Early last year, China announced a five-year plan to eliminate excessive capacity and lay off workers in the coal and steel industries, in a bid to restructure the world’s second-largest economy. This March, the government set a new goal of cutting steel capacity by 50 million metric tons (55 tons) and coal capacity by 150 million metric tons by year-end.

But reality is diverging from the rhetoric.

China just announced its GDP expanded 6.9% in the second quarter of this year, from April to June, according to the latest official figure. That has beaten analysts’ consensus estimates of 6.8%, and continues the encouraging trend shown by the previous quarter’s data, after concerns that the economy could slow further than it already has. China has said it is aiming for GDP growth of around 6.5% this year; the International Monetary Fund in June revised its forecast up to 6.7%.

But the driver of upbeat activity “remains all the things that China was trying to get away from like coal, steel,” said Christopher Balding, a professor at Peking University’s HSBC Business School in Shenzhen.

China’s steel production hit a record high this June, breaking the previous record in April, as construction demand and prices picked up. Riding on an expected summer uptick in demand due to electricity use, May coal output jumped 12% from a year earlier, the fastest growth rate in at least two years. Growth in industrial output also accelerated in June, beating market expectations.

China has said that it cut 65 million metric tons of steel capacity in 2016, and spent $4.4 billion on assisting the 726,000 workers affected by both steel and coal restructuring. The cuts are aimed at improving prices and industrial profits, as well as reshaping the economy.

It’s worth noting that you can cut production capacity without cutting production in China. A study commissioned by environmental nonprofit Greenpeace, published in February, showed that nearly three-fourths of the steel-capacity it recorded for China last year—85 million metric tons—came from mills that weren’t any longer in production to begin with. Meanwhile, the amount of restarted production and new capacity that came online came to 66 million metric tons, the report found.

In addition, the actual cuts that will occur this year could be in question too. The study reported more capacity reductions than China officially announced for last year. This could mean that a significant amount of capacity closure was not registered by the end of last year, noted Lauri Myllyvirta, energy analyst at Greenpeace in Beijing. The difference “could represent carryover to this year, making the actual amount of capacity that needs to be closed to meet the target smaller,” he said.

Meanwhile, a key indicator for Chinese blast furnaces that shows how much of the total operating capacity is in use is down from a year earlier, while steel output is up. How were steelmakers able to ramp up production while using furnaces less? One way would be if capacity, i.e. the number of blast furnaces that can be used, had gone up. “It certainly underscores that excess capacity remains and the industry isn’t out of the woods,” Myllyvirta said.

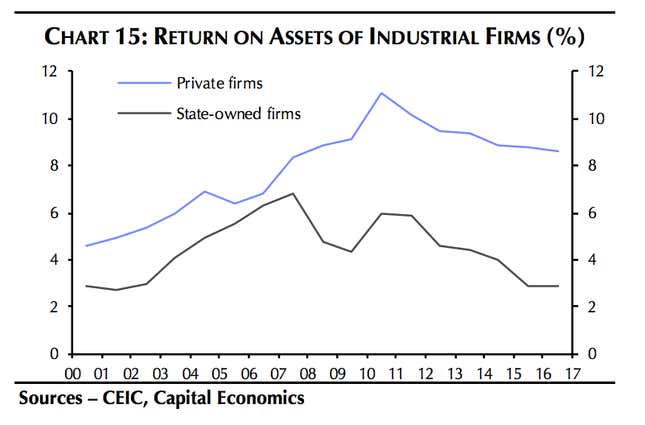

One of the major reasons behind Beijing’s capacity cuts is to reduce government support for struggling industrial firms that are disproportionately state-owned. These companies are so-called “zombies” which rely on rolling over their debts in order to survive. The chart below, from Mark Williams, an economist at Capital Economics research group, shows an increasing gap between the returns generated by state and private firms in industry.

So far Beijing is reluctant to get to the root of the misallocation of credit—a key concern given China’s high debt, and as loans continue to grow. That would involve allowing more actual bankruptcies, and job losses. Currently, 1,879 bankruptcy cases are being reviewed by Chinese courts, according to official data (link in Chinese). Of those, only 236 are state-owned firms. Breaking down by industry, only 46 are steel companies.

“Local politicians won’t get promoted for shutting down a loss-making steel firm, they get promoted for increasing GDP,” Balding said.

Because China’s Communist Party is slated to hold its 19th national congress, a twice-a-decade leadership reshuffle event this fall, China watchers aren’t anticipating any major policy changes before that. Historically, uncertainty is the last thing the Party wants ahead of big events. Over the past weekend, China’s top leaders held a two-day financial work conference, but the results announced appeared much less exciting (paywall) than many had speculated.

Last week, China revised its GDP calculation method, but the change is not reflected in the latest figure, according to the national statistics bureau. In June, Beijing also announced plans to make its own calculations of local-level GDP after three provinces–including the rusty belt region Liaoning–were found to inflate their GDP figures.