20 years after handover, has the Hong Kong experiment failed? From Vancouver, it can look that way

Hong Kong immigrants in Vancouver take a grim view of the SAR – and some see parallels in the growing influence of mainland Chinese money on their Canadian home city

“The identity of Hong Kong ... everything will disappear” Anthony Chan

“One country, two systems is now gone.” Fenella Sung

“Look at Hong Kong ... it’s a shell of what it was.” Geoffrey Ho

“Mr 689 ... He broke the system, the values of Hong Kong.” Albert Ng

*

Twenty years after the Hong Kong handover, the mood in Vancouver is far from celebratory for some of the city’s dwindling population of HK-born residents.

Is their decidedly grim view across the Pacific clouded by a subconscious effort to reinforce the correctness of their choice of home?

Historian Dr Leo Shin, 49, is the convener of the University of British Columbia’s Hong Kong Studies Initiative. The project, to teach, discuss and study issues related to the city, was launched this year with a symposium, “Hong Kong: 20 Years After”.

He said that although there was a risk that Vancouverites opinions on Hong Kong would be tinged with nostalgia, the Hong Kong immigrant community was “well informed” and connected to their former home city.

Watch: Hong Kong’s 20 years in 4 minutes

Shin landed in Canada with his parents on June 7, 1989, one day after his graduation from Princeton University and “under the cloud” of the Tiananmen Square crackdown. “My family was in many ways typical of Hong Kong families in the 1980s. There was this diversification of opportunities [and] we had been planning to immigrate for a long time. But it just so happened that what was happening in Beijing made this occasion sadder than it would have been. It was a time of pessimism and anger in Hong Kong, and some of my family were coming straight from there,” said Shin.

“It was a sad occasion ... We didn’t talk about it. But we understood what was going on.”

Shin strives for academic impartiality in his work with the HKSI. But without taking an activist stance on the supposed decline of Hong Kong, he considers the fate of the city to be of intense relevance.

“What is happening in Hong Kong will affect and is emblematic of what is happening in Vancouver, Canada, the US and the rest of the world,” with respect to the influence of the mainland market, and the exertion of Chinese “soft power”, he said.

With the perspective of age and distance and the benefit of hindsight others interviewed by the Post look on the SAR with abject disappointment – and are more convinced than ever they made the right choice to stay in Vancouver.

Many others did not; thousands of Hongkongers who emigrated to Vancouver in the run up to the handover would later return to the SAR. From 1996 until 2011, the Vancouver census area’s Hong Kong-born population fell 14.3 per cent to 73,770, down from the pre-Handover level of about 86,000. In the same period, the number of mainland-Chinese-born Vancouverites soared 131 per cent, to 168,440.

The exodus back to Hong Kong was far more extreme than the 14.3 per cent reduction suggests; additionally, it has more than offset the thousands who continued to arrive until immigration from Hong Kong to Canada tailed off into the hundreds per year, in 2000. There are now estimated to be 300,000 Canadians in Hong Kong.

‘Underneath, it’s 95 per cent destroyed’

These numbers suggest many Hong Kong emigrants to Canada felt enough optimism about the SAR to return.

“You look at Hong Kong now ... it’s a shell of what it was,” said Ho, who regularly visits Hong Kong to visit his father. “On the surface – well, there’s good food, it’s business as usual – but underneath, it’s 95 per cent destroyed.”

He cites the encroachment of mainland interests on the financial sector, a police force that he “can no longer think of as Asia’s finest”, and a judiciary and legislature under mounting pressure from Beijing.

He sees no way out for a city he said was losing its identity. “I see it as a dying city. As long as the CCP is in power, and Hong Kong is part of China, that’s it. I could see in 10 or 20 years’ time they could amalgamate Hong Kong and Shenzhen, and even get rid of the name ‘Hong Kong’. Just call it Shenzhen.”

“I’m not exactly a glass-half-full person,” he said with a grim chuckle.

“You see the influence of Hong Kong [in Vancouver] is actually greatly diminished in the 20-year period since the handover,” he said. “I don’t listen to Canto-pop any more. I haven’t watched a Hong Kong movie in 10 years ... it’s the same over and over: everything is being changed to please the [mainland] Chinese market.”

The influence of Hong Kong [in Vancouver] is actually greatly diminished in the 20-year period since the handover

Non-Chinese Vancouverites weren’t so aware of the changes, he said. “Canadians in general are pretty naive.”

