As a kid, session musician Stevie Salas would savor the classic concert movie Bangladesh, which chronicled George Harrison’s all-star benefit show from 1971. “How did I watch that movie over and over and never notice that, standing right next to George, was this giant Native American guitar player named Jesse Ed Davis?” Salas asked. “I just thought ‘Wow, he’s a cool-looking guy.’ It’s amazing to me that I never made the connection.”

That’s especially amazing considering Salas himself is Native American. Yet it was only decades later, after Salas made a conscious effort to seek out other indigenous people in popular music, that he looked into Davis’s history. Over the course of his research, the sideman for stars such as Rod Stewart and Mick Jagger found a wealth of overlooked information about the deep impact Native people have had on a variety of American musical genres. His research, and that of others, has found its way into a revelatory new documentary titled Rumble: The Indians Who Rocked the World.

The movie, for which Salas serves as executive producer, illuminates how Native North American music and musicians influenced the creation of the blues, the development of jazz, the birth of rock’n’roll and even the elaboration of country music. Mainstream stars such as Jimi Hendrix, Robbie Robertson, Hank Williams and Loretta Lynn can all claim varying degrees of indigenous blood. “This is buried history,” says Catherine Bainbridge, director of Rumble. “Once people hear about this they think, ‘Wow, how did I not realize this before?”

Rumble takes its name from a seminal slice of rock’n’roll created by guitarist Link Wray, a Shawnee Indian from North Carolina. A 1958 hit, Rumble introduced the world to the “power chord”. The song was banned in New York and Boston for fear that the mere sound of that amped-up guitar might incite riots. “Jimmy Page and Jeff Beck used to play air guitar to Rumble,” Salas said. “But when I told Jeff that Link was Indian, his jaw dropped.”

“When Link Wray was a boy, the grand wizard of the KKK made a deliberate attempt to go after indigenous people,” Bainbridge said. “When his mom was 10 years old and walking to school, a bunch of white girls surrounded her and broke her back. She wore a brace for the rest of her life. That’s the violence Link came out of.”

While the movie makes clear the physical threat, and cultural erasing, that indigenous peoples endured in the US, its focus lands on the stirring sounds the tribes contributed. “When people hear the traditional music of the American south, they say, ‘That’s Indian music? I thought that was African music,’” the indigenous music historian Pura Fe says in the film. “All of the music of the south was informed by the land, and therefore by us.”

Bainbridge stresses that without African American people, there would be no blues and no jazz. “They’re the center of it,” he says. “But their experience in America was mixed with the influence of the indigenous people.”

In fact, many African Americans had children with indigenous people, as did whites, ensuring a broad cultural mixing. Yet because of the zeal to kill any Native claim to the land, and the subsequent ethnocide its people faced, many Native Americans chose to pass as either black or white. “In the time of my grandparents and great-grandparents, nobody wanted to be an Indian,” Salas said. “You were seen as lower than a wild animal.”

On Salas’ birth certificate, his parents identified themselves as white. Masking of that sort further suppressed the story of indigenous contributions. The film attempts to sift out and distinguish every strand of that influence. It traces them back to the beginning of Delta blues with the artist Charlie Patton; historians agree that Patton was between a quarter and one-half Choctaw. “When the African poly-rhythms met the Native American four-on-the-floor beat, that’s where you had the blues,” Bainbridge said. “That’s the beginning of what we consider modern American music.”

An interesting segment of the film deals with the Neville Brothers, who are seen by most listeners simply as ambassadors of New Orleans, In fact, they boast a Choctaw heritage. Within the film, Cyril Neville stresses the importance of Mardi Gras to Indians. “Tourists think of it like Halloween,” Salas said. “But to these guys it’s the only time they’re allowed to dress like who they are and not get in trouble.”

In the realm of jazz, the movie tells the story of Mildred Bailey, who grew up on the Coeur d’Alene reservation in Idaho. She became known as “the queen of swing” in the 1930s, influencing stars such as Bing Crosby and Tony Bennett. In the realm of folk, the first singer from the genre signed to Columbia Records wasn’t Bob Dylan but Peter La Farge, who sang of Indian rights. His work inspired Johnny Cash to later sing about the cause, to his commercial detriment. Buffy Saint-Marie, a Cree, wrote the folk standard Universal Soldier, which later became a hit for Donovan.

During the psychedelic era, Indian styles became part of hippie fashion. Bainbridge, who researched the representation of indigenous people in Hollywood for her documentary Reel Injun, said no nation sported the thin headband worn by hippies. “That was a creation of Hollywood to keep the wigs on the actors,” she said. Jimi Hendrix wore fringe and beads, something fans saw merely as trendy. In the film, his sister explains that he wore those clothes to honor his Cherokee grandmother.

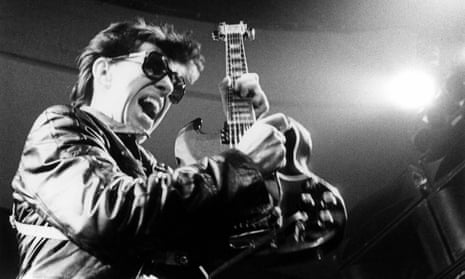

The film also covers Jesse Ed Davis, a Kiowa Indian, who entered the mainstream in the early to mid-70s, when he became a guitarist-for-hire for classic rock stars such as John Lennon, Eric Clapton and the Faces. During the same period, the band Redbone flaunted their heritage from the Shoshone and Yaqui tribes by wearing Native clothing on TV while performing their classic pop hit Come And Get Your Love. Robbie Robertson, of the Band, talks about learning to play guitar as a boy growing up on the Six Nation Indian reservation as a proud Mohawk. He repeats revealing advice from his mother about how to navigate life outside: “Be proud of being an Indian but be careful who you tell,” she told him.

In Robertson’s birth country, Canada, a movement has been growing to treat indigenous people more fairly, and to acknowledge more of their story. In 2014, the label Light in the Attic Records issued Native North America Vol 1, which collected the classic work of indigenous rock and folk songwriters in Canada and the northern US. In 2018, the label will issue a second volume, and this month the label will also re-issue Link Wray’s three solo albums from the early 70s. At the same time, Real Gone Music has just released a compilation of Jesse Ed Davis’s best recordings from his early 70s solo albums, while Redbone has put out a fresh retrospective.

As smothered as much of this history has been, Bainbridge believes there’s a connection to it all of us share. To illustrate, she quoted the late Native American poet John Trudell, who is heavily featured in the film. “John always said that there’s a genuine desire for all of us to connect to our indigenous past, however far back that goes. As he put it, ‘At some point, all of us wore feathers and all of us wore beads.’”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion