Margaret Atwood’s evergreen dystopian novel The Handmaid’s Tale is about to become a television drama. Published in 1985, it couldn’t feel more fresh or more timely, dealing as it does with reproductive rights, with the sudden accession to power of a theocracy in the United States, with the demonisation of imagined, pantomime villain “Islamic fanatics”. But then, feminist science fiction does tend to feel fresh – its authors have a habit of looking beyond their particular historical moment, analysing the root causes, suggesting how they might be, if not solved, then at least changed.

Where does the story of feminist science fiction begin? There are so many possible starting points: Margaret Cavendish’s 1666 book The Blazing World, about an empress of a utopian kingdom; one could point convincingly to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein as an exploration of how men could “give birth” and what might happen if they did; one could recall the 1905 story “Sultana’s Dream” by Begum Rokeya, about a gender-reversed India in which it’s the men who are kept in purdah.

And perhaps one of the starting points was here: on 29 August 1911, a 50-year-old man, a member of the Yahi group of the Native American Yana people, walked out of the forest near Oroville, California, and was captured by the local sheriff. He was known at the time and popularised in the press as “the last wild Indian”.

He called himself “Ishi” – a word in the Yahi language that means simply “man”. He was the very last of his people, and had been living in the wilderness alone, travelling to places he remembered from the time when his tribe had flourished, in the hope of finding some remnant of those he’d grown up with. When he realised they were truly all gone, when a series of forest fires meant he was close to starvation, he allowed himself to be found and taken in.

Knowing that he was the last surviving Yahi, Ishi was desperate to communicate some of the culture that would be entirely lost when he was gone. He ended up living with the director of the museum of anthropology at the University of California, Alfred Kroeber. He taught Kroeber as much as he could: demonstrated the skills of flint-knapping, explained his language, told the stories of his people one last time so they could be written down and preserved. He was particularly fond of children, Kroeber recorded. Ishi died in 1916, of tuberculosis. After his death, Alfred’s wife, Theodora, wrote a remarkable book about him, Ishi in Two Worlds, which relays as much of the Yahi culture as the anthropologists were able to record, and talks about Ishi’s own accounts of his life. To read it is to touch an intricate and beautiful civilisation that is now entirely gone, a place that can only be momentarily resurrected by an imaginative act, as unreachable as an alien world.

And the link with feminist science fiction? Theodora and Alfred Kroeber’s daughter was Ursula Le Guin, the science fiction author. Her novel The Left Hand of Darkness was published in 1969, at the start of the revolutionary women’s movement, and was one of the earliest pieces of feminist SF. It is about a man from Earth who travels to the planet Gethen, where the people have no fixed gender. He is by turns fascinated, appalled and deeply, sickeningly lonely. Everyone’s “normality” is someone else’s wilderness.

The association between some writers of feminist science fiction and the wilderness is surprisingly strong, in fact. Atwood grew up spending a large portion of each year in the Quebec woods. Her father was an entomologist – an insect man with a specialism in the solitary bee – who worked on ways to protect the Canadian forest industry from insect damage. Atwood’s early life included springs, summers and early autumns in a log cabin in the woods with no electricity, paddling canoes across clear forest lakes and cooking on an open fire. Alice Sheldon – who wrote under the pen name James Tiptree Jr, and after whom the James Tiptree Jr award for science fiction or fantasy explorations of gender is named – travelled extensively as a child among African peoples including the Kikuyu. Her parents were Herbert, an explorer, and Mary, a travel writer and war correspondent.

Of course, not every author of feminist science fiction was taught how to make a fire in the wilderness by her (or his) parents. But what interests me, and what links these stories, I think, is the sense of young people having been exposed early on to the idea that there are other ways of living which are equally valid, equally worthy of respect, equally troubling and equally beautiful. That other cultures and modes of existence make sense on their own terms. That however you’ve grown up, it would always be possible to do things differently. And having seen that, one can’t help reflecting on what the world would be like if we did decide to do things radically differently. Feminist – or let’s say gender-questioning – science fiction asks insistently, through careful construction of different societies, how much of what we think now, today, in generic western culture about men and women is innate in the human species and how much is just invented. And if we’ve invented it then could we, for better or worse, invent it differently?

