Most of the clothing Ross buys is Hanes, American Eagle or Costco's Kirkland brand ("very affordable"). The 20-year-old welder from Indianapolis only splurged on Carhartt because his boss told him to purchase some through the company's supplier for work. He liked the brand so much that he now owns a Carhartt hat and jeans, "like the kind Gary Johnson wears."

"I got them from work but the pockets are big so I like them," he says. "I wear [my jacket] anytime I'm cold. It's like my go-to outer layer."

Ross, who voted for Johnson in the last election, doesn't agree with many of Trump's policies, though he does think it's "refreshing to have a politician so efficient in keeping his promises."

Both Trump and Carhartt are, to Ross, effective.

A few states over in Michigan, Michael Montgomery echoes the same sentiment—at least about Carhartt.

"It's well-made stuff and it really really does wear well," he says. "It's for folks who need true work clothes."

Unlike Ross, Michael Montgomery works in an office, as a development and fundraising consultant. Growing up in Detroit, Montgomery can think of no brand that better represents his adolescence than Carhartt. Now a father of three, he finds himself wearing the brand to work on casual days. Like him, his kids grew up wearing Carhartt, and two still do. Montgomery went from buying the brand at the local hardware store to online, but his loyalty remains.

One white collar, one blue collar. But to the folks at Carhartt, Michael and Ross couldn't be more alike.

Carhartt has become shorthand for the heart of blue-collar America. It's had an enduring appeal to the nation's working class, which makes it no surprise that the brand has long been co-opted by politicians trying to prove their everyman bonafides. Sarah Palin allegedly once agreed to an exclusive interview with a reporter because they shared a love of the brand. The iconic jacket was front and center in Rick Perry's 2012 "Strong" ad, which features the former Texas governor talking about his Christianity and American values. Even former President Barack Obama was spotted wearing the gear during his three-day trip to Alaska in 2015 as an homage to the state's devotion to the brand.

Yet despite its appeal to right-leaning values, the reality of the brand's operations are a conservative nightmare: Since 1997 it's been predominantly produced in Mexico, rappers and Europeans love it, and yeah, maybe it likes hunting, but it's also into jazz festivals and celebrities. Carhartt has become the model for a brand that has matched a degree of progressivism with working class values, all without alienating its conservative white consumers.

The brand, it might seem from the outside, is a bit of a paradox. But to those who know and love it, it's simply a good product, beloved by the right and left alike.While other American companies are struggling to define "All-American" in a polarizing political climate, Carhartt hasn't gone out of its way to prove anything. It's won the hearts and wallets of consumers across race, gender, and occupation without so much as a team of ad agencies.

The secret? About 128 years of hard work and good luck.

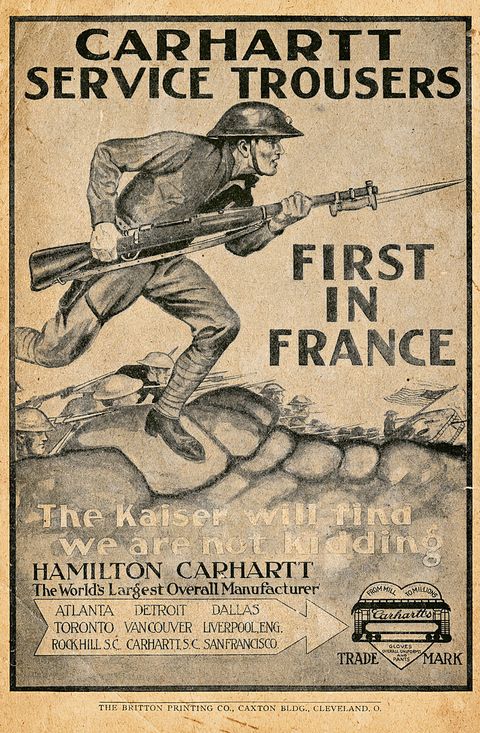

With only two sewing machines and five employees, founder Hamilton Carhartt established the clothing company in 1889 just outside of Detroit in Dearborn, Michigan. Using the motto "Honest value for an honest dollar," Carhartt worked with local railroad workers to design the perfect overall bib. Within two decades, the company's operations expanded to eight other cities, including one in world industry capital Liverpool and two in Canada.

