Americans began the 20th century in bustles and bowler hats and ended it in velour sweatsuits and flannel shirts—the most radical shift in dress standards in human history. At the center of this sartorial revolution was business casual, a genre of dress that broke the last bastion of formality—office attire—to redefine the American wardrobe.

Born in Silicon Valley in the early 1980s, business casual consists of khaki pants, sensible shoes, and button-down collared shirts. By the time it was mainstream, in the 1990s, it flummoxed HR managers and employees alike. “Welcome to the confusing world of business casual,” declared a fashion writer for the Chicago Tribune in 1995. With time and some coaching, people caught on. Today, though, the term “business casual” is nearly obsolete for describing the clothing of a workforce that includes many who work from home in yoga pants, put on a clean T-shirt for a Skype meeting, and don’t always go into the office.

The life and impending death of business casual demonstrates broader shifts in American culture and business: Life is less formal; the concept of “going to the office” has fundamentally changed; American companies are now more results-oriented than process-oriented. The way this particular style of fashion originated and faded demonstrates that cultural change results from a tangle of seemingly disparate and ever-evolving sources: technology, consumerism, labor, geography, demographics. Better yet, cultural change can start almost anywhere and by almost anyone—scruffy computer programmers included.

What came before business casual? Basically, people wore suits. The norm was starched collars, overcoats, hats, and more hats. Americans dressed up for work, and they also dressed up for restaurants, for travel, for the movies. But as those other venues began to “casualize” by the 1950s, the office (and church) retained a formal dress code, by comparison. Well into the 1970s, companies gave employees manuals to outline official dress policies, but everything depended on the management’s need or desire to enforce them. Little by little, often-ignored infractions eroded the sanctity of any top-down policy: hose-free legs when the weather permitted, a tweed blazer for a day with no client meetings, loafers instead of dress shoes. Cultural change occurs most quickly when it is led by the people, for the people.

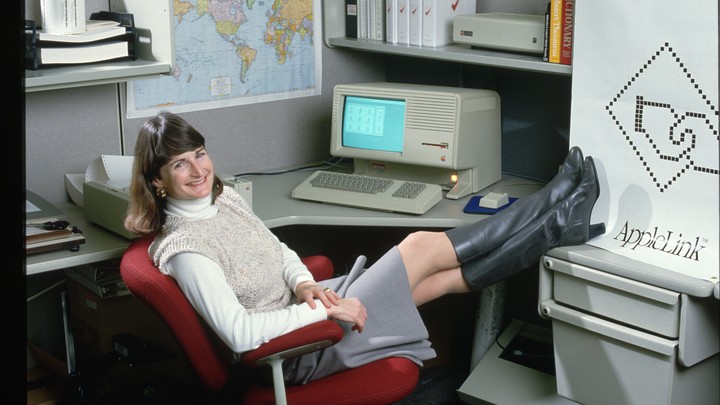

And in Silicon Valley in the mid-1980s, the people weren’t interested in adhering to old norms. Businesses there put an emphasis on streamlining management decisions and shortening the lag time between planning and implementation. Tech firms were insular, self-regulated, and male-dominated—a fertile combination for discarding norms and celebrating rule-breaking. Restrictive clothing worn for appearances’ sake was inefficient, and Silicon Valley was all about efficiency. Sport coat? Put it on the back of the chair. Places such as Atari, Apple, and Sun Microsystems embraced the 80-hour workweek, and their clothes proved it. The cover of 1983’s humorous The Official Silicon Valley Guy Handbook showed the world what geek chic looked like: “an unkempt corduroy jacket,” “drab 100% cotton shirt,” and “econo-brand athletic sneakers.”

Khaki pants and a button-down collar shirt, both Silicon Valley standards, became the baseline for dressing down, which made a certain amount of sense given that both garments were conceived in practicality. British soldiers in mid-19th-century India wore khaki for its durability, and because it blended in with the landscape. The fabric found popularity in World War I, but is most famously associated with the men deployed to the Pacific in World War II. Upon returning to the workforce, veterans did not want to give up their khakis. The button-down collar, meanwhile, came from the polo fields of England—one simply couldn’t bear having a collar flapping up in one’s face when attempting a “ride-off.” Brooks Brothers claims it brought the button-down to America in the early 1900s, and within 20 years, the soft collar eclipsed the hard version, which was removable (along with cuffs) for easy cleaning. Young women took to the shirt in the late 1940s, pairing it with Bermuda shorts.

Today, Silicon Valley has taken this spirit of sartorial pragmatism to its logical extreme. Steve Jobs and Mark Zuckerberg are associated with signature outfits—a black, mock turtleneck for the former and a gray T-shirt and hoodie for the latter. Zuckerberg explained: “I really want to clear my life to make it so that I have to make as few decisions as possible about anything except how to best serve [Facebook’s] community.” So, fashion and formality are frivolous? That’s the same logic that killed off the lavish ensembles of the French court and made way for the post-Revolution sack suit, a change that set a standard for menswear for nearly two centuries.

Both the creation and the adoption of business casual confirm what every teenager knows: Dress standards are a product of their environment. The same unspoken groupthink that kept East Coast employees in power suits with padded shoulders (a la 1988’s Working Girl) encouraged tech employees toward the basic elements of business casual, and even more informal garments, such as T-shirts, sweatshirts, athletic socks and, in some cases, jeans. In the 1960s, the sociologist Herbert Blumer termed this process “collective selection” and he argued that a given group sets the parameters for what is appropriate to wear (or not wear). Collective selection, Blumer wrote, happens when “people [are] thrown into areas of common interaction and, having similar runs of experience, develop common tastes.”

