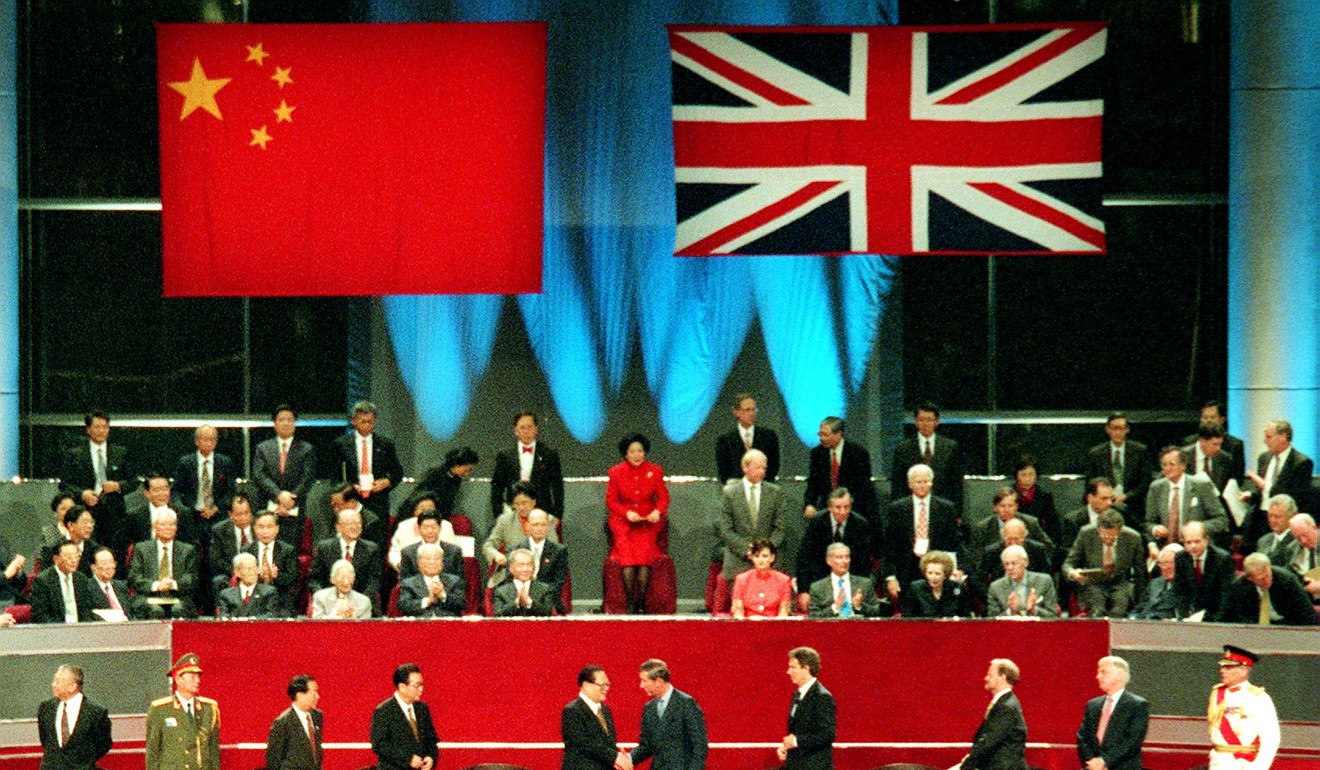

Twenty years on, is Deng Xiaoping’s ‘one country, two systems’ blueprint for Hong Kong working?

The governing formula under which Hong Kong returned to China two decades ago has largely served the city well, but there are increasing strains on the system as localism gathers pace and Beijing begins to assert its authority

Two decades into reunification with China, Hong Kong’s “one country, two systems” is an everyday reality rather than a political experiment. However, whether the historic venture has proved a success is still open to debate, and the conclusion seems to have shifted from a once resounding yes to an increasingly ambivalent verdict.

The policy has undoubtedly served the city well, as reflected by various international assessments of the post-handover situation over the years but, as we move along, there is more uncertainty.

If the first decade was marked by a change in Beijing’s hands-off policy regarding city affairs, the past decade saw an even more assertive approach. There was even talk of scrapping the “two systems” if “one country” was jeopardised, presumably stemming from calls in some quarters for the city to break away from China.

The threat to roll back on a solemn promise enshrined in the Sino-British Joint Declaration and the Basic Law, the city’s mini-constitution, was simply unthinkable in the early days.

The formula remains unchanged today, but the emphasis has shifted over the years, so much so that the meaning is also changing.

First raised by late paramount leader Deng Xiaoping as the answer to the Taiwan issue, “one country, two systems” simply meant that the way of life in the former British colony was set to remain the same for at least 50 years.

Its essence was succinctly captured in the sayings that “horse racing will continue, and the dancing parties will go on”, and “river water should not interfere with well water”. In other words, our way of life should remain the same and distinct and we should not meddle with each other’s system. It was heralded as a pragmatic framework to reunite two places separated by 150 years of ideological and institutional differences.

The separation of the “two systems” was religiously followed in the early years. Officials dispatched from the mainland refrained from speaking in public, and the People’s Liberation Army stationed here was largely invisible. Any sign of interference was taken seriously. According to University of Hong Kong surveys conducted at this time, public confidence hovered around 60 per cent.

