The semester is almost over and the rain is only supposed to hold off for a couple more hours, but a group of Campbell University golf management majors are stuck in Principles of Marketing instead of out on the course. Class on this Wednesday afternoon is about product life cycles, the natural progression from the time something new hits the market through a steady upward growth, peak, and then inevitable decline.

Most of the 40 students in the dim lecture hall look a bit sleepy, but the professor, Traci Pierce, remains admirably upbeat as she displays a chart from the textbook under the title "Adoption Processes Can Guide Promotion Planning." The graph shows that about two-thirds of the potential market for a given product adopt it during the growth phase. Another ten to fifteen percent are early adopters. The rarest category of consumers—about three to five percent, according to Pierce's slide—beat out even them.

"Are any of you innovators?" she asks the group.

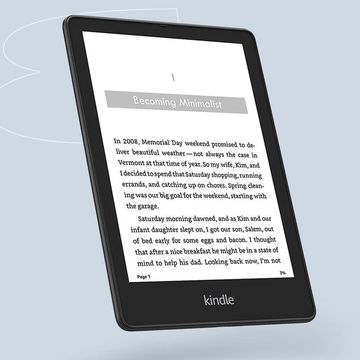

One young man in the back volunteers that he occasionally backs new products on Kickstarter, and Pierce thinks about it for a moment before agreeing that makes him an innovator. Meanwhile, in the second row, twenty-year-old sophomore Matt Nelson furtively checks his phone, tapping a burgundy sneaker on the floor to a beat only he can hear. It's not that Nelson doesn't enjoy Principles of Marketing—in fact, it's his favorite class, largely because it's the only one this semester that is relevant to what he now sees as his career path. But while Pierce seems like a highly competent and engaged teacher, Nelson could be the one at the front of the lecture hall.

Nelson had been on campus just two months when he started an absurdist-humor Twitter account dedicated to dogs. "Here we have a Japanese Irish Setter. Lost eye in Vietnam (?). Big fan of relaxing on stair. 8/10 would pet," he wrote above a photo of a friend's collie mix with two different-colored eyes on November 15, 2015. He was confident that WeRateDogs would become popular quickly because any joke about dogs on his personal account "would get more favorites than it definitely should have." His friend Matt, who was sitting next to him, became his first follower.

In the seventeen months since, nearly two million others have followed @dog_rates. A WeRateDogs book, a combination of greatest hits and original material, comes out in October. A mobile-phone game, created by a British company but earning royalties for Nelson, debuted earlier this year. His online store, which sells clothes and mugs emblazoned with popular sayings from the account, earns him in the low five figures each month. He has helped popularize "DoggoLingo," an Internet language that has now spread into the physical world. And he has become the figurehead of a very 2017 breed of humor that seamlessly blends two distinct fixtures of the internet—relentlessly irreverent snark and genuine appreciation of adorable animals. The result has become millions of Twitter users' favorite break from what can sometimes feel like a parade of horrors online.

In internet years, WeRateDogs may be older than its college-aged creator—it's exceedingly rare for a joke Twitter account to continue growing exponentially more popular after a year and a half. The next question, to borrow the marketing framework Pierce outlined, is when does WeRateDogs' life cycle hit its peak and begin to decline? When Nelson graduates in two years, will he still be making a living as the CEO of WeRateDogs LLC? "Initially, the way I thought of it was like a pathway to a job in writing or a job in comedy," he tells me over lunch in the on-campus Chick-fil-A. "Now the goal is to make this the job. I thought this was going to lead to opportunities, which it has, but now this is the opportunity."

In Principles of Marketing, "innovator" means buying someone else's creation earlier than other people. In Nelson's world, it's no fun if you're not the one doing the creating. And while his creation may not strike a middle-aged marketing executive as particularly innovative, Nelson's next-level understanding of internet escapism has turned WeRateDogs into a burgeoning empire before his twenty-first birthday. Now he just has to figure out how to keep expanding it past his twenty-second.

