To win a prize that carries George Orwell’s name is a source of pride for any journalist. But it was impossible for me to accept it in a city struggling to come to terms with the horrors of Grenfell Tower without being forced to think about the relationship between pride and shame.

To think, too, about the kind of Englishness Orwell stood for and the urgent need to reclaim it. For what his work still tells us above all is that there is a great difference between national pride and national vanity. If Brexit is a moment of English national vanity, Orwell always knew that English national pride had to start with a sense of shame – with anger at the ignominy of a society that treats some people’s lives as worthless simply because they do not have enough money to matter.

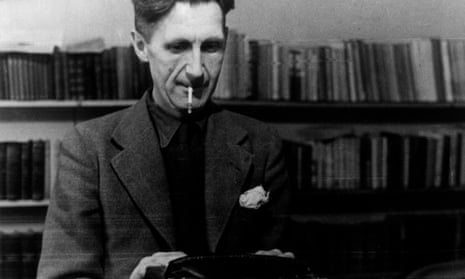

Orwell’s name resonates around the world but it does so because he seems, at least to outsiders like me, so profoundly, wonderfully and characteristically English. He represents a great English tradition that is sceptical, egalitarian, independent-minded and gloriously awkward. It is a tradition worthy of any nation’s pride. England urgently needs it now – and so does Europe.

But Orwell’s patriotism was not rooted in “all the boasting and flag-waving, the Rule Britannia stuff” he so despised. It had nothing to do with wishful thinking about national greatness. He would have known how much money was saved by using cheaper but flammable insulation tiles on a tower block: in The Road to Wigan Pier he tells us straight away why no hot water system was installed in miners’ houses: “the builder saved perhaps ten pounds on each house by not doing so”. He would have written about Grenfell Tower with precision and searing clarity and with a coldness that did not conceal the savage indignation burning underneath. And he would have insisted that doing so was an act of genuine English patriotism.

A nation that allows a Grenfell Tower to happen has lost the sense of shame without which there is no genuine national pride. It is the same kind of nation that gives way to the vanity of Brexit. One of the things that underlies the great Brexit upheaval is the resurgence of English nationalism – there are Scottish and Welsh and Northern Irish Brexiteers, but they are peripheral to the real action. The problem with English nationalism is not that it exists – the English have as much right to nationalist sentiment as anyone else – but that it does not know what it should be proud of. It has been buried in other constructs: the empire, the United Kingdom, Britishness. When you don’t know what positive claims to make, the easiest way to define yourself is as a negative. To be Us is to be not Them.

Brexit is, in large part, an expression of this negative idea of identity: English is not immigrant, not European, not the saboteurs and enemies within. And after that? Not very much beyond a cartoon of John Bull standing on the cliffs of Dover waving his fist at bloody continentals. The vacuum is filled with post-imperial fantasies and delusions of grandeur, with belligerence and nastiness.

But England is better than that and so is Englishness. Progressives have been reluctant, for noble reasons, to talk too much about Englishness. To do so is to risk falling into white nativist fantasies that exclude those who are not sons and daughters of some imagined Albion. Johnny Rotten, that most Irish of Englishmen, hit a nerve when he sang: “There is no future in England’s dreaming.” But perhaps there should be – not just a future, but a present reality for the hard, tough-minded English dreaming of a George Orwell and for another England at least as real as the obnoxious caricature that is now in the ascendant.

This may, like all collective identities, be largely an exercise in invention. It may even be itself in part a caricature. Perhaps it is a matter of reoccupying a stereotype. If you ask foreigners – and many English people themselves – to sum up the English attitude in a phrase, that might be “no-nonsense”. One version of this stereotype is stalking the land: bluff, proudly ignorant, at war with the complexities and ambiguities of contemporary realities. But there is a better version. What is Orwell if he is not a great enemy of nonsense? He taught us that nonsense is the cloak of power, violence and enslavement.

His prose is one of the sharpest scythes ever whetted to cut down the cant and lies that keep power in the hands of the few and the obfuscations that obscure the consequences for the many. He forged it, though, from materials that were very English: a tradition of radical thought and expression that goes back through many centuries all the way to the peasants’ revolt and John Ball’s great sceptical question: “When Adam delved and Eve span/ Who was then the gentleman?” The no-nonsense English tradition that Orwell inhabited combines a clarity of thought and articulation with an understanding that if things are being obscured, it is because something shameful is going on. It uses the idea of national pride, not to bolster smugness and self-delusion but to stir outrage at these shameful things. It says simply: we English are better than this.

Even in these shameful times, it is important for an outsider – which as an Irishman I certainly am – to say: yes you are. England is better than the shrinking of its public realm of mutual care that has led to Grenfell Tower. It is better than the reckless game-playing of a buffoonish ruling class that has led to the self-harming gesture politics of Brexit. It is better than the show it is making of itself on the world stage, the tragicomic spectacle of a nation in which no one has the authority to negotiate its future.

It is, after all, a country in which Orwell sprang from very deep traditions and in which those traditions of honesty, courage, egalitarianism and scepticism are, in spite of appearances, vibrantly alive.

Fintan O’Toole is a columnist with the Irish Times and winner of the 2017 Orwell prize for journalism