The fact that a California industry fueled the origin of a new office style is hardly coincidental. The state became the epicenter of casual dress in the 1930s, and laid claim to both a thriving garment sector and the cultural influence to define fashion trends for the country at large.

It was also not a coincidence that business casual arose from an industry that was in the 1980s dominated by men even more than it is now. The inherent tension between women’s appearances and a male-dominated workspace made casual dress for women loaded to begin with. Some scholars say that women wear heels to get men to respond to their requests for assistance or as a tool to compensate for their smaller physical stature. But do heels qualify as business casual? What about a sleeveless blouse? Walking shorts? “Sometimes” is a more confusing answer than “no.” By the early 2000s, journalists volunteered themselves to help women navigate these questions. Magazines, newspapers, and trade publications offered compare-and-contrast pictures, sidebars with helpful hints, and the always-useful lists of do’s and don’ts, including, “As a rule of thumb, if you can wear it to ‘The Club,’ you can’t wear it to work.” Many women still struggle with just how much of their body to expose in casual dress environments. A recent study found that 32 percent of supervisors named “too much skin” as one of their biggest problems with how their employees were dressing, right after “too casual,” at 47 percent.

The slow-but-steady adoption of business casual through the 1990s and early 2000s demonstrates the piecemeal way that cultural change actually develops. West Coast employers adopted business casual more quickly than East Coast employers. Industries that required long hours at computers and those that did not value formality as part of their public image grew more casual more quickly. Salaried office staff in the auto industry, for example, warmed quickly to the idea. An industry publication noted in 1995 that “business casual also has become a popular way for companies to reflect their changing workplace,” which as one engineer explained, emphasized “the best business practices as opposed to traditional practices.”

For the most part, those who had more interaction with the public, or clients, went by one set of standards; those who worked behind the scenes had another. Bankers and lawyers naturally had a slower go. In 1998, a banking exec told The New York Times that even though dress-down days “are a hot item” and “it’s been brought up time and time again,” his bank was “high-profile” and required workers to wear business attire. In 2000, what was then Chase Manhattan Bank took its Park Avenue office business casual, but only last year did JPMorgan (which by then had merged with Chase) change its dress code. Corporate image and employees’ desires helped define who went casual and when.

Another dimension of the way cultural change unfolds: There is always a point when “We don’t do that” slides into “Yeah, we do that.” “Casual Friday” became a palatable, kind-of-fun way to introduce new standards into the office. By 1996, nearly 75 percent of American businesses had a dress-down day—a figure up from 37 percent just four years earlier. Casual Fridays allowed both managers and employees to “collectively select” what constituted casual dress for their specific environment. Still, HR managers struggled to contain casual to just Friday or to provide guidance for an office that was proactively “going casual.” Business casual proved hard to define. In 2000, one uncertain office worker told researchers from the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, “Now it’s what kind of slacks, what kind of shirt, what’s acceptable and what’s not. The ranges and limits are tested, and they are a lot more ambiguous.”

Still figuring out how to market the mix-and-match nature of the garments—quite different from selling a suit—retailers struggled to meet consumers’ needs. “I don’t think department stores are good at explaining the why of it,” a consulting firm executive told a reporter for Women’s Wear Daily’s eight-page insert in September 1995 called “Casual Evolution.” Rather than showing buyers “how to put the outfit together for the kind of business they are in,” department stores stood by outdated floor plans that separated pants from shirts and shoes. Companies such as The Gap or The Limited that were in charge of both their manufacturing and their retail provided shoppers with an achievable and versatile look.

Confusion among consumers died off in the early 2000s, but for managers, one question loomed: Does casual dress make workers less productive? A chorus of academics came up with an answer: not sure! Some managers argued it empowered workers to bring individuality to the workplace, which in turn inspired creative thinking. Other managers considered casual dress a distraction that too often devolved into sloppy habits.

Thirty years into business casual, many Americans live without dress belts or socks; some don’t even have an iron, and even more don’t use the one they do have. The infiltration of casual clothes into the American wardrobe is complete, but standards are ever changing. Driving the change today is a generation of Americans who are less beholden to rules like “no white shoes after Labor Day.” Consultants say that as workers, Millennials “tend to be uncomfortable in rigid corporate structures,” value “a flexible approach to work,” and seek “similar things in an employee brand as they do in a consumer brand.” Today’s young workers didn’t have to shake off the shackles of formality that plagued the previous generation; clothing for them is less about fitting in than standing out. Clothing has always been personal—after all, we wear it on our bodies—but everyday fashion is moving toward the idea that people can wear what they want, as long as it is authentically them. This principle will define what people wear to work in the coming decade.

There’s always a pushback as dress standards change. Many today might be tempted to watch an episode of Mad Men and think, “Why don’t people dress that nicely anymore?” But clothing standards are born of their time and place. What people wear is dynamic, but not capricious. So anyone who frowns upon the hoodie-wearing coworker one cubicle over would be well advised not to judge. If history is any indication, that’s what everyone will be coming to work in soon enough.

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.