Stories about social-media fame are generally told as stories about happy accidents—an unknown user posts something intended for a few friends, but through some act of providence or alchemy it "goes viral" and turns its creator into a star overnight. That is not the story of WeRateDogs. To Matt Nelson, Twitter has always been a game to be won.

Of course, to Nelson, everything has always been a game to be won. His sister, Amanda, now twenty-two, was the academic star; she graduated this year from the University of Michigan. His brother, Mitchell, now seventeen, was the laid-back one; he just finished his junior year in Charleston, West Virginia, where the Nelsons moved when Matt was eight. Matt, his mother Barbra said, was "the intense one."

"As a kid, he was very competitive no matter what was going on," she said. "It could be as simple as Easter-egg hunting, and he wanted to win at all costs. Not every event in your family can be a competition; it doesn't always go over well with your siblings."

"If breathing was a competitive sport, it would be his goal to out-breathe everyone," his dad, Mark, added.

Three days after Matt was born, in northern Virginia in October 1996, he underwent open-heart surgery to repair a life-threatening congenital defect; a few years later, his cardiologist recommended he take up swimming, thinking it'd help keep him healthy. Nelson took to the sport quickly, and he spent his high school years competing in national swim meets and helping his team to four straight West Virginia state championships despite the fact that he was almost always the smallest guy in the pool.

He also competed in golf, which he learned from his grandfather and decided to make his career in high school. Intending to become an instructor, he chose Campbell, a Baptist university in rural central North Carolina, for its Professional Golf Management program, one of nineteen accredited by the PGA to train students to work in the industry. During his freshman year, he was on the course every day and competed in tournaments nearly every weekend; over the course of this year, though, golf has gradually taken a backseat. When I accompanied Nelson and three friends to play a round one afternoon, he warned me he was rusty—he hadn't played in two weeks, the longest dry spell since he first picked up a club. (He shot par over seven holes before the rain drove us inside.) "I love golf still, I just figured out that I'd rather be the member 10 years from now than the head pro 10 years from now," he says.

So the energy that once went into studying the golf industry is now devoted to running WeRateDogs, which he never intended to be more than a hobby. The premise is deceptively simple: Fans DM Nelson photos of their dogs (about 1,200 a day), and he rates them for other fans—1.99 million of them at last count—to see. But the ratings themselves, all of which now fall between 10/10 and 14/10, are essentially beside the point. The real magic is the delightfully surreal captions. One of my favorite WeRateDogs tweets shows two photos of a German shepherd puppy in the refrigerator, first sitting up and then lying between some packaged deli meat and a few bottles of Shiner Bock. "This is Duke. He sneaks into the fridge sometimes. It's his safe place. 11/10 would give little jacket if necessary." Dogs are "doggos" or "puppers." One of the account's early signature phrases was "oh h*ck," a silly censoring of an already-family-friendly word that strikes so many people as so funny that Nelson now sells hundreds of hats, mugs, and shirts with the phrase every month.

Eating lunch in the student center before Principles of Marketing, Nelson is dressed in a standard college uniform: long-sleeved t-shirt and shorts, baseball cap with its brim cocked at a 150-degree angle, blond curls jutting out above bright blue-green eyes that seem to physically lock onto whatever he's looking at. When I ask how often he spends time working on the site he doesn't pause before answering, straight-faced, "24/7." He's constantly monitoring his Twitter replies, whether in class or on the golf course with friends, and he deletes one out of every ten or fifteen tweets within the first ten minutes if it's not getting enough likes.

"Focusing on one thing is really how I prefer doing anything," he tells me over a chicken-salad sandwich. He doesn't see much point in parties, preferring to spend weekend nights catching up on emails or sleep. Still, he wasn't entirely prepared for the lack of activity on campus. There's no bar in town; the closest one is four miles west. ("I can't get in anyway," he tells me as a way of explaining why he hasn't joined many of his friends in getting fake IDs. "I look twelve.") The three restaurants—Moe's, Chick-fil-A, and The Oasis, a walk-up spot in the student center for burgers and sandwiches—are all closed by nine p.m. Freshmen and sophomores are required to attend chapel once a week. But for an aspiring golf teacher, the top-ranked PGM program felt fulfilling at first. Four semesters in, though, "that's kind of changed," he says. "Obviously my whole life has changed."

