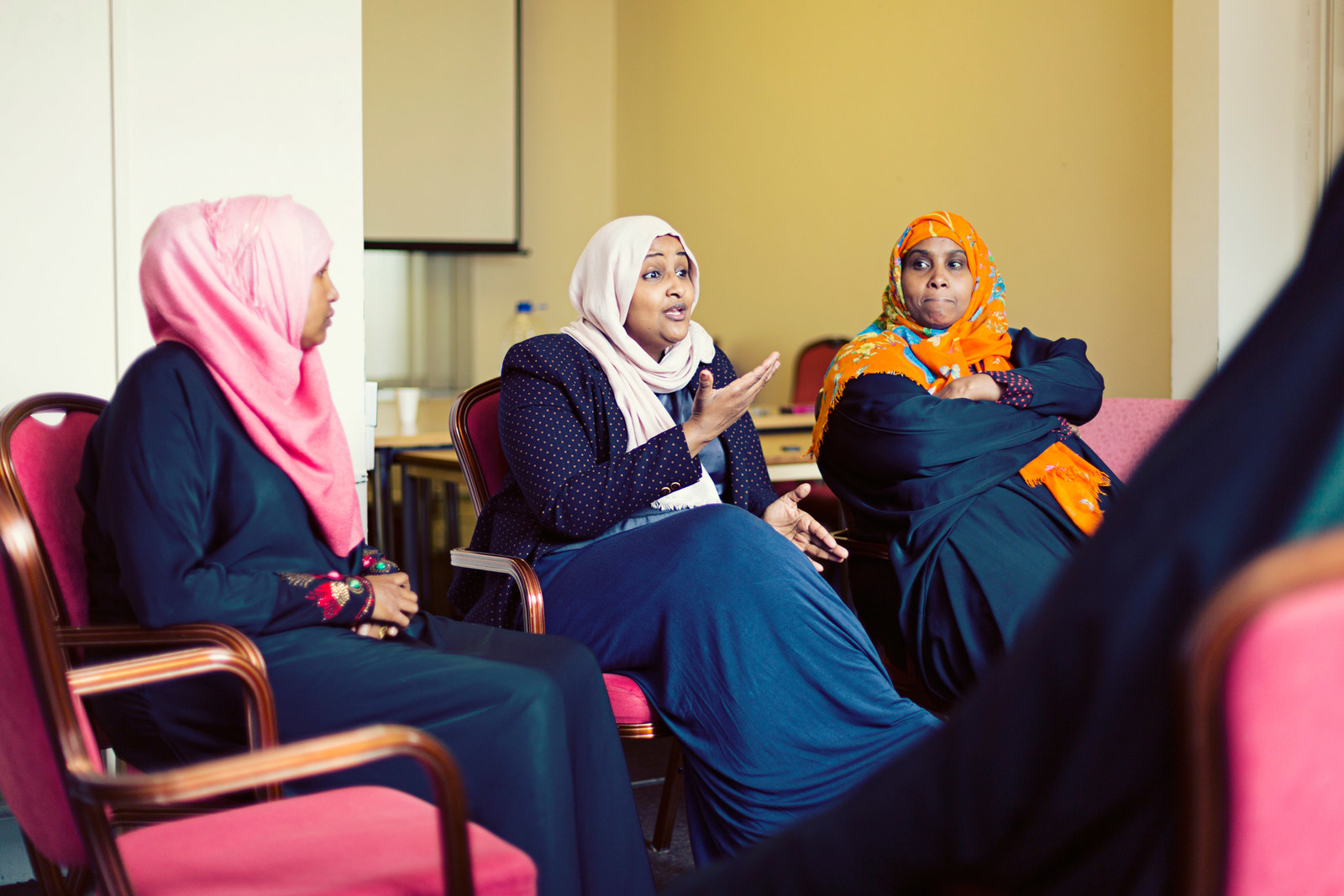

She started a group for 15 families in the Bristol area who would attend weekly drop-in sessions with activities for parents and children. Now she works with 50 families, who are all Somali.

Carol Povey, director of the National Autistic Society's Centre for Autism, says getting support from public services can be a hugely stressful process, and the centre’s 2014 research suggests it can be even harder for people from black and minority ethnic backgrounds.

“In order to break down these barriers, we need to improve the public understanding of autism and the experiences of autistic people and families from different backgrounds and cultures,” she tells BuzzFeed News. “This must be accompanied by greater efforts by decision makers, service providers and faith and community groups to listen to families from BAME backgrounds and to produce culturally appropriate support.”