Despite going through a period of downsizing during the Great Depression, the brand was able to rebound by capitalizing on America's efforts to rebuild after a devastating war and economic crash. The company's campaigns to redesign rugged clothing for the next generation of Americans managed to put it at the forefront of mass-produced workwear through America's post-World War II expansion.

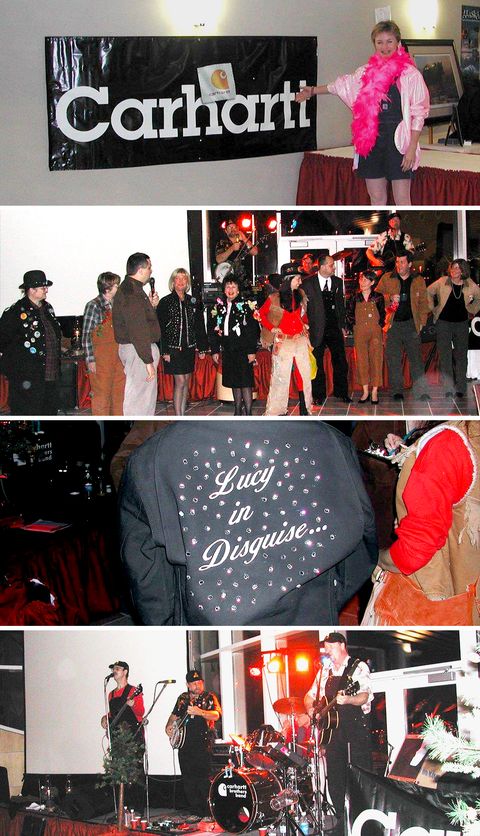

No place is more emblematic of Carhartt's working class golden age than Alaska, a state where love of the brand runs so deep you'd think it was invented there. Each year in the city of Talkeetna, residents dress up in their finest shades of brown, brown, and more brown for the "Carhartt Ball." The Alaska State Fair even hosts a Carhartt fashion show.

Both the creation of the Trans-Alaskan Pipeline and an economic boom resulting from state and private spending on construction and infrastructure caused the state's working-class economy to swell in the late 20th Century. By 1990, the population would grow to over 540,000 people. And thanks to the savvy marketing efforts of Doug Tweedie, the company's sales representative in Alaska between 1977 and 2008, Carhartt was able to ride this growth to become the most popular workwear in the state. (Tweedie worked extensively with independent stores, which, in the '70s, were the backbone of the relatively isolated local economy.)

"They were all brown duck," says Tweedie."You had three color choices — brown, brown, and brown. When they came out with black that got everyone excited again."

Once consumers realized that Carhartt's products lasted twice as long as other outdoor apparel on the market, the brand's reputation caught on despite its premium prices within the category. Tweedie even managed to get Nordstrom in Alaska to carry the brand, though this was long before Carhartt's high fashion days.

In 2001, the state laid the claim to the largest per-capita Carhartt sales in the world. Impressive, yes. But it was the end of an era. Alaska was the brand's last grab at the kind of growth that was still reliant one type of customer: the largely white working class. And that working class was changing. Two recessions in the early '80s paired with a shift to service-based goods had already resulted in the beginning of the decline of the labor economy. The old model was no longer relevant.

As chance would have it, however, a new coalition of customers had begun to gravitate toward Carhartt. In the 1980s, the brand noticed its jackets had become increasingly popular with urban drug dealers. What seemed like an unusual pairing sparked a new era: one in which the company radically expanded its idea of who the working class was, long before politicians were to come to terms with the reality.

"They needed to keep warm and they needed to carry a lot of stuff," Steven J. Rapiel, the New York City salesman for Carhartt told the New York Times in 1992. "Then the kids saw these guys on the street, and it became the hip thing to wear."