But 20 years later, the public appears to be not so sure about the future. Those who expressed no confidence in the formula stood at 52 per cent in the second half of 2014, and the trend continued before easing late last year.

Professor Lau Siu-kai, formerly head of the Central Policy Unit, a government think tank, believes the implementation of the formula has, by and large, been a success.

“The original goal was to ensure a peaceful and smooth handover. Speaking overall, Hong Kong has kept its prosperity, stability and way of life,” says Lau, who is now vice-chairman of the semi-official Chinese Association of Hong Kong and Macau Studies.

He describes intervention by Beijing as “defensive moves”, saying the opposition camp still has a different understanding of “one country, two systems” and the city has yet to form a government that can rule effectively.

“Those were only defensive moves … amid challenges against the central government’s power and the Hong Kong government’s ability to govern,” he says.

“It was not because the central government wanted to change its policy. If Beijing thought the system did not serve any national interest, it would not keep it.”

The sixth handover anniversary on July 1, 2003, marked a turning point, when a mass protest prompted Beijing to tighten its grip. Some 500,000 people took to the streets fearful of a national security law being pushed by the city government and in protest at the handling of the deadly outbreak of Sars, or severe acute respiratory syndrome.

In response, Beijing launched an offensive calling for patriotism and the need for Hong Kong to be governed by those who “love the country and the city”. It came just as pan-democrats were gaining political momentum to push for universal suffrage for the chief executive and Legislative Council elections in 2007 and 2008 respectively.

The so-called patriotism debate showed the central government was not only worried about the city’s development, but also no longer wary of weighing into the other system when necessary. It believed economic woes were at the heart of the discontent and began to distribute favours, such as opening up the China market to local professionals and allowing waves of cash-rich mainland visitors into the city. However, things remained static on the political front. Not only were calls for universal suffrage rejected, but also the National People’s Congress Standing Committee ruled democratic reforms could not be launched without its approval.

There were hopes that a new page had been turned in 2005 when Donald Tsang Yam-kuen replaced Tung Chee-hwa as chief executive, and two years later Beijing delivered its long-awaited timetable on universal suffrage, pinpointing the 2017 chief executive election at the earliest with polls for the legislature to follow. Public confidence in “one country, two systems” surged to 75 per cent.

But the optimism proved short-lived amid claims there were two forces holding sway in Hong Kong, namely the city government and Beijing officials at the liaison office. This raised serious questions about Article 22 of the Basic Law, which forbids any central or municipal government department from interfering in local affairs.

Things worsened in 2012 when the government was forced to withdraw the proposed introduction of national education in the wake of mass protests by both parents and students, who described the move as brainwashing and the imposition of blind patriotism from the top. Fifteen years after the handover, it showed suspicions remained.

The divide made Beijing even more wary of giving the city a free hand to chart its democratic course. In June 2014, the State Council, or cabinet, dropped a bombshell by issuing a 15,500-word white paper on the “accurate” understanding of “one country, two systems”.

Beijing, it stressed, had comprehensive jurisdiction over Hong Kong. Instead of having full autonomy, the city was only given the power to run its affairs as authorised by the central government. In other words, the autonomy of the city was limited to what Beijing was prepared to offer.

Amid concern that the city might drift even further under a popularly elected leader, in August 2014 Beijing imposed an unexpectedly tight electoral reform framework. It was eventually voted down by the pan-democrats. More significantly, the package sparked Occupy, a civil disobedience movement that launched demonstrations, shutting main streets for up to 79 days, the longest protests in Hong Kong’s history. The patriotic camp countered with rallies in support of the government, opening wounds in society that are yet to heal.

In 2015, the mysterious disappearance of five Causeway Bay booksellers and their reappearance in mainland custody raised serious questions over Beijing’s commitment to upholding the two systems.

The incident involving the men, said to have angered the political leadership by selling salacious, speculative tales about them, was seen as an erosion of citizens’ rights and freedoms. Britain described it as a serious breach of the Joint Declaration. More recently, the rise in a sense of localism, of belonging to Hong Kong, has given way to breakaway sentiments and the rise of pro-independence groups that stress the “two systems” rather than “one country”. The controversial disqualification of two pro-independence lawmakers and attempts to ban others show Beijing will not tolerate any such illusions.

Former Democratic Party chairman Albert Ho Chun-yan says Beijing should loosen its grip, as “one country, two systems” has become “narrow and distorted” since 1997.

“With increasing control, Hong Kong will lose its status in the country. Beijing must stop its wrongdoings,” he says.

But to many loyalists, the problem lies with those who resist closer integration.

“Nowadays the exchange between Hong Kong and the mainland is getting closer. But radical pan-democrats resist the trend and cause some kind of man-made barrier, which does absolutely no good for Hong Kong,” says Ip Kwok-him, a local deputy to the National People’s Congress and former lawmaker .

That Hong Kong is an inalienable part of China is indisputable. Over the years, the city has made use of its special status to tap economic advantages over the border, so much so that some industries have become overly dependent on the mainland economy and are going through painful restructuring. But the trend for further economic integration appears irreversible. Lack of confidence in “one country, two systems” is attributed to worries that the “two systems” has been increasingly downplayed at the expense of “one country”.

As we contemplate what is to come after 2047, it is important that the city continues to defend “two systems” on the basis of “one country” – and for Beijing to also protect the principle.