Keeping Track of Every Book You’ve Ever Read

A New York Times editor on the coffee-stained list she’s kept for almost three decades

By Heart is a series in which authors share and discuss their all-time favorite passages in literature. See entries from Colum McCann, George Saunders, Emma Donoghue, Michael Chabon, and more.

When she was 17, The New York Times Book Review editor Pamela Paul decided to start writing in a journal. It wouldn’t be any of the standard things, she thought—not a diaristic retelling of people and events, or a writer’s notebook for drafting and reflection. Her project, instead, would be a “book of books” (or “Bob, for short): an ongoing list of what she’s read, each title numbered sequentially with the author’s name, starting with Franz Kafka’s The Trial. Almost three decades later, she’s still at it.

In her new memoir, My Life With Bob, Paul looks back at her life in reading, with defining episodes framed by entries from The Master and Margarita to The Hunger Games. Throughout, Paul celebrates the power books have to transport us, to lift us almost bodily into distant lands and the dilemmas of other people. At the same time, she explores the way books also draw us inward, becoming repositories for our memories and private wishes. In a conversation for this series, Paul explained how some entries in her book of books have the power to viscerally conjure up the past, like Proust’s famous madeleine.

Paul describes her reading habit like a hunger than can’t be satiated, that grows, instead, with each new morsel she devours. The book seems haunted by this realization, the plain fact that no one can read it all—no matter how many built-in shelves she hammers up, no matter how their shelves sag with weight. As Paul puts it: “The more you read, the more you realize you haven’t read; the more you yearn to read more, the more you understand that you have, in fact, read nothing.” We discussed how she’s dealt with this anxiety not only in her own life but as the editor of the Book Review, where decisions about what to feature (and not) help shape the tastes of the broader public—the things we will or won’t get to in our own limited time as readers.

In addition to overseeing the Times’s books coverage, Pamela Paul is the author of Parenting, Inc., Pornified, The Starter Marriage and the Future of Matrimony, and By the Book, a collection of her interviews with authors. She spoke to me by phone.

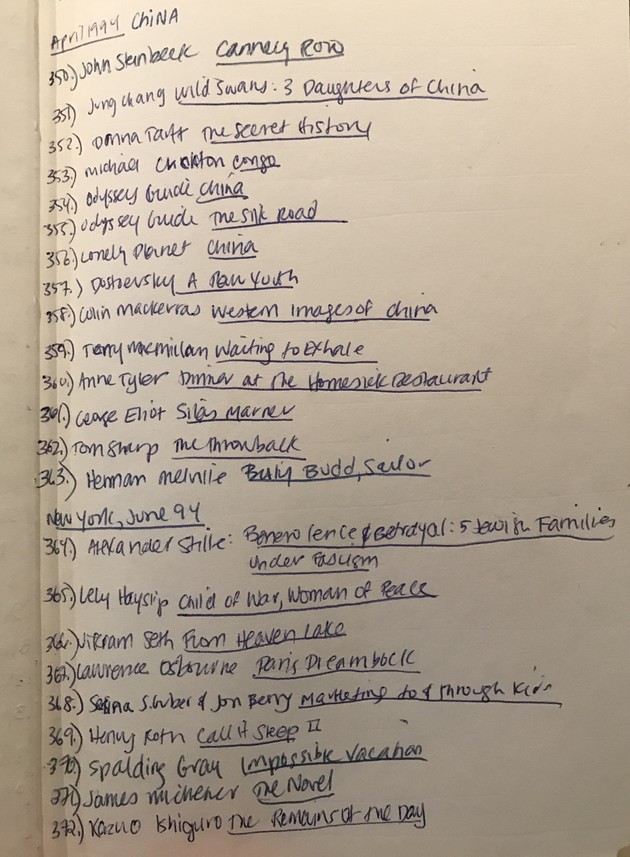

Pamela Paul: Since I was 17 years old, I’ve been keeping a journal of all the books I’ve read. I call it Bob, which stands for Book of Books. It’s a charcoal gray, unadorned, blank book that I bought in 1988 before Moleskines and bespoke journals were available—all they had, essentially, at the corner stationery store in my town. It’s not pretty. I’ve spilled coffee on it. It’s incredibly frayed. Recently, it’s started to come apart at the spine, as if Bob knew I was writing about it and took offense.

