Veteran cavers Peter and Ann Bosted were cruising around their hometown of Hawaiian Ocean View, on Hawaii’s Big Island, a few years ago when Ann spotted a small hole off the side of the road.

It was no more than three feet wide—just big and inviting enough for the couple to pull their car over and try to slink into.

“We had a couple hours to kill,” Peter told me, “so we started surveying, and we found a side passage that turned out to be a lot more mazy than we expected.” Back home, Peter marked the puka, or cave entrance, on a digital map and planned to return later—with the landowner’s permission—to see where the opening might lead.

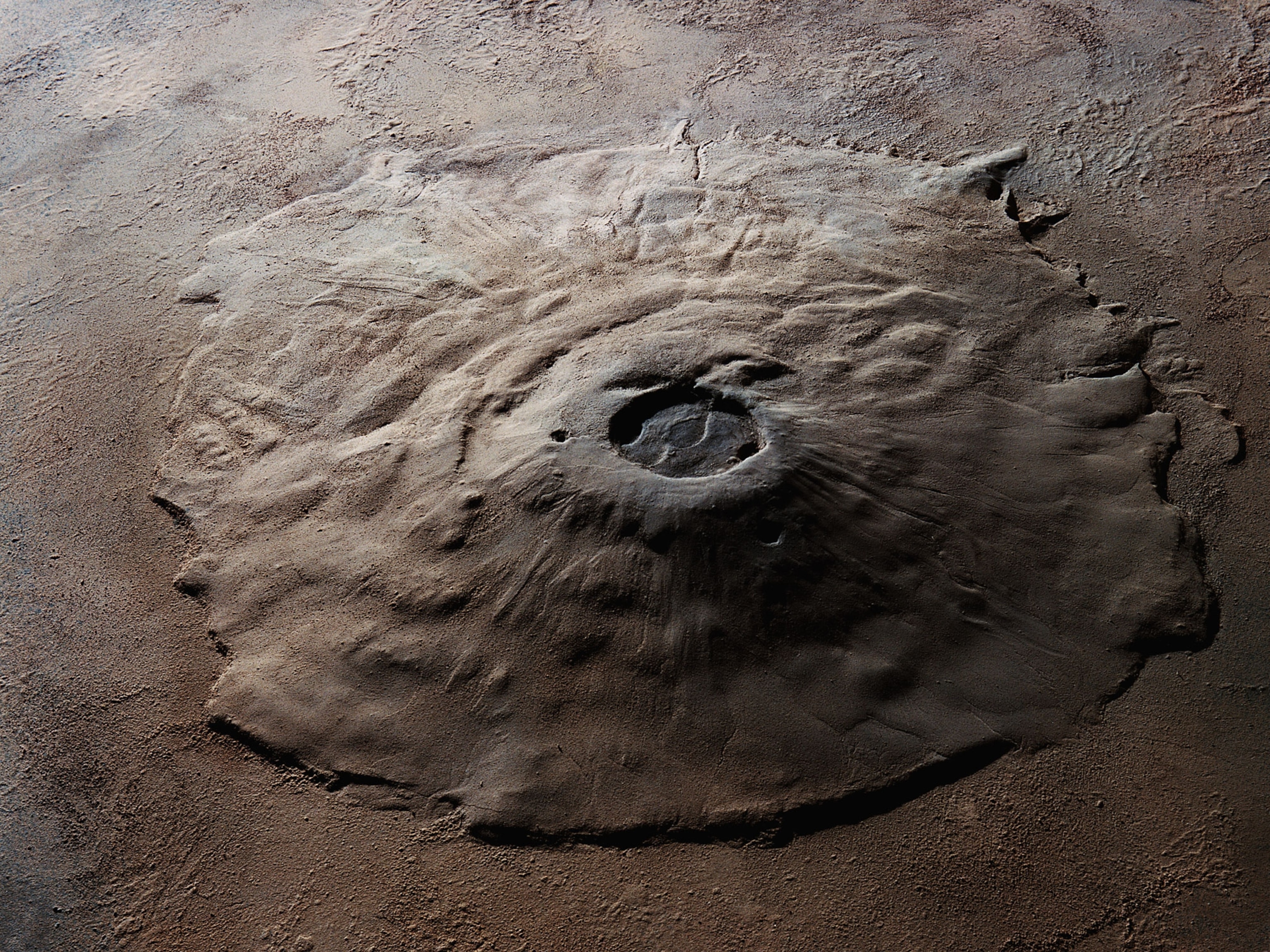

From outer space, the town of Hawaiian Ocean View looks like a thatched mat of asphalt draped over the side of Mauna Loa volcano. The 102-square-mile grid of crisscrossing streets and vacant lots is nearly twice the size of Washington, D.C., yet is home to fewer than 4,500 residents. You might think that only a pathological optimist would choose to build a house on the parched slope of an active volcano, but over the past two decades, Ocean View has become an international destination for cavers, who have come to explore and map the Kipuka Kanohina, a network of lava caves that course like veins 15 to 80 feet beneath the town.