The answers are often dystopian. The Handmaid’s Tale is probably the most famous work of feminist speculative fiction ever published; certainly it’s one with a huge and appreciative audience outside the borders of the “genre” science fiction and fantasy readership. It takes place in Gilead, a fundamentalist theocratic state in New England in which a Christian sect, “the Sons of Jacob”, has taken control. There’s been a precipitous decline in the birth rate, and the state has reverted to the biblical model of reproduction: powerful men have fertile young “handmaids” to bear children who will then belong to them and their wives. The novel follows one such handmaid, Offred – a name that sounds appealingly Anglo-Saxon until you realise it means “Of Fred”, Fred being the man who owns her. I read the novel as a teenager (a teenage Orthodox Jew, in fact) and realised very suddenly and certainly that if I were ever to get married I couldn’t possibly change my name, that I would never be able to hear it as anything but “Offred” from then on.

What makes The Handmaid’s Tale so terrifying is that everything that happens in it is plausible. In fact, everything – like the stratagem of the handmaids – has happened somewhere before. Everything in it has been praised by someone as the right, the good, the best, the only way to live. And Atwood had a horrifyingly prescient eye for how a state like Gilead could come to exist: “… after the catastrophe, when they shot the president and machine-gunned the Congress and the army declared a state of emergency. They blamed it on the Islamic fanatics, at the time … Newspapers were censored and some were closed down, for security reasons they said. The road-blocks began to appear, and Identipasses. Everyone approved of that, since it was obvious you couldn’t be too careful.” Eventually, women’s bank accounts are frozen, taken away from them, women are fired from their jobs. It happens step by step. How do you boil a frog? You turn the heat up slowly.

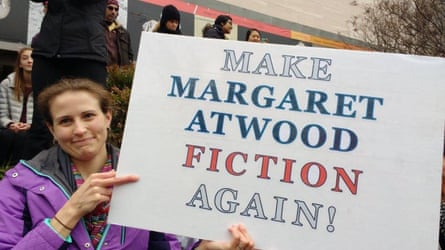

The politics of fear are always the same. They are easily recognisable in retrospect. They are easy to acquiesce in at the time. On the day of Donald Trump’s inauguration, one popular placard read “Make Margaret Atwood Fiction Again”. There’s no gain the women’s movement has made that can’t be taken away – a fact that will sound terrifying to some and a gleeful plan of action to others.

Writers of feminist dystopian fiction are alert to the realities that grind down women’s lives, that make the unthinkable suddenly thinkable. In Joanna Russ’s novel The Female Man, four women from four parallel worlds meet, travelling from world to world to see how their lives could have been different under a different system. The most sexist of all the realities she explores is also the one that is most economically depressed. It’s Jeannine, the woman from the world where the Depression never ended, who is so ground down that she barely believes she can exist without finding a man to marry her. Economic downturns make vulnerable people more vulnerable – and societies in trouble tend to retreat to an imagined past of certainty and stability. To put it another way: justice feels affordable in times of plenty, and starts to feel like a luxury in times of want. But anarchy can lead to new opportunities. In Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower, in which a young woman with “hyperempathy” founds a new religious order, people are hungry for change because the old ways haven’t worked, the US is plagued by deadly weather patterns that kill hundreds, and civilisation has collapsed to the point that it’s “crazy to live without a wall to protect you”. Feminist science fiction does have a way of finding resonances in the modern world.

Marge Piercy’s 1976 novel Woman on the Edge of Time offers another two possible futures, one utopian, one dystopian. Connie Ramos has been released from a mental hospital; she’s seeing visions of the future, which might be real or might be delusional. In one future, the human race has somehow managed to come to its senses about all kinds of prejudice, learning how to value the rich diversity of life – gay and straight, male and female, all ethnicities and physical characteristics. As one character says, when discussing valuing one trait over another in reproduction: “It’s one choice to breed carrots for our uses – especially leaving wild and variant gene pools intact. Is another to breed ourselves for some uses or imagined uses! For all we know, a new ice age comes and we might better breed for furriness than mathematical ability!” It’s a pointed lesson when contrasted with Connie’s visions of a dystopian future, where women are “cosmetically fixed for sex use”, and people boast about which multinational corporation owns them. The astonishing thing about considering Woman on the Edge of Time now is how we’ve inched closer to both her worlds in the 40 years since the novel was published. Yes, you can get cosmetic “fillers” on any high street. Yes, corporations continue to grow in power as if they were living things, merging and combining abilities. And at the same time it also doesn’t feel astonishing to read a scene of two men flirting and dancing together as it might have done in 1976. Utopias and dystopias can exist side by side, even in the same moment. Which one you’re in depends entirely on your point of view.

