On Tisha B’Av, Relationship Advice From Miles Davis

What the great jazz musician, and the sages of the Talmud, told me about idolatry, destruction, and making a marriage work

I was first introduced to the holiday of Tisha B’Av in my mid-twenties, living in Jerusalem. Though I’d grown up in a Reform household, I found myself exploring an Orthodox lifestyle, wearing a kippah and sporting the longest, thickest tzitzit I could find—they dangled from my belt to my knees, like a sparse hula skirt. At the yeshiva where I was studying, we learned the talmudic story of Kamza and Bar Kamza, wherein two neighbors whose rigid ways of seeing the world leads to disaster at a party: a misunderstanding leads to public humiliation. The relationship is damaged beyond repair, and before long, a personal squabble leads to community violence and ultimately, the destruction of the Temple.

I rolled my eyes at this story. The Temple fell because two people couldn’t get it together to see things from each other’s perspective? It sounded less like something out of the Holy Talmud, and more like the moral of an episode of Schoolhouse Rock.

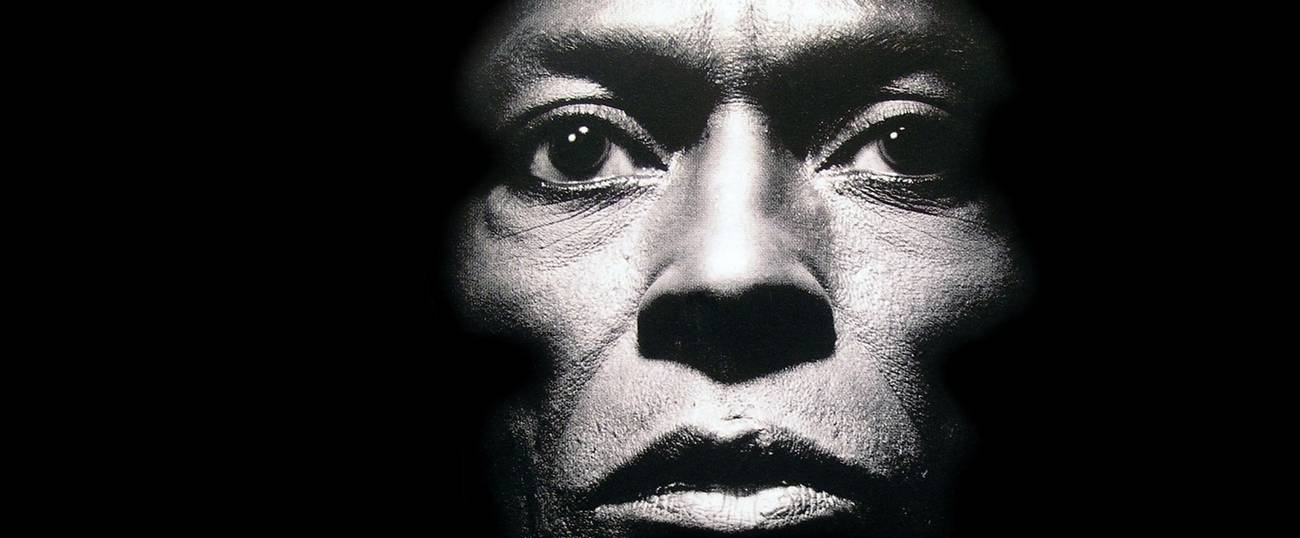

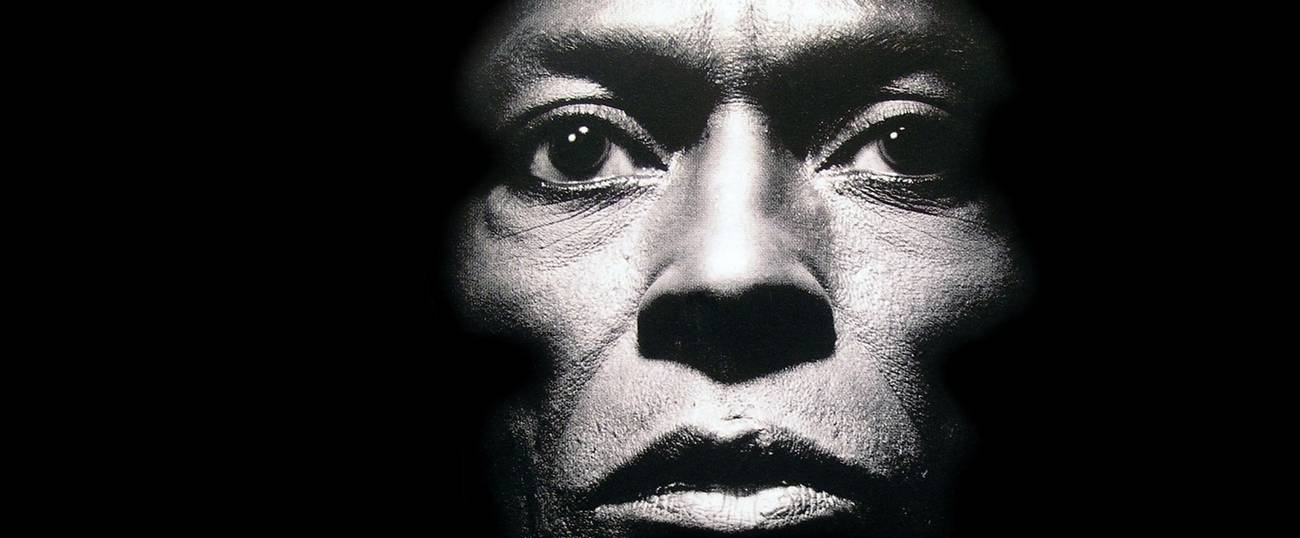

Then I got together with my first girlfriend. One afternoon, after she mentioned that she had never really understood jazz (a musical form I had long worshipped), I decided to make it my mission to show her the light. I sat her down, dimmed the lights, and put Kind of Blue by Miles Davis on the stereo. The instruments arrived one by one like guests joining a party: dreamy piano chords, then the insistent, repeated bassline, then the trumpet and saxophones, the splash of drums, and finally, the first solo, pouring from the speakers like a long stream of wine. I was in bliss.

Nine minutes and 24 seconds later, the song sizzled out. I turned to her and instead of being met with the beatific glow of someone who had seen the light, there was another expression altogether: profound annoyance. While I was on cloud nine, my girlfriend, it turned out, was not remotely into what she described as random, incoherent noise. I had never stopped to consider that she might not want to have an immersive encounter with Miles Davis forced upon her by her rigidly expectant boyfriend.

I was genuinely sorry for being inconsiderate, but secretly, I was devastated. I was certain the relationship was doomed, her refusal to join me in worshipping Miles Davis was the ultimate dealbreaker.

Nearly two decades later, I now see that I had made a classic rookie mistake. It’s a classic sign of immaturity to believe one’s passions are Truth for All: hockey, Quentin Tarantino, Raymond Carver, Star Trek, raw veganism, and, apparently, Cool Jazz. The forced Miles Davis listening session makes me laugh in hindsight, but it provides a useful metaphor for a serious error that we make, every day in all kinds of relationships: we forget that the other person is different from us and might not love all the things we love. We don’t make space for others to be who they are, we hang onto our own expectations, and believe we can control elements of the other person that are not in our control. Without meaning to, we set about trying to design the relationship, if not the other person, in our own image.

Well, there’s a name for that and it’s not a favorable one: idolatry.