The trend had become so embedded in street culture that by 1990, the hip-hop label Tommy Boy Records gave out 800 of the jackets, embroidered with the company logo, to influential "tastemakers." The brand was seen on rappers like Tupac and Dre. (In fact, the promotion was so successful that Tommy Boy started its own clothing line.)

The street popularity also inspired German denim entrepreneur Edwin Faeh to strike up a licensing deal with the company in order to bring a more streetwear version of the product to Europe in 1994 with Carhartt Work in Progress. Though the brand still riffs on the same kind of jackets spotted on American oil workers and farmers, in Europe WIP became the uniform for skateboarders, hip-hop heads, and disaffected youth at riots and protests.

"I've always said that Carhartt didn't choose the culture, the culture chose the brand," Michel Lebugle, co-editor of the brand's history, Carhartt WIP Archives, told Dazed in 2016.

"Even if you aren't a welder or a miner you might like that rugged, 'out West on a horse' look," says former Carhartt rep Tweedie. "There have been many famous designers who have chased that kinds of look. We've just happened to come by it naturally."

The brand's fashion appeal has spread stateside in the past decade. WIP opened its first store in SoHo in 201, and now fashionable New Yorkers who have probably never seen a tractor supply store in their life browse through neat racks of the brand's designer line. (While most Carhartt jackets run below $100, WIP jackets of similar thickness run over $170.) The silhouettes of the duck jacket's high-end counterpart are sleeker, but the design is unmistakably related. It's a playbook also used by legacy brands such as Nike and Levi's, which manage to appeal to the Marshall's and Madison Avenue crowds alike.

"Carhartt is one of the few brands with a second brand, a fusion brand, that is looked at as a whole. I don't look at WIP individually, I see the message as a whole," says Brian Trunzo, Senior Menswear Trend Forecaster at WGSN. "Carhartt represents everybody. It represents the right and the left. It represents the fashion folks and the non-fashion folks. It's a brand folks can rally around. It comes down to its authenticity. Everything they do is real."

As an arm of experimentation safely padded from the core of the brand, WIP helped usher Carhartt into a new era. Long gone are the days when the company only advertised its wares in magazines like Popular Mechanics and American Cowboy with slogans likes "As Rugged As The Men Who Wear Them." The company is now a mishmash of Jason Momoa's curious surfer vibes, hunting as a form of family legacy, and even a lifestyle blog for women who prefer to craft their donuts in suspenders. Instead of just three shades of brown, Carhartt now sells products for women and children, and even produces medical scrubs (an obvious run at competitor Dickies).

What's most striking is that none of this happened because of anxiety about the future. You won't find any United Colors of Benetton-style ads from Carhartt in the '90s. Even now, the parent company's website clings to the imagery of a white masculinity that's not exactly in line with modern social and economic realities. And when asked about a subculture's affinity for the brand, the company's line for the past nearly three decades has been a big shrug. Carhartt couldn't tell you how it's marketed to such a diverse group because it hasn't. The company has followed working class America for 128 years and this is just where it wound up.

"When you have such a loyal passionate base, you want to make sure that's something you consider and you respect. And what we focus on are the commonalities," says Brian Bennett, vice president of creative at Carhartt.

If you wanted to boil the brand's secret into a business strategy, the closest you might get is its commitment to in-house marketing, a rare thing for a company of its size. Its ads feature actual consumers, giving the advertising team unparalleled access into the minds of the people who actually buy their products. To shoot its spring 2018 campaign, for example, the team will be making its way from the ranches of Southwest Texas back to Detroit, where the brand has caught on in local artisanal food culture.

Even the company's partnership with Aquaman star Jason Momoa, who has been directing ads for the company since 2015, has a humble beginning. The star, who still owns the same Carhartt pants he bought when he was 19 years old, called Bennett relentlessly asking for a meeting. It wasn't until the company's senior vice president of marketing, Tony Ambroza, told Bennett that he was a fan of Game of Thrones that Bennett agreed to get drinks with Momoa in Detroit, a decision that sparked a three-year and running creative relationship and friendship.