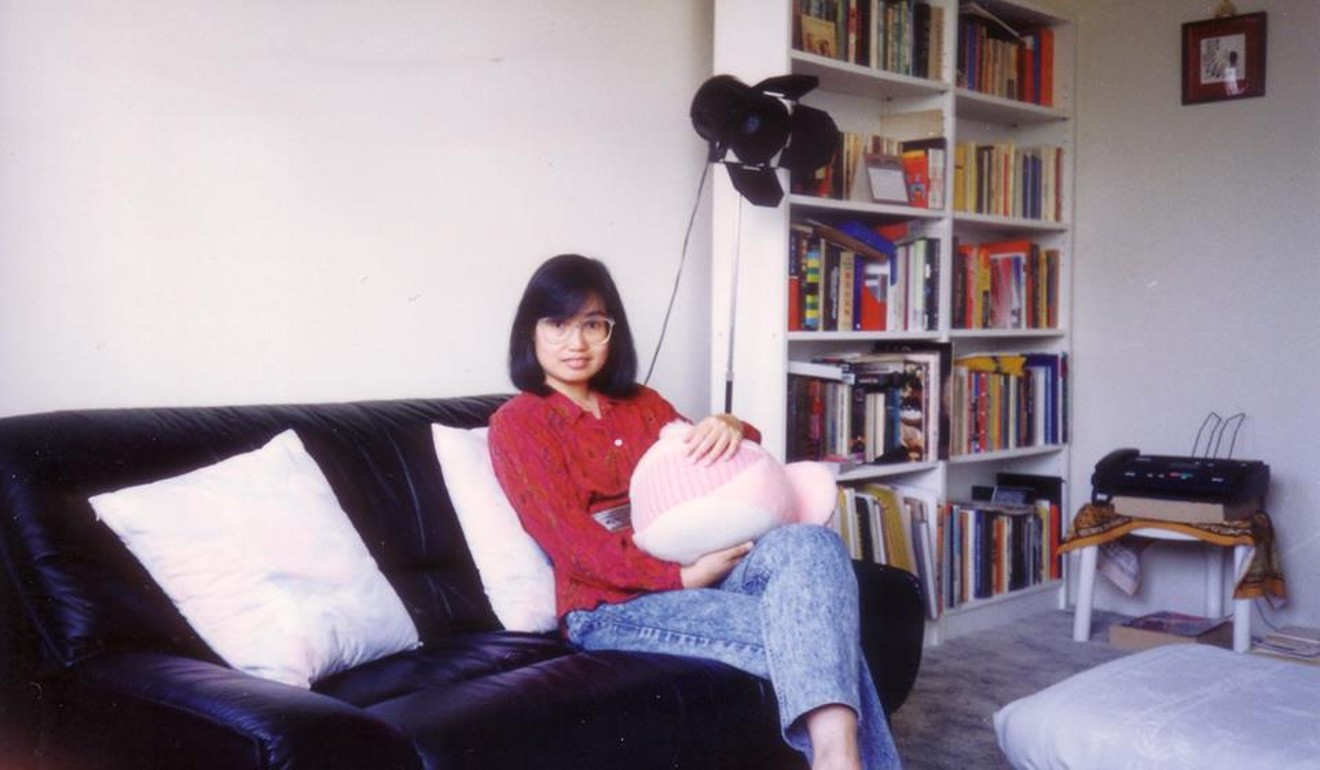

Fenella Sung, 59, is just as dubious about Hong Kong’s fate, and the parallels in Vancouver she says are a result of China’s “money power”.

“I can see here exactly the same kind of influences that I chose to turn my back on,” said Sung.