I’m only allowed to write in my Bob when I’ve finished a book, and not a moment before. I generally finish books, but if I don’t, I have to write a little empty square next to the title to show it’s incomplete. That’s it. There’s no book review. I don’t write thumbs up or thumbs down, or have a star system. I didn’t even number the entries until I was into the several hundreds. It truly is a list. But, of course, it has become more than that.

Like most bookish, word-oriented young women, I did try to keep diaries growing up. Those diaries were really kind of awful. They were angsty accounts of things that had upset me—so depressing to read, and not particularly well-written. Who wants to think about that time when a friend said she couldn’t sleep over, then slept at someone else’s house instead? That’s no fun, nor are the unrequited crushes of adolescence. But what I did want to remember—what I found I much preferred—was to remember the books I was reading while those things happened.

Looking back through my Book of Books, I don’t always remember the books themselves in great detail. And yet something about this simple list helps me recall certain periods of my life with such clarity. Whether the emotions are tied to what happened in a book, or what I was going through at the time, somehow everything just comes rushing back.

To give an extreme example: In 1994, I was traveling in China, alone, on a budget of $15 a day. Even in 1994, this was not a lot of money. This was before the internet, and before cell phones. I was completely out of touch with everyone and everything that I knew.

I spent a night in a yurt on an oasis in the Chinese desert. It was April, and it was extremely cold. April is summer in Thailand, where I’d been living before the trip, and I was so unfettered from everything that I assumed it was summer in China, too. But it was not summer in China, in the northwest, in a desert oasis in April. It was freezing, and I was staying in a sheepskin yurt in the mountains.

I was staying with three men—one was Kazakh, one was a former East German border guard, and one was Korean—none of whom spoke English, but who could speak a little bit of Mandarin to each other. There was nothing for me to eat, because I’m a vegetarian, and everything was cooked in yak lard. I couldn’t even make Nescafe, which I was carrying in packets around China, because the water was boiled with the yak butter. I did not want to make my Nescafe with yak water. So I didn’t have any caffeine. I was freezing in cotton fisherman pants and a light plastic windbreaker. And I had no one to talk to.

That night in the yurt, I finished reading Jung Chang’s memoir Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China. It’s a memoir of three generations in her family: her grandmother, who was the concubine to a Manchurian warlord; her mother, who was a high-up official in the Communist Party; and then Chang herself, who was a Red Guard as an adolescent, before going on to become an academic in London. The story was about these incredibly tragic and difficult lives, and as I read I started to feel like what I was doing was really hard, too. You know, being in a yurt with nothing to eat, and everything around cooked in yak lard.

But things got worse. There was a blizzard in the morning, and we were snowed in. We decided to leave the yurt, and then had to walk 14 miles in the snow to get to the closest village. As we walked, I thought about Wild Swans and told myself: “What you’re doing is not hard, you big baby. You’re nothing but a big baby. Think about what these women went through, these terrible circumstances. And here you are, poor thing. You didn’t have any Nescafe! You don’t know what it means to be deprived.”

When we finally arrived, my shoes were covered in blood. I had two pairs of socks on, and they were covered in blood, too. There’s more to this story, which I recount in the book. I basically made this sort of radical decision to try to limit what I ate for the rest of my trip—just to experience deprivation, just to try to acquaint myself better with suffering. And you know what? It was really hard. I lasted only 4 weeks. When I look back at that entry in the Book of Books, all of that comes back. The recall is so intense that I never need to look at my photographs from that time. I can just look at this entry, number 351 in my book, and remember all of it. All those feelings. What it felt like charging through the snow.

Looking back at my Book of Books tells me not only what I read and when, but also something about my decision-making process as I moved from book to book. Some of those decisions were very self-conscious, intellectual decisions. Some were more gut-level. Either way, I love the way those early entries show a young person’s curiosity at work: What did I want to know then? What did I feel I needed? Where did I want to be?

I’m a very slow reader, which is my great failing in life. I think if I could change one thing about myself, it would be to be a faster reader. At the Book Review, my colleagues and I will talk about what we’re reading, and it’s a lot of fun, but at the same time, there’s this constant thread that winds its way through our conversations: All of us have gaps in our reading. Books, authors, whole genres that we’ve really never read.

