The White House Exaggerated the Growth of Coal Jobs by About 5,000 Percent

Donald Trump’s EPA head is touting bad statistics in defense of a foolish policy.

On Sunday’s “Meet the Press,” Scott Pruitt, the head of the Environmental Protection Agency, claimed that the U.S. has created 50,000 jobs in the coal sector since the fourth quarter of 2016. The statistic carries an important message for the White House. Trump has brought extraordinary attention to the decline of coal jobs, for which he’s blamed Obama-imposed regulations. Coal’s immediate bounce-back would represent a major early win for a president who has made promises to revive the economy of the 1950s, when mining was more dominant.

But Pruitt’s statistic wasn’t just flagrantly incorrect. It’s being used to support a nonsensical argument that the United States should orient its global policy based on a sector employing 0.03 percent of the economy, as there are fewer coal mining workers than there are people employed at Carl's Jr. franchises or Disney World.

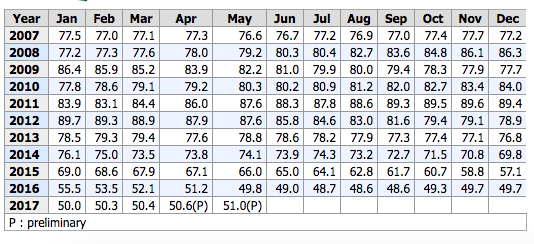

Quite simply, the coal sector has added about 1,000 jobs since October 2016—not 50,000. Coal could not have added 50,000 jobs in the last eight months, since that is essentially the size of the entire coal industry, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Pruitt’s statistic would otherwise imply that entire coal mining industry started in October. (Perhaps he meant 50,000 total mining jobs, but the vast majority of those positions have nothing to do with coal jobs; indeed, natural gas-mining workers might even be replacing them.)

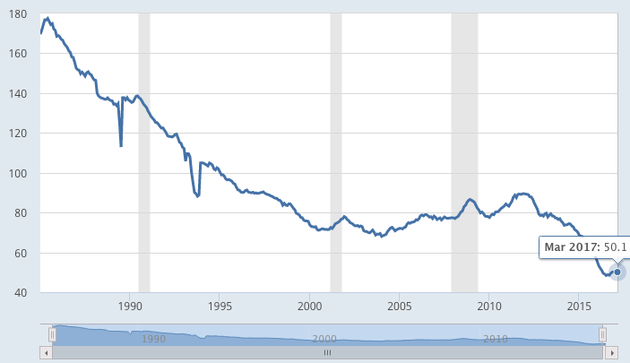

Total Coal Mining Jobs, in Thousands

Is Pruitt at least directionally correct that coal mining has sprung back to life under Trump? That’s a hard case to make. Coal-mining jobs grew by 1,000 in the five months between July and November 2016, when Trump was elected. Coal mining jobs grew by 1,000 in the five months between January and May 2017, when Trump was president. Not much acceleration there.

Total Coal Mining Jobs, in Thousands

Trump has blamed Barack Obama for the steep decline in coal jobs in his first seven years in office. This is part of a longer trend. The number of people employed in coal mining fell from 178,000 in 1986 to 86,000 when Obama became president, and then declined rapidly in the last eight years. Why?

While the Trump administration focuses on Obama’s environmental regulations, Charles D. Kolstad, a senior fellow at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research, says a confluence of factors dating back to the 1970s are the better place to look. First, railroad deregulation in the 1970s made it cheaper for coal mined west of the Mississippi—which has been more productive for decades—to be shipped across the country. Since then, western coal output has grown by 200 percent, as more labor-intensive mining east of the Mississippi has declined. Second, new fracking technology and the natural-gas revolution shifted fossil-fuel production away from coal, as solar and wind technologies expanded. Natural gas's share of U.S. electricity has tripled since the late 1980s, growing by almost the exact share that coal has lost. In short, coal’s long decline has several structural causes, and it’s unlikely that environmental policies will dramatically improve the prospects of the industry. “We’re just simply never going to go back to the 1950s and the 1960s in terms of coal-mining jobs,” Ben Bernanke, the former chairman of the Federal Reserve, recently told Vox.

But there is a broader point here. The Trump administration has held up coal miners and the steel industry as favored classes, worthy beneficiaries of the administration’s “America First” approach to governance. "I was elected to represent the citizens of Pittsburgh, not Paris," Trump said in a speech defending his decision to pull out of the Paris Accords. But it’s strange to build a national economic policy—much less a global diplomatic policy—around an economic sector that employs just 50,000 people, far less than the number of jobs in the solar industry. In fact, Pittsburgh itself stands as evidence that coal and steel are no longer central to the economy: The city has dramatically changed its industrial mix since the 1970s and its largest employers today include the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and Carnegie Mellon University.

When discussing coal jobs, Pruitt didn’t just demonstrate a disturbing carelessness with the truth. What’s worse, these bogus statistics are being used to support a backward policy, in which Trump is retreating from the United States’ global leadership position on climate change to save a handful of jobs in a small, structurally declining industry—when really, the future of economic growth is actually a lot like Pittsburgh’s—in technology, health care, and education.