In the early days after he launched WeRateDogs in November of 2015, Nelson told an interviewer a story about how he came up with the idea. He was eating at Applebee's when a friend announced that his burger was a "10 out of 10." In a flash, it came to him: why not start a Twitter account dedicated to rating dogs?

But like so many inventor origin stories, this one is bullshit. He did take the first step while at Applebee's, setting up a Twitter poll asking his followers if they thought it was a good idea, but at that point he had been an intensive student of Twitter comedy for more than a year. There was no rating of a burger, just a sophisticated understanding of what makes animals internet gold and a bit of research to make sure no one had rated dogs before. (Someone had, in fact—Nelson's account is @dog_rates because @dogrates had been taken three months earlier. Its owner tweeted seven times in one day, rating each dog 10/10, and hasn't used the account since.)

"I figured that's what people wanted to hear; they want a Eureka moment for how I came up with it, but I just don't have that," Nelson says, sorting through emails before composing his nightly dog rating tweet in the on-campus Starbucks one weekday evening. He didn't mean to deceive anyone, he just wasn't sure how to answer the question and didn't want to appear unhelpful.

Nelson joined Twitter as a high-school junior in 2014 and quickly fell down the rabbit hole of what had become known as "Weird Twitter," a subculture of users who had been pushing the boundaries of the 140-character form through surrealist humor for around five years. (Many Weird Twitter users, it should be noted, object to the name Weird Twitter, though nobody has come up with a better one.) He discovered accounts like @jonnysun—a Ph.D student at MIT whose online persona is an "aliebn confuesed abot humamn lamgauge"—and he wanted to be a part of it. He started tweeting his own jokes, the vast majority of which he now considers embarrassingly unfunny, and while he came onto the scene too late to be a core part of Weird Twitter, he had about ten thousand followers by the time he tweeted his poll.

@dog_rates' first tweet, about an Irish setter who lost an eye in Vietnam, created a blueprint for what WeRateDogs would become, though without most of what are now known as the hallmarks of the account. The short, choppy sentences were common on Weird Twitter; he added the invented dog breeds and the rating-plus-evaluation structure of the final line.

The presidential campaign was already in full swing by the time the account launched on November 15, 2015: That day—less than 48 hours after Islamic terrorists killed 130 people in a series of attacks in Paris—France bombed Syria and then-Republican presidential candidate Jeb Bush called for the United States to declare war against ISIS. The weekend's heavy news cycle wasn't the reason Nelson started WeRateDogs that day, nor was it entirely incidental. He had decided the account would focus on dogs not because he's especially obsessed with dogs (though, he rushes to add, he is pretty crazy about his family's golden retriever, Zoey), but because dog photos performed well on his personal account. And he also knew, as we all do, that the reason dog photos perform well is because the news cycle is constantly horrific, and what better way to get away from it than through photos of cute pets?

"If you're in the wrong parts of Twitter, it can easily be described as a cesspool of horrible things. So in that way, you can see my account as an escape," he says. "You can pick and choose who you follow and adjust your experience by doing that, but there are people that don't have a choice but to deal with everyday news. I can see how for them it would truly be like, 'This is where I go to not hate everything.'"

Both absurdist-humor internet and cute-animal internet far predate WeRateDogs; Nelson's genius was not inventing them, but remixing them to form something new. And while those seem like opposite ends of the online-comedy spectrum—one so adorable it's sometimes saccharine, one so bizarre it's sometimes gruesome—both have their roots in the same Internet forum.

Something Awful began as the personal blog of a Missouri man named Richard "Lowtax" Kyanka, but by the mid-2000s it was a thriving online bulletin board with dozens of subforums and tens of thousands of paying users. Now perhaps most famous as the site behind the meme that inspired two teenage girls in Wisconsin to stab their friend in an effort to impress a fictional character called Slender Man, Something Awful's message boards also birthed I Can Haz Cheeseburger?, one of the first sites for animal memes, and Weird Twitter.