"He's a real sweetheart. He's an artist at heart and family man. He has a real Carhartt work ethic as an actor and a director," says Bennett of Momoa.

Celebrity or rancher, what Carhartt's customer-focused advertising has taught the company is that regardless of where consumers buy their jackets or what they know about the brand's diversified offerings, their mentalities are the same.

"What we've found is an incredible passion and respect to create and do things," says Bennett. "I'm always really inspired by how incredibly different these people are—but they all really believe in hard work."

It's the kind of authenticity that almost seems cheesy, but it's something that's stuck with the brand even throughout its expansion under current CEO Mark Valade. (Valade, who is the son of heiress Gretchen Valade, is the fifth generation of family leadership in the company).

In its native Michigan, Carhartt has been a strong champion of urban renewal. The company has its headquarters in Dearborn, and is currently working on creating 215 more jobs in the state by 2018. Some of these jobs, including designers, will bolster Detroit's growing, young urban workforce. Downtown Detroit now features the flagship Carhartt store. Not only does the company sponsor community skilled trades workshops and work-training nonprofits like Helmets to Hardhats,the Valade family sponsors the Detroit Jazz Festival and is a patron of a number of nonprofits, including the Detroit Historical Society. When Carhartt says it values the local farm-to-table chef as much as the rancher producing his beef, it means it.

And the payoff is clear. America has lost over 5 million manufacturing jobs since 2000, more than a 25 percent decrease since 1980. But Carhartt's sales are stronger than ever. Ambroza tells Esquire the company is in a "growth period" and that sales are "well over the $500 million mark." In a time when many physical retail stores are shuttering their doors and focusing on e-commerce, Carhartt is expanding its brick and mortar presence.

"I think a lot of people want to put a different point of views on things today, but what we continue to see in our community [that] if you aren't in a 9-5 job with hard work, you can still hold those values," says Ambroza."Maybe you're the first generation to move into an office job, but you grew up with those values. They still spend their weekends camping or building and they don't take the easy road. It's part of their identity."

Don't believe it? Look at Pinterest, says Bennett, and the number of women building their own bookshelves. It might seem odd to think of Carhartt's customer existing somewhere between pinned wedding dresses and diet recipes, but to the brand it's a sign that America's blue collar is alive and well.

"We may say the blue collar world is shrinking, but the blue collar mentality is not," says Bennett. "Whatever your job is, we see people really yearning to get back to a DIY lifestyle. We're happy to celebrate that lifestyle with them"

Both Ambroza and Bennett pointed to the "fifth generation" consumer as the new core of the company's business. Those who maybe work an office job but grew up with parents who didn't. People like trend forecaster Trunzo, for instance, who remembers his butcher father's love of the classic tan jacket alongside its appearances in French cinema.

That isn't to say upholding a 128-year history comes without its challenges. The brand's heritage makes for a great advertising campaign, but it also draws scrutiny.

"Lately we've noticed a lot more interest in where our 127-year old family-owned business is based and where we make our products," Carhartt commented just months ago on a nearly five-year-old ad.

The 2012 commercial for the company, titled "Made By Hand," featured its four American factories, which have outlasted the hundreds of American textile mills shuttered by 2000. And according to the comment left by the Carhartt on the ad, in 2015 alone, the company purchased 19.5 million pounds of cotton from Georgia, 32 million buttons from Kentucky, and 1 million drawcords from Rhode Island.

Ambroza says the ad was created in response to the same questions raised years ago. Because consumers hang onto their items so long, it can come as a shock when they find certain items are no longer made in the USA. Carhartt moved a large portion of its production to Mexico in 1997, and it's hardly the only "All American" brand to do so. According to the American Apparel and Footwear Association, 2.5 percent of the clothing bought in America in 2012 was made domestically, compared to 56.2 percent in 1991. In due part to NAFTA and other loosened trade restrictions, the U.S. lost nearly a million textile manufacturing jobs between 1994 and 2005.