My latest novel, The Power, has been described as a dystopian thriller. In it, almost all the women in the world suddenly develop the power to electrocute people at will (they can electrocute women as well as men; also animals and inanimate objects – I based it on what electric eels do). And they use their power, slowly but surely, just as men do in our world today. Some of them are kind and some cruel. Some rape and some just have a jolly good time in bed with willing participants. Nothing happens to men in the novel – I explain carefully to interviewers – that is not happening to a woman in our world today. So is it dystopian? Well. Only if you’re a man.

That answer’s too simple, of course. It’s pat, and gets a laugh from an audience, but the relationship between our world and utopias or dystopias of all stripes is a complicated one. Can we make a perfect state, where everyone is happy and agrees that things are being run in the best of all possible ways? Equally, could we create a place that everyone would agree is evil and morally bankrupt? We’re a diverse bunch, human beings. Which helps explain that thing you cannot do for all of the people all of the time.

Le Guin has a beautiful long short story that I’d encourage anyone to read. It’s called “The Matter of Seggri” and it draws – as so much of her work does – on her deep sympathy with the position of the anthropologist, there to observe and understand, not judge and solve. Seggri is an alien world; it’s so much easier to do thought experiments about an alien world, it’s clean and isolates precisely the problem you want to talk about. Human beings on Seggri are born physically just like human beings are here, with only one significant difference: “there are 16 adult women for every adult man. One conception in six or so is male, but a lot of non-viable male foetuses and defective male births bring it down to one in 16 by puberty.” And this tweak changes everything. Women on Seggri marry each other – you can’t hoard the men for just one woman. Instead the men live in a “fuckery” and do athletics to show off their muscles. “All they’re allowed to do … is compete at games and sports … Nothing else. No options. No trades. No skills of making. They aren’t allowed into the colleges to gain any kind of freedom of mind.” People on Seggri say: “Men have to be sheltered from education for their own good.” Meanwhile, women set up home together, pursue their interests and hire a man occasionally for fun or to father a child. As one anthropologist character observes of Seggri: “Men have all the privilege and women have all the power.”

What I love about this story is how clear-eyed it is that all societies – at least all thus far constructed – leave something out. At a certain point in the story, one woman grieves over the curious behaviour of a fuckery boy who had fallen in love with her and wanted to be free to live only with her. “She thought, ‘My life is wrong.’ But she did not know how to make it right.” It’s a heartbreaking moment. So often when one’s life seems wrong, it’s the world that is wrong. But we do not know how to make it right.

Which brings us back to Ishi. He knew in 1911 that all his people were dead, that he would starve if he did not surrender himself to the alien force that had destroyed his family and laid waste his land. But 1911 was not a terrible year for everyone. The New York Public Library was opened that year, Orville Wright set a new world record for glider flight, and Ronald Reagan was born – that was probably nice for his parents at least.

Reagan famously described his vision of an America that would be a “shining city upon a hill” – a beacon of light and hope, a place that could show the world how to be better, an inspiration to all. A utopia. So let’s put those two things side by side and regard them for a moment. Reagan is a baby in the cradle, Ishi is in the forest, accepting that the Yahi people are gone for ever, wiped out by the settlers. Everyone’s shining city on a hill is someone else’s hell on earth.

Every utopia contains a dystopia. Every dystopia contains a utopia. The conclusion I’ve come to through extensive speculative fiction voyaging is that the best we can hope for, probably, is to create a society that tries hard not to leave people out. And to be vigilantly alert to the people we are leaving out, whoever they are. To listen. To try to make it right as often as we can. To imagine how it could be different. And as to whether The Power is a dystopia? Well, as nothing happens to a man in it that’s not happening to a woman right now, if my novel is a dystopia, we’re living in a dystopia today.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion