In a territory of some 1.3 million hectares live 20,000 people: the Wampis. There are no roads and the two main rivers, the Santiago and the Morona, provide the only access to trade and the outside world.

Lima, the capital of Peru, lies on the other side of the Andes, 1,500km away.

Wampis like to say that the forest is their supermarket. The rivers are key to daily life as a source of clean water and fish and there are no problems with food security in the region. Amazonian forests are nicknamed “the lungs of the planet” for their capacity for turning carbon dioxide into oxygen, mitigating climate change.

Wampis used to live dispersed in the forest. Only with the arrival of missionaries and schools in the 1960s did they move to form communities around the school buildings.

- Left, children play football under torrential rain in Soledad, on the Santiago river. Right, a man takes a break from working the land to drink masato, made of fermented yucca

Chakras are ancestral plots of land belonging to the community but temporarily used by individual families. During the day a family usually spends time cultivating its chakra. Common harvests include banana and yucca, which make up the core of the Wampis’ diet. Little cacao plantations are becoming common, allowing people to sell some of their crop. Although money is not essential, it is useful to buy petrol for transport, clothes, solar panels and, increasingly, for the higher education of children.

- Land destroyed by gold mining along the waterway of the Quebrada Pastacillo

Illegal gold mining is very prevalent in the region of the Santiago river, where an estimated 20-120 grammes can be harvested in a day, worth between $600-$3,000 (£465-£2,320), a lot of money in this poor area. Aside from the destructive impact on the landscape, gold mining commonly involves the use of mercury, which leeches into the water and the food chain.

- Illegal miners extract gold from sediment on the Marañón river

Rogelio Padilla, below, shows where his family chakra used to be. “We cultivated this land since the time of my grandfather,” he says. “But when illegal miners arrived they behaved as if the land was belonging to them.” When a forest that could sustain generations is destroyed, the loss is impossible to quantify.

- Rogelio Padilla indicates the location of his family’s old land

The only road access to the Santiago river in this region is La Poza, a booming frontier town. Here indigenous people, settlers and miners can trade. The town has a thriving nightlife where miners can easily spend their wages. HIV and prostitution are emerging problems.

Michael Wampankito Ungum is an MP in the Wampis government and works, as many others from its community, on cleaning up the oil which has spilled out into the forest from the North Peruvian Pipeline. The pipeline, which is long overdue to be replaced, connects the Tigre region, in north-eastern Peru, to the coast. Leaks and spills are frequent.

- Michael Wampankito Ungum is working on containing the latest oil spill in the Mayuriaga community

- People at work on the cleanup of the Mayuriaga oil spill, in 2016

The latest spill, in 2016, affected 30km of tributaries before seeping into the main river Morona, and affecting communities living downstream. The cleanup operation, still ongoing, is involving almost 500 people, and will take at least a year. Every piece of soil and vegetation which has been in contact with the crude oil has to be destroyed.

The oil company involved is now distributing bottled water and food to the people affected by the spillage. The Mayuriaga community is in the process of asking for compensation for the contamination of territory fundamental to its survival.

But more change is on the cards for the Wampis. A dam project has been looming on the upper Marañón. A series of 20 dams are already in advanced stages of planning. It has been estimated that the biggest, on the Manseriche, could flood 5,470 square km.

- A canoe navigates up the Marañón river towards the perilous pongo – rapids – of Manseriche. In Quechua, Manseriche means ‘the frightening gorge’

The indigenous people still remember the loss of life in 2009 when they rose up to demonstrate against outsiders accessing and violating their lands, under a set of laws facilitating access to their lands by the extractive industries.

Wampis and Awahun people marched to Bagua, blocking the main road. In the clashes that followed, at least 34 people – 24 policemen and at least 10 civilians – died.

“[After the deaths], relations between the Peruvian government and the indigenous organisations reached a low point,” says Andrés Noningo, member of the Council of the Elders of the Wampis nation. “When the Peruvian government speaks about development, they mean the exploitation of our resources: gold, oil, wood. This threatens our livelihoods. That’s why we formed our autonomous government, to ensure a good life also for future generations.”

- Left, crosses at the Pumping Station 6, on the North Peruvian Pipeline, to remember policemen killed during the events of 2009 in Bagua. Right, Andrés Noningo, 62, member of the Council of the Elders of the Wampis nation

Noningo was among the representatives of more than 100 indigenous communities who in 2015 gathered in the small village of Soledad to announce the formation of the autonomous territorial government of the Wampis nation, the first of its kind in the Amazon, with its own constitution and parliament. The delegates came on foot and by boat, some taking four days to reach Soledad.