I spent my thirties attempting to unlearn this bad habit and thankfully, eventually, thanks to the patience (or lack thereof, as the case may have been) of other girlfriends and an excellent therapist, I learned how to make better choices about what to expect from a partner. When I was 37 and met the woman I would go on to marry, I knew early on that what we had was something special. There were elements of our lives that were deeply compatible: our love of the written word, our passion for food, our commitment to family, our shared sense of humor, and our dedication to our Jewish heritage.

And yet, other elements weren’t as simple: I was shomer Shabbat in the traditional sense, and she was not. She was an omnivore with a particular affection for pork, and I observed strict dietary laws. Twenty-something me would have concluded that, despite all the good stuff, the relationship was doomed as we each brought different, seemingly incompatible Jewish identities to the table. For twenty-something me, the Temple of our relationship probably would not have lasted a month.

Through dialogue and openness, the woman who would become my wife and I made space for each other’s commitments, and in doing so, created some shared new ones. She learned to make delicious kosher versions of her favorite treyf dishes, and I learned that kiddush over a barrel-aged Manhattan in our neighborhood cocktail lounge might be exactly what I want after a long week. I find myself more interested in feeling the togetherness that comes from standing next to her in synagogue than I am in shuckling as hard as I can behind a mechitza. The result, today, is not halachic co-existence, wherein we each tolerate the other’s practices, nor is it a compromise, wherein I win some and she wins some. Rather, a new thing came into existence: a totally idiosyncratic Jewish life and home that neither of us could have previously imagined, one which is better than anything we could have planned individually.

While the sages teach us that the Temple fell due to “baseless hatred” and infighting between factions of Jews of Jerusalem, I don’t mean to suggest that my wife’s and my relationship provides an antidote to struggles within the Jewish community. I believe that there are times for groups and individuals to hold their ground and grapple with unresolvable differences. In my daily life, I’m grateful for the mistakes I made when I was younger. As a result, I’ve learned how unwillingness to see the world from the Other’s perspective can destroy a relationship, if not Jerusalem. And for that reason, Tisha B’Av for me is not a holiday of mourning and grief, but a yearly opportunity to look at all my relationships as Temples which will stand, year to year, only when I do the work to let my Other be who she is.

In the car together, my wife and I sing along to Buddy Holly, The Beatles, and other classics we both love on Spotify’s Oldies station. And late at night, while she reads or watches a T.V. show, we’ll smile at each other from across our living room, then I’ll lean my head back, pop in my earbuds, and listen to Miles.

M. Evan Wolkenstein is a high school teacher and writer in the San Francisco Bay Area. Turtle Boy is his first novel and winner of the 2021 Sydney Taylor Book Award. He tweets at @EvanWolkenstein.