Kyanka's site was also the original home of Dogspotting, perhaps the most direct forefather of WeRateDogs. Though Nelson had never heard of Something Awful until I told him about it—he was two years old when the site launched—he knew of Dogspotting's Facebook group, which grew out of the forum around 2008 and still has about half a million members (a standalone Dogspotting app has a fraction of that). The gist was straightforward: See a dog (your own doesn't count), describe it in as much detail as possible, and wait for other members to assign you points based on the dog's characteristics and actions, plus the creativity of your retelling.

"I'm a terrible nerd and spent way too much of my time playing video games and like to see numbers go up, so I thought, 'What sort of combos and modifiers can I add?'" founder John Savoia, now twenty-nine, tells me. "Then you start to codify it and it gets more complex, and it all sort of spiraled from there. You get a sense of, 'I am part of this, that half a million people can see this cute dog I found.'"

"I'm not pretending that I reinvented the wheel with WeRateDogs, but taking the time to find the voice and craft the voice, I spent 24/7 in the beginning doing that, and that is why it's successful," Nelson tells me. "Nothing's original anymore. So you have to put your own spin on a thing that already exists."

WeRateDogs is perhaps the perfect illustration of the growth of once-cult forms of internet humor: Nelson learned from Weird Twitter, but cut the edgier, more NSFW parts. And going mainstream has paid off, literally. Weird Twitter was a members-only private club; WeRateDogs LLC is a diversified company.

Nelson can't quite pinpoint the moment a humorous Twitter account he opened while sitting at Applebee's turned into a business. Was it in December 2015, the first full month of WeRateDogs' existence, when he signed his book deal? Was the next month, when a stranger DMed him to offer $10,000 for what was then an account with a couple hundred thousand followers? Was it in February 2016, when a fraudulent copyright claim from someone trying to sabotage him temporarily shut down his account and led him to consult with an agent who became his mentor? Was it that spring, when he hired his first two employees, one of whom was the same guy who had tried to buy the account?

Or perhaps it was that September, when a Twitter user named Brant Walker questioned the premise of Nelson's account and unwittingly paved the way for the one-liner that catapulted WeRateDogs to new heights of fame. "your rating system sucks," he wrote. "Just change your name to 'CuteDogs'."

"Why are you so mad Bront," Nelson responded five minutes later, using a Weird Twitter convention of slightly altering someone's name for effect.

"well you give every dog 11s and 12s. It doesn't even make any sense," Walker responded within 60 seconds.

Four minutes passed, then Nelson tweeted the sentence that changed his life again: "they're good dogs Brent."

The reply was sent directly to Walker, meaning that only people who followed both men would have seen it in their timeline, but a man perusing WeRateDogs' mentions tweeted a screenshot of the exchange. That tweet has now been seen more than 35 million times, Nelson estimates. The Washington Post called "They're good dogs Brent" the best meme of 2016. The line has been appropriated by dozens of companies, sports teams, and universities looking to seem cool online. It also marks the most popular items in Nelson's shop—Brent items alone bring in thousands of dollars a month.

Walker told a Washington Post reporter his only intention was to make people laugh, but Nelson was genuinely offended. "It's like, the idea that the account is only cute dogs did touch every nerve," he tells me between holes on the golf course. "If it was just cute dogs I wouldn't have millions of followers. I work really hard on this to make the writing really good, so for him to say people only like it because of the photos did make me mad."

Yet he says he didn't put much thought into "they're good dogs, Brent" and didn't consider an angrier reply. Breaking character would puncture the world he's created, where the typical internet vitriol is replaced by doggos and puppers who are magical af.