There are two ways to make a cave: fast and slow. Many of the world’s most iconic caves—Carlsbad Caverns and Lechuguilla in New Mexico, Mammoth Cave in Kentucky—were carved out over millions of years, by the plodding drip and flow of acidic water through soluble limestone.

By contrast, lava caves, widely known as lava tubes, are formed in a geological instant—a year or two, sometimes weeks—by an eruption from the Earth’s crust.

Most of Hawaii’s lava tubes are formed by a type of syrupy flow called pahoehoe. As it pours down the volcano, the lava at the surface is cooled by the air and solidifies, creating an elastic, skinlike outer layer. Beneath this inflating membrane, the lava continues to ooze, eroding the ground beneath it and carving underground tunnels. Now insulated from the air, the hot lava can surge unimpeded, often for many miles. As the eruption subsides and the channels drain their last molten contents, what’s left behind is a massive, 3-D fun house of plumbing.

Probably no other place on Earth has as many accessible lava tubes as Hawaii, and probably no other town has proved such fertile terrain for their exploration as Ocean View.

In the 1990s, the Bosteds were active members of the team that mapped the 138-mile-long Lechuguilla Cave, widely regarded as one of the world’s most beautiful. Now in their 60s and semiretired—Peter is a particle physicist affiliated with the College of William and Mary—they are among a handful of experienced cavers who have become full-time residents of Ocean View. Ann has pigtails down to her waist, and Peter sports a bright Hawaiian-print shirt, a white driver’s cap, flip-flops, and a biblical-length white beard. They say they’re now doing more caving than at any other point in their lives. They reckon that some years the two of them have spent more than 200 days underground.

Peter and Ann brought me back to explore the new roadside puka they’d discovered, along with another couple, Don and Barb Coons, Illinois grain farmers and lifelong cavers who winter in Ocean View. Don, 64, was a guide at Mammoth Cave for 10 years and spent 18 winters on the legendary expeditions that helped expand the map of Chevé in Oaxaca, Mexico, the second deepest cave in North America. He’s the president of the Cave Conservancy of Hawaii, a nonprofit trust that has been buying up land in and around Ocean View to preserve the tunnels that lie beneath.

Wearing helmets, headlamps, and volleyball pads on our elbows and knees, we slither on our backs into the hole and army crawl for about a hundred yards through a previously mapped passage less than three feet tall. It has been centuries since lava flowed through this particular cave.