Kath Fryer, a Bristol regional officer for Cerebra, a charity for children with neurological conditions like autism, has worked with families for 15 years helping to develop a support network. She noticed that black and minority ethnic families were underrepresented at some of its events, and has worked with Nura’s group on joint events such as a sleep advice service. Together they have run four sessions since July 2016.

“It's been brilliant, as Nura has been there to translate and relate people's experiences as an advocate for parents who were there, but didn't feel able to talk about their experiences,” Fryer tells BuzzFeed News.

“I've learnt that it's about building trust, and I think in Nura's community people like to have a person they know, [have] met, and trust in order to talk about some of the challenges they face. And that takes time building that relationship, and I totally understand that.

“I think Nura's passion, her commitment and energy, has been central to building up those links.” Fryer adds that language and cultural differences mean that “asking for a referral for a social worker or outside help, or [help from] the family, might be viewed differently in another culture. It might be questioned, it might be judged.”

It’s been a whirlwind of a year for Aabe. While currently writing a proposal for a PhD exploring autism and ethnicity, she has been collaborating with Bristol University and the NHS. She has published two papers on autism in the UK Somali migrant community, with another joint report with HealthWatch published in May. She has spoken in parliament about autism in the Bristol Somali community in November, and is planning to host a workshop raising awareness in San Francisco this year.

She’s also telling her story through a play. Yusuf Can’t Talk, which she created with other Somali mothers from the UK and Rotterdam in the Netherlands, was first shown onstage at Acta community theatre in Bristol. She is now taking a one-woman version of the show across the UK in which she performs and narrates her journey.

Aabe beams when she talks about the progress her son has made. Once unable to talk, he is now 18 and attending a Steiner special needs school, as well as a Kumon learning centre for extra support with maths and English. “He was in his school play today and that was really, really lovely,” she tells BuzzFeed News.

“He leaves in the morning for school and closes the front door, and says, ‘I'm going to stay in the taxi on my own.’

“When I ask 'what will you like for dinner', he says, ‘I'll have tuna with spaghetti.’”

She says she has come to appreciate Zaki for who he is, saying: “I completely took out the autism [from] our relationship and that was beautiful. I would like parents out there to see their child and not the autism.” She adds: “You can forget about your child and be stuck in this mind of wanting the so-called normal life, this so-called normal way of life.

“Who is normal? We're all different – I have quite odd behaviour sometimes. And I don't see myself as different. I see myself as a powerful woman and that’s what we need to recognise as human beings.

“I have learned, and I've been seeing from other stories, [that] I need to be patient with him and need to repetitively be teaching him, that I need to be consistent with him. I need to reduce my language, I need to be really calm with him. I need to be grateful for anything he does, accept him and love him as my child.”

While her work is making a difference, there is much more to be done. Aabe has noticed an increase in the number of the families she works with refusing the MMR vaccination for their children because they fear it has links to autism, "but obviously that's not true".

"Because the number of Somali children with autism are increasing, people are trying to find answers and trying to think what could be the causes and reasons for it,” she says.

"Obviously that brings concerns from me, because there are obviously much more dangerous diseases we use MMR [vaccination] for.”

It is an issue that has recently seen severe consequences in the US, where anti-vaccine groups were blamed for the largest measles outbreak in two decades. In Minnesota, there have been 79 confirmed cases of the disease, mostly affecting unvaccinated Somali-American children, according to the State Department of Health.

"There needs to be some kind of community-led training support for families to build the understanding that there is no evidence that MMR is linked to autism from research," Aabe says.

Over the Easter break, she organised a residential trip for nine other families – including carers, mothers and children aged between 6 and 16 – to Exmoor National Park in Somerset.

“It’s important for us who have been hiding our children from one another,” she says, explaining how it was the first time many of her friends in the support group were able to have some time for themselves – get a massage, get henna done, and dance, with no responsibilities such as cooking or cleaning. It was the first time some of the children had got to go to the beach, at Lee Bay in Lynmouth, and visit Exmoor steam railway.

“It really meant families came together and they didn't feel alone any more," she says. "It was very calming for them to have that space and really think about things."

Fartun Noor, 32, went on the retreat with her 6-year-old daughter Afnam. “It’s nice, I need my people," she says. "We speak our own language, we understand each other and are in the same situation." She found out about Autism Independence through her neighbour, so had the additional support when Afnam was diagnosed last year.

Aabe wishes she had this sort of support when Zaki was younger: “I never really travelled, growing up with him. I knew how people would perceive me, I knew I didn't have the confidence.”

The moment that sticks out the most for her during the residential trip was when a parent who usually struggles to get her son to sit down saw her child “just going out and doing his own thing”. Aabe felt like she could relate.