Nelson has allowed the outside world to seep into WeRateDogs on just a handful of occasions. His most popular tweet of all time was a repost from a Toronto resident who took her golden retriever to that city's Women's March wearing a sandwich board with brightly colored letters spelling out "I march for my moms." While a few dozen Trump supporters replied with variations on "stick to dogs," and 800 people unfollowed him, the account gained 37,000 followers in the 24 hours after the tweet. "I march for my moms" has since been retweeted nearly 50,000 times and liked 134,000 times. Nelson, who identifies as liberal, later tweeted a photo of a dog reunited with its Iranian-American owner after a court struck down President Trump's travel ban, but he says he draws the line at anything explicitly partisan. "To me, those are more pro-human rights than they are political," he says. "If your views are against basic human rights, then I'm pretty sure I can say what I want and get support."

That's proven true for the most part. But with increased visibility inevitably comes increased criticism, even when the subject is dogs, and Nelson is still perfecting the tone to strike when someone calls him out. In March, he tweeted three photos of a corgi with an assistive device attached to its rear end to allow it to walk despite its paralyzed back legs. "This is Tycho. She just had new wheels installed. About to do a zoom. 0-60 in 2.4 seconds. 13/10 inspirational as h*ck," he wrote. The tweet touched a nerve with disability-rights advocates, many of whom object to words like "inspirational," saying they objectify and infantilize people simply living their lives. When a few followers criticized his word choice, Nelson's initial response was the written equivalent of an eye roll. "I give up," he wrote above one screengrab on his personal account. "... what is happening," he quote-tweeted another. Twenty minutes later, he changed course and tweeted an apology. "It was poorly thought out for reasons I'm still learning," he wrote.

In the early days of the account, Nelson's only goal was to make his jokes as funny as possible. Now that WeRateDogs is a brand, the calculus is more complicated. The bulk of Nelson's tweets are not as absurd as they once were, and more feel formulaic. Using an app called Twitter Engage, which is marketed toward celebrities and "influencers," he checks the account's analytics obsessively, trying to spot patterns among successful tweets and deleting ones he deems duds.

One of the first dog ratings I saw, three days after he started the account in November 2015, showed an intense-looking husky puppy sitting in the grass. "This is Joshwa. He is a fuckboy supreme. He clearly relies on owner but doesn't respect them. Dreamy eyes tho 11/10," Nelson wrote, a caption that would feel recognizable to members of Weird Twitter but unfamiliar to anyone who's followed the account more recently. A tweet from while I was visiting Campbell captured the new ethos: "Say hello to Boomer. He's a sandy pupper. Having a h*ckin blast. 12/10 would pet passionately," he wrote under a photo of a puppy on the beach. By swapping in a different adjective for "sandy," the caption could be substituted for a huge percentage of tweets in the WeRateDogs archive.

Nelson does miss the creative freedom he had before WeRateDogs began earning him an income that outstrips most working adults. In March, he started a new account, Thoughts of Dog, which he uses to tweet from the perspective of a dog character in a more absurd style. He doesn't intend to incorporate Thoughts of Dog into the larger brand; for the moment, it's replaced the main account as the side hobby that allows him to flex his humor-writing muscles with fewer constraints.

"WeRateDogs is a little bit less fun now because I feel restricted as to what I can say," he tells me."For me it's not like, 'Wow, I just made a fantastic caption for this picture,' It's just a post that's going to do okay. Obviously I wouldn't want to stop doing this, so once it seems like all the captions are repeating themselves, then I'll just focus that creative energy in other places."

Andy Warhol once said, "Being good in business is the most fascinating kind of art. Making money is art and working is art and good business is the best art." These days, running WeRateDogs is much more about the art of good business, and Nelson has come to love that, too. He tweets as WeRateDogs twice a day, each of which takes between a few minutes and an hour. The rest of the time, he's overseeing the brand: evaluating social-media analytics, figuring out how to split up the month's profits, responding to a never-ending stream of emails. He delegates some tasks to two part-time employees: John, a recent University of Pennsylvania grad, sifts through the roughly 1,200 photos submitted by fans each day and sends Nelson roughly 20 of the best candidates for ratings; Tyler, who graduates this month from high school in Missouri, oversees the online store. Each is paid a small commission on each item sold through the shop.