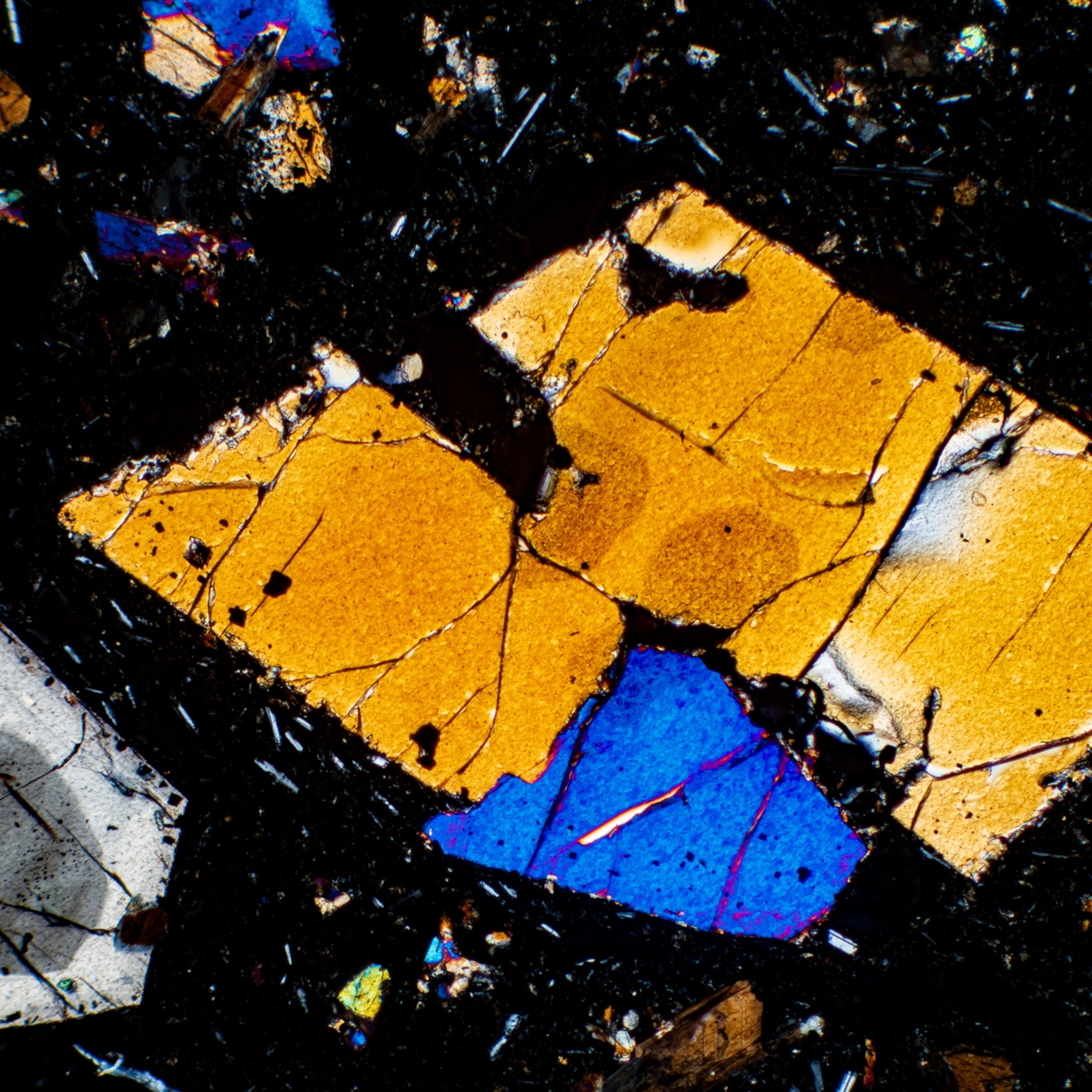

Festooned with trippy Dr. Seuss–like ornaments, the lava tubes of Hawaii seem to belong on another planet. Delicate lavacicles hang from the walls and ceilings like stalactites and take on a panoply of weird shapes, from spiky shark’s teeth to bubbly, gooey driblet spires. Long, hollow soda straws, squeezed out of the ceiling by gas while the cave was cooling, hang in thick clusters. In spots, the cave’s silvery, magnesioferrite glaze crinkles up like peeling paint. Elsewhere a thin layer of gypsum colors the walls a bright white, and mats of rock-eating bacteria excrete blue-green splotches of microbial poop.

Our army crawl ends at a junction where the ceiling dips down to less than a foot above the sharp, serrated floor. “This is our idea of fun,” Peter says drily, as we wriggle forward on our bellies into the impossibly tight crawlway, my T-shirt audibly ripping on the jagged floor. The passage is too cramped for even our helmets to squeeze through, so we take them off and shimmy forward in the dark.

For all our scrapes, bruises, and torn clothing, our compensation this morning will be 154.4 feet of fresh cave added to the map of the Kipuka Kanohina network. That may not sound like much, but it’s through days like this that the map inches toward completion at the rate of three to four miles a year. Kanohina may soon be the longest surveyed lava tube system in the world.

The cave that the Kanohina system seems poised to supplant in the record books is on the other side of the Big Island. It was likely created during a 15th-century eruption of a different volcano, Kilauea. At more than 40 miles long, Kazumura is the longest lava tube mapped to date, and also the deepest. Though its roof is never more than a few dozen yards beneath the surface, the vertical drop—from the top of the cave, midway up the volcano, down to its terminus near the coast—is 3,613 feet.

Unlike the Kanohina system, which consists of several parallel passages that interweave like the delta of a large river, Kazumura is mostly one long, gaping straight shot of a tunnel—so wide and tall (more than 60 feet) in parts that it feels as if it could be easily adapted for a subway train. Despite Kazumura’s cavernous profile, the first through trip didn’t take place until 1995, when it was completed in a two-day expedition.