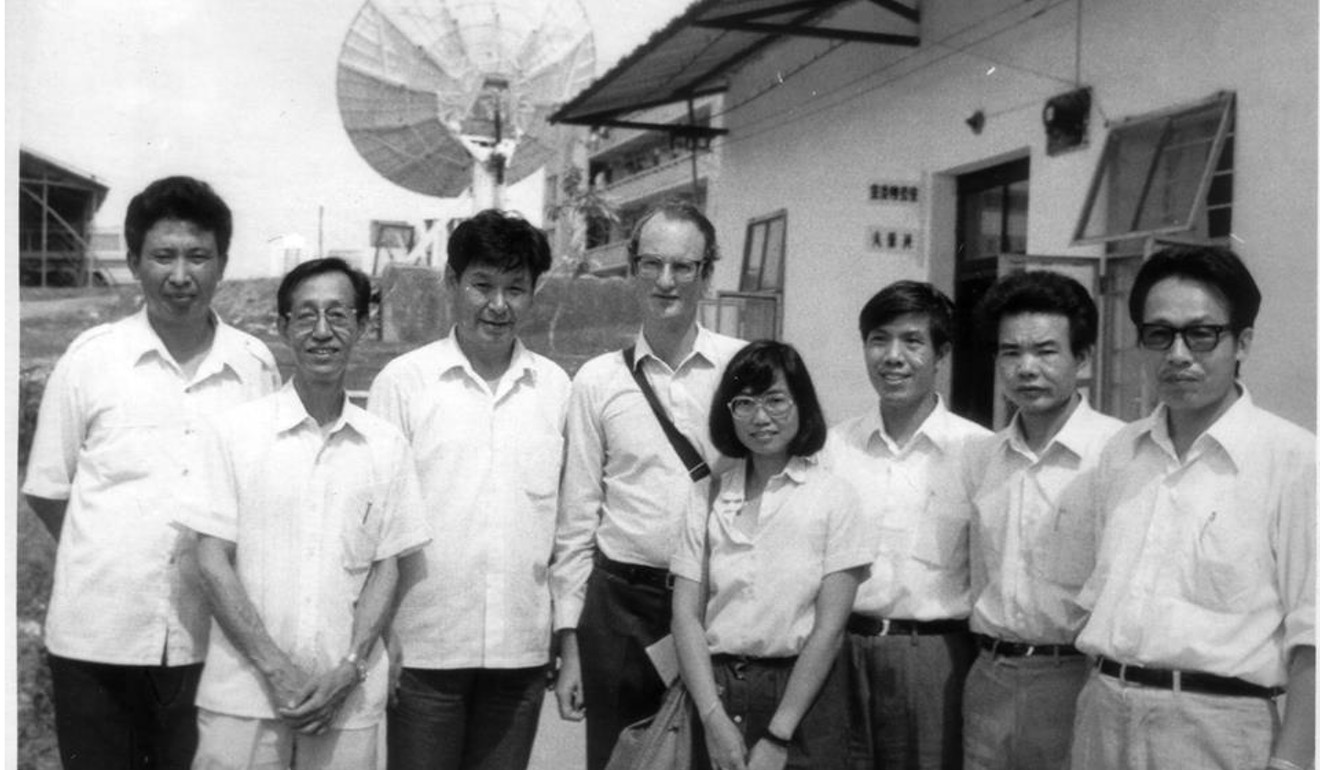

A former RTHK journalist, Sung began reporting on the mainland just months after the signing of the Sino-British Joint Declaration on Hong Kong in 1984, and would go on to cover the drafting process of the Basic Law, Hong Kong’s mini-constitution.

Her experiences reporting in China had already convinced her she could not stay in Hong Kong, but “the Tiananmen massacre was just the last straw”, she insisted.

The handover’s anniversary gives her nothing to cheer, she said. “Most people here like me left Hong Kong for a reason, unless we came with our parents ... so when there were discussions [among the HKU Alumni Association] about whether to celebrate the anniversary, our reaction is, ‘we didn’t even celebrate the handover when it happened. So why should we celebrate now?’”

‘The people in Hong Kong are stuck in a vacuum’

Anthony Chan, 50, wasn’t as pessimistic as Sung when he moved to Vancouver to attend university in 1989. He now has a human resources business here.

“My view about Hong Kong has changed since the handover,” he said. “Then, my views were conservative but optimistic – that Hong Kong would be a good influence on China.

“The people in Hong Kong are stuck in a vacuum. The people in Hong Kong can’t do anything. The government in Hong Kong can’t do anything. The government in China won’t allow them to do anything for themselves and everything has to be directed from China.”

[Hong Kong] will still be there, another city on the map. Another Chinese city. But if you are talking about the identity of Hong Kong ... everything will disappear I think

Chan said he still felt a deep emotional attachment to Hong Kong, and a few years after the handover he thought he might one day return, or that maybe his future children would (he now has a seven-year-old son). Now he doubts he will be back.

“If you just think of Hong Kong as a city, it will still be there, another city on the map. Another Chinese city. But if you are talking about the identity of Hong Kong ... everything will disappear I think.

“The years I grew up in Hong Kong, the city was relatively peaceful, people were optimistic. That’s what I miss the most. Now when I go back, I don’t see it. The confidence is gone.”

He had studied at the London School of Economics before working as a business planner in the private banking sector in Hong Kong. Now he is an insurance broker in Vancouver. He has only returned to Hong Kong a handful of times.

He said he made the right decision to move. “Definitely yes, but it’s a personal choice. My wife and I decided that there was no hope in hell for Hong Kong under a communist regime, so if we were going to move to another place we should do it while we are young,” he said.

“As you can see, 20 years after the handover, Hong Kong is going nowhere. It’s down the drain, because people are just trying to please the grandfathers up north. Because where the money is, that’s where the loyalty is.”

And he is unsparingly critical of the SAR’s “puppet” chief executives. “Look at the last one, Mr 689 [Leung Chun-ying]. He is the one who accelerated the downward effect. He broke the system, the values of Hong Kong.”

Why Hong Kong still matters

The attitude of some Hong Kong émigrés towards their former home city now seems fatalistic, but Shin, of the Hong Kong Studies Initiative, said it was crucial to maintain attention on the city, not in isolation but as a test-case.

Like Hong Kong since the handover, Vancouver is having to come to terms with the larger influence of mainland China, said Shin. “The Chinese communities here are having to also learn and find ways to adapt to this new reality,” something he said was “both interesting and complicated”.

“The trend and phenomenon of China playing a greater role in the world – there’s nothing necessarily wrong with that, but this has an impact on the world, on Canada. So Hong Kong is not just some city out there we pay attention to every five years or whenever there is violence or protests – it’s at the forefront of the influence of China.”

*

The Hongcouver blog is devoted to the hybrid culture of its namesake cities: Hong Kong and Vancouver. All story ideas and comments are welcome. Connect with me by email [email protected] or on Twitter, @ianjamesyoung70.