“We will still be Peruvian citizens,” he says, “but now we have our own government responsible for our own territory. This will enable us to protect ourselves from companies and politicians, who only are able to see gold and oil in our rivers and forests.”

- Female leaders and members of parliament on their way to the assembly of the Wampis nation

Wampis were inspired to create the new government by the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and were driven by the multiple threats to their environment.

- Wrays Pérez, 55, president of the Wampis government, asks new members to take the oath

The constitution has 40 pages with detailed provisions on rights and duties of the government and the management of the territory and culture.

The communities have some land rights recognised by Peruvian legislation, including foraging and hunting.

- Members of different communities of the Wampis nation map the traditional use of territory along the Morona river

At school here, young people are taught in Spanish and in the Wampis language, making the classroom a strong force of cultural homogenisation. Higher education is possible only by leaving home and travelling to cities.

Kefren Graña, 45, a former teacher, is the minister of education of the Wampis nation, and promotes the use of hallucinogenic plants fundamental to connecting with nature: “Ayahuasca, tobacco and toé are our university.”

- Clockwise from top left: children during a primary class in Soledad; Kefren Graña, 45, a former teacher amd the minister of education, who promotes the use of hallucinogenic plants; teenagers drinking and vomiting ayahuasca; Jorge Zukanká, 47, collects ayahuasca vine for a ritual

Teenagers are encouraged to seek visions. Incited by their families, they will drink 20 or more litres of ayahuasca liquid and often report hearing secret messages from an ancestral spirit taking the form of a boa, a jaguar or a hummingbird. Not everyone sees visions immediately and the whole process might have to be repeated several times. These predictions of the future will lead young people for the rest of their lives.

Such visions are essential to the culture of the Wampis people.

“Our ancestor noticed that the animals speak and even the earth moves and they asked where do these animals come from?” says Andrés Noningo. “What is the origin of the air we breathe? Who looks after the trees? What is the origin of life? To seek wisdom our visionaries would spend up to three months in the forest. They taught us that animals and trees are people just like us and have their guardians that protect them.

“This is why our ancestors were able to teach us where the animals live, where they reproduce, which lands are fertile and which are un-productive, where we should make a farm and how to hunt with respect, using our sacred songs that ensure we treat all living beings with dignity.”

- A man builds a trap for ground birds, a construction that can take up to two days and is accompanied by traditional songs

At primary school, children learn about traditional fishing, a method still widely used today. The Barbasco, a root, is smashed and mixed with water to poison fishes, which are then finished off with machetes and harpoons.

- Primary school children during a class about traditional fishing

The Wampis’ desire to protect their way of life has been strengthened by what has happened to the Shuar people in neighbouring Ecuador, people of the same ethnic group as the Wampis.

- Left, Shuar young people from the Ecuadorian side of the Santiago river rehearse for a traditional dance during an Ecuador-Peru bi-national meeting. Right, Shar girls in Ecuador

A major road accelerated the loss of Shuar identity: many people have forgot their native languages, and cattle farming and logging are more widespread.

One of the key demands of the Wampis government is the power to patrol its territory to guarantee a quicker official intervention on illegal mining and logging than that by Peruvian state agencies. The Peruvian government is engaged in a much-publicised fight against illegal miners, searching and destroying their equipment, but it seems to be ineffective.

In July last year the Wampis invaded the site of an illegal mine on the Santiago river to protest against the activities there. Miners, who had been tipped off, hid the machines and suspended their work for a few days.

As expected, once the protestors left, the illegal gold miners returned to their activities at the site.

The Wampis government is now urging allied politicians in the National Congress of Peru to push through legislation that would officially recognise the status of its nation.

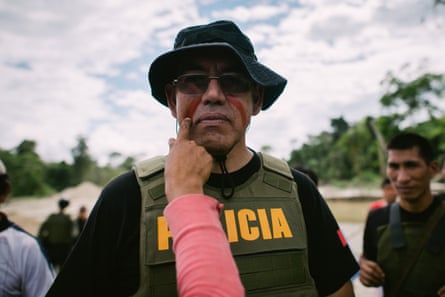

- Left, graffiti in Santa Maria de Nieva remembering convention 169 of the International Labour Organization, the first international law recognising indigenous peoples’ land ownership rights. Right, the chief of the local police receives his warrior face painting, as a sign he is an ally in the fight against illegal gold mining

In May, in the Peruvian capital Lima, all the documentation – legal and anthropological studies, maps and minutes of meetings – was handed over to inform the Peruvian state officially of the existence of the Wampis nation, setting out that its people exercise the right to autonomy and self-governance within their ancestral territory.

The Wampis underline that self-determination doesn’t mean separatism – they remain Peruvians.

- Children sleep during the farewell party of the assembly of the Wampis nation