But with the exception of a few purists, most customers don't put their purchases where their politics are when it comes to a commitment to American manufacturing. In January, market research firm NPD group found that 80 percent of consumers said it was important to "some degree" that products they purchase be made in the USA, but only 23 percent were willing to pay more "all or most" of the time. A 2013 New York Times poll found that less than 50 percent of Americans were willing to pay a premium of even $5-20 more for a domestically manufactured product. For context, the price of Levi's made in America starts at around $170 and goes up to around $270—two to three times the price of an imported pair. If the source of production was the only marker of Americanness, most large-scale legacy brands accessible to the working-class price range would be out of the running. Carhartt's U.S.-made prices are comparable to its imported products, though the line is significantly smaller.

And the company doesn't shy away from talking about its Mexican manufacturing or sweep it under the rug. "We are very proud of all of our employees around the world," says Ambroza.

And though Carhartt has yet to pull any semi-political stunts with its advertising (think 84 Lumber and Budweiser at Super Bowl LI), everything it does echoes its core values. Yes, the company's refrain of "hard work" as if it were somehow a value that transcends the very real and painful divisions in modern America might seem like a copout. But at the end of the day, Carhartt is a business. And if marketing the same history for 128 years allows it to grow, why rock the boat?

"If you are a brand that is making clothing and that's all you're doing, you're not obligated to wear your political obligation on your sleeve," says Trunzo. "The product is enough."

And now couldn't be a better time for Carhartt to lean into its history, the task that Ambroza and Bennett have set for themselves. The 2016 election and its "Make America Great" again rhetoric brought zealotry around saving American manufacturing back into the forefront of conversation. "Buy American and Hire American," an executive order, signed by the president in April, would promise protections for American-made goods and reform the H-1B visa program for skilled workers to increase the hiring of Americans. The White House's rhetoric invoked a familiar image, one of bearded white men wielding blowtorches and machinery. It's the kind of working class- first politics that has gained the support of the Teamsters and United Auto Workers. And it's the exact imagery that, despite its 128-year evolution, still dominates Carhartt's advertising.

Fortunately for the company, a renewed political interest in the working class has translated to a renewed sartorial interest as well. related. For instance, the brand recently scored a collaboration with Vetements, a design collective known for other high-low mashups like its Champion tracksuit, which will cost you approximately 100 times the price of seemingly similar garb at Walmart.

"I think that all heritage workwear brands are under the microscope right now, and we're re-entering a period of workwear appreciation on the catwalk and street," says Trunzo. "We're going to embark on a period where this new wave of workwear is going to meet the mainstream."

But it's this very intersection of optics and politics that now opposes Carhartt's vision of a new generation of blue collar-minded consumers. For decades, Carhartt has quietly thrived in spite of a shrinking working class. Now, debates over the working man have been brought to the forefront national discourse, both picking him apart and promising him a new golden age. The question is if the diverse coalition Carhartt has built along the way can survive the ride.

When you speak to Carhartt wearers from all walks of life, the camaraderie they feel when they see another brown jacket is real. But it's also deeply routed in the idea that a diversity of buyers can see themselves in America's hardworking and industrious roots. Now, rhetoric skews towards limiting that definition, focusing on a disgruntled white and often rural working class. As Carhartt's history has shown, political movements have co-opted the brand before—whether it was rebellious European youth or Alaskan politicians—but with little threat to the brand itself. Are things different now?

We live in an age where, for every picture of Chance the Rapper and his daughter sporting matching Carhartt overalls, there's a feature describing a neo-Nazi or everyman Trump voter wearing the jacket. Carhartt certainly can't control those who co-opt it for their own causes, but it's stood firm on one principle: Carhartt is for everybody. It's the kind of inclusive vision of the working class you would hope that America would have in 2017—the one that we need. We should all cross our fingers that politics don't take it away.

"We stand for hard work. We've stood for that since 1889 when [Hamilton Carhartt] was focused on making a better product for workers that didn't get a better product," says Ambroza. "Times will come and go, times will change, but we've consistently stood with the working class."