“This is a national treasure, and yet there are people on this island who live right on top of the cave and don’t even know it exists,” says Harry Shick, a landowner who operates tours through a stretch of Kazumura that lies under his property.

There is, it seems, an omertà that surrounds the Big Island’s lava tubes. Most cavers and conservationists would prefer that outsiders never learn the locations of their finds. When the Bosteds offered to take me to a cave called Manu Nui that they’ve been mapping since 2003, it was on the condition that National Geographic not reveal its precise whereabouts, except to say that it was created by Hualalai, the island’s third most historically active volcano, after Mauna Loa and Kilauea.

Manu Nui is, in many respects, the jewel of the island. With an average incline of 15.7 degrees, it is one of the steepest lava tubes in Hawaii, and its features are surreal. After entering the cave through a mist-shrouded puka on private land, we head uphill to a chamber that could be a fantasy from Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory. The walls, spattered in chocolate-, peanut butter-, cherry-, and butterscotch-colored drippings, look so luscious and fudgelike that I’m almost tempted to lick them. The Bosteds are keen to ensure the unique formations aren’t disturbed by curious adventure seekers. A lavacicle is a fragile thing, and it takes only one misplaced handhold to permanently disfigure a cave. Shick has meticulously gone through several miles of Kazumura, reattaching fallen features with superglue.

“We don’t even fully understand these cave ecosystems,” says Lyman Perry, from Hawaii’s Division of Forestry and Wildlife, “so we don’t want people going into them. The reality is that if people find out about these places, they’re going to ruin them eventually.”

Even more delicate than the caves’ features are the cultural sensitivities that surround them. Many native Hawaiians consider lava tubes kapu, or sacred sites, because of their frequent use as ancient burial grounds. In Hawaiian tradition, bones contain a person’s mana, or spiritual energy, and aren’t to be unnecessarily disturbed.

Keoni Alvarez, a 31-year-old activist and filmmaker who has battled developers trying to build atop burial caves, says that whenever human remains are found inside a lava tube, they render the entire cave system, start to finish, kapu. “We believe our caves are sacred and should not be desecrated,” he tells me. The problem is that no one can know whether a particular cave was used for ancient burials until it has been explored. Many native Hawaiians categorically refuse to venture into lava caves out of respect for what they might encounter inside.

But if modern Hawaiians tend to be wary of lava tubes, their ancestors clearly used them quite a bit. Many cave openings show evidence of prehistoric habitation, complete with hearths and sleeping terraces. In war, longer lava tubes were sealed and used as “refuge caves” to hide women, children, and elders. In some cases, stone walls were built across tube entrances, leaving a passage just big enough for a single person to climb through.

A local expert estimates that one in two caves on the Big Island contains some sort of archaeological artifact. Especially on the dry, leeward side of the island, freshwater is hard to come by, and lava tubes were often the best place to find it. Deep inside Kanohina, hundreds of yards from entrances, one frequently comes across remains of kukui-nut torches and rings of rocks that once propped up gourds used to collect dripping water.

Don Coons and Peter Bosted are insistent about the difference between adventure and exploration. Adventure is what you do when you’re out for a thrill. Exploration is slow, methodical, and never for your sake alone. Every cave they explore, including this narrow, jagged section of the Kipuka Kanohina that we’re crawling through, must be meticulously surveyed and mapped using clinometers and laser range finders.

“The deep sea, outer space, and caves: Those are the only frontiers left,” says Coons, who does his exploring in a lightweight helmet with a small flashlight duct-taped to the brim. “On a workingman’s salary, you can go into an unexplored place and discover something new and be the only person in history to see it.”

Back in the roadside puka, our prone bodies pinched between the ceiling and floor, Bosted makes a disconcerting judgment call. “This seems a bit dangerous,” he says in his dry monotone. “I have to exhale in order to get through.” He announces that he’s turning around, leaving the rest of us to figure out where the cave might lead.

Seven and a half body lengths farther on, we reach a pile of breakdown rocks so heavy they can’t be budged from our prostrate position. The lead ends here for now, but the cool breeze we feel flowing over our faces can mean only one thing: There is more cave to chase on the other side.

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

Environment

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

History & Culture

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

- The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’

- Heard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followersHeard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followers

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?

Travel

- What it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in MexicoWhat it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in Mexico

- Is this small English town Yorkshire's culinary capital?Is this small English town Yorkshire's culinary capital?

- This chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new directionThis chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new direction

- Follow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood ForestFollow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood Forest