It’s depressing to contemplate the fact that I won’t get to read everything I want to read. So depressing that I sometimes slip into a kind of delusional thinking: “Well, if I read an extra hour every day, maybe I will get to read it all.” Which, of course, is nonsense.

A similar dilemma is also reflected in my work at the Book Review, where we have to decide what to feature in our pages. This is exciting, but also daunting: We go in knowing there are many more worthy books than we have the space, or the resources, to cover.

When I first started at the Book Review, I was the children’s books editor. We had the only full-time children's books editor in the country, and that person had to read all the children’s books as they came out. When I got there, I realized that my predecessor had only two pages in every month. I went to Sam Tanenhaus, the editor of the Book Review at the time, and said, “It’s not enough.” I asked him to make it three pages every month, and to add an extra issue once a year with 10 pages. But even that was not enough. So I wrote a weekly online book review in addition, just to try to cover all the books.

Even expanding coverage in that way, I quickly realized I couldn’t cover all the books. There were still so many children’s books. There were very deserving picture books, novels, YA books, and non-fiction that weren’t getting in. I called my predecessor, Julie Just, who’d been the children’s book editor before me. I was frantic. “Julie,” I said. “I can’t get all the books in."

She said, “No one expects you to get them all in. There’s no way to get them all in. Everyone knows you can’t even cover all the important books, or all the good books. So stop worrying about it.” That was a tremendous relief, even though I felt badly about it. I still do.

At the same time, I know that we’re ultimately not there to serve the authors and the publishers and the illustrators. It’s easy to forget that we’re not out there trying to help all the writers, even though we love them, or everyone else who works so hard to bring these books into the world. Ultimately, that’s not our job.

The people we’re trying to serve are readers of The New York Times. I know—because I’m one of them—that readers of the Times have a limited amount of time to read, so they’re looking to us to do an essential triage.

When you turn it around that way, it becomes clear: What we’re really doing here is providing a service by narrowing it down. We’re not covering everything that’s worthy of coverage, but we are covering books in a much more comprehensive way than anyone in this country. And the fact that it isn’t such a large number of books is, in itself, helpful to our readers. That makes me feel better.

A book review, of course, is a piece of writing in itself—it’s a form you can do well or not do well. Ideally, it should be entertaining and enlightening to read because, ultimately, you want people to read the review, even if they don’t read the book. It’s important that people can appreciate a review on its own terms.

A good review should be thoughtful, should be provocative, and should provide a sense that the reviewer has really engaged with the work. It’s not supposed to be a cold-blooded assessment of what’s in the book. You should feel there’s something at stake. There should be opinion in it, too. And there should be an example of the writing. It’s amazing to me that some people will hand in a book review and never quote from the book. If you’re describing a book, what better way to show it than through the text itself?

Often it’s easier to talk about what a book review should not be. A book review should not be a book report. And a book review should not be a platform that merely forwards an argument. It’s not an op-ed. Sometimes the writer will use a book on a topic as an excuse to pontificate or make some kind of argument about that subject, as opposed to sticking to the book at hand, or sometimes a book reviewer will review the book that they wish that that author had written, rather than the one that the author had written.

A book review should not leave you guessing as to what the reviewer thought of the book. Sometimes a reviewer will hand something in, and you don’t really know what they thought of the book. But in their email, the reviewer will say “Wow, I loved that book.” Well, why not say that in the review? The reader should come away knowing what an author did well, what an author didn’t do as well, and knowing what is interesting and important and new about this book—or not.

For me, reading books is like trying on a different kind of life, a different way of thinking or seeing the world. Anytime you pick up a book, you dive into a different lifetime for a period, whether it’s fiction or nonfiction. You read Emile Zola’s Germinal and you know what it’s like to be a coalminer in 19th century France. Or you read The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead, and you have a sense of what it might have been like to have been a slave in America. You read Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy and you get to experience what it was like to have been a spy. Books enable you to try on a different life, one very different from your own, that you have no other way of living.

After all, you might be able to quit being a psychotherapist in Denver and become a massage therapist in Asheville, North Carolina, but you cannot go back to 19th-century France to be a coal miner. Not unless you read this book. A book enables you to live that many more lifetimes, to try out that many more lives and ways of seeing the world. It’s like having your own time machine. What could be more magical than that?