Nelson also has become a vocal opponent of online joke theft. After an anonymous Twitter user made a series of false copyright complaints against WeRateDogs in February 2016, getting the account temporarily shut down, a professional agent volunteered via direct message to help make sure Twitter wouldn't suspend him again. Since then, Nelson has made a point of calling out people who repost his tweets without attribution, often in funny and profane ways.

Nelson's dad, Mark, the executive director of a Charleston law firm, provides the actual business experience, helping his son figure out how to trademark his language, divide revenue, and invest his share. "I keep reminding him of professional athletes that don't graduate and they get $10 million contracts and in three years they can't play their sport of choice and all their money is gone because it's either been stolen or they've mismanaged it—not that Matt's in that league with that income," Mark said. "But to date, he has not touched a dime of any revenue as a result of WeRateDogs."

Nelson has plans to increase that revenue: more merchandise, new catchphrases, a recent update to the mobile game that he's so excited about he mentions it three times unprompted. He's working on his first major corporate partnership, which would pay him to take over the company's accounts for a day. For the moment, the world of doggos is full of promise.

But internet veterans know that memes and viral Twitter accounts don't tend to last forever. As Ryan Milner, a professor of media studies at College of Charleston who studies Internet culture, puts it: "Sign your book deals while ye may, because, absolutely, in six months will people be over this, will the jokes have run stale? Virality is a super-sharp spike and then it fades off." I think back to the lesson about product life cycles from Nelson's Principles of Marketing class. The professor's chart showed an upside-down "U," culminating in a decline in popularity. She did not discuss exceptions.

When I ask Nelson whether he's considered the possibility of a dropoff, he answers immediately, as if brushing away a pesky mosquito. "I think I have the edge in that no one's going to stop liking dogs anytime soon. Twitter could die, but the people that love the writing, the people that follow me, are going to find me in other places if Twitter dies."

Late one evening a few weeks after my trip to Campbell, Nelson tweets a bombshell from his personal account: "WeRateDogs needs a change." He follows up immediately: "not a big change calm down" but waits forty minutes before explaining further: "It's too predictable. I'll try to do some refreshing things & stay a little bit more true to what I think is well developed creative content." When I ask about his thinking in a text message, he says he wasn't intended to be a grand gesture, he just thought "a few tweets in a row seemed stale." The next day, a rare video post draws 61,000 likes, far above average, while the caption on a photo of the alien from the Disney film Lilo and Stitch nods back to the Weird Twitter-inspired early days of the account.

When the semester ends, Nelson makes a weeklong stop at his parents' house before heading to Philadelphia for a five-month golf internship that's required for graduation. But it seems increasingly likely that fulfilling his Professional Golf Management curriculum doesn't matter: He's planning to spend his free time this summer working on transfer applications to colleges with digital media programs. He's thinking about UCLA, Stanford, or USC—California seems like the place to be if you're trying to grow an audience, he's decided.

Though he has some great friends in the golf program, he won't be sad to leave Campbell, he tells me. He may be internet-famous, but almost no one on campus has any idea who he is. As he eats lunch in a quiet student center, talking openly about his book deal and his mobile-game deal and his thriving clothing line, no one approaches to ask if he is really WeRateDogs. He could have helped recruit students to this Baptist college in rural North Carolina if anyone had cared about his success. But no one does. "The only thing I owe to this school," he says, "is the boredom that caused me to start the account in the first place."

Sitting in the on-campus Starbucks after sorting through emails and the final March sales totals from the shop, Nelson turns his attention to dog photos. He hasn't put out an original tweet yet today, though he retweeted an old favorite while sitting in Principles of Marketing, and inspiration is coming slowly. John has already sorted through the day's thousand-plus DMs and texted him about forty screenshots (their text chain has so many photos that it crashes Nelson's iPhone's Messages app, so he can only open it on his laptop), but none seem to lend themselves to funny captions. He responds to a couple of people to ask for additional images, and briefly considers using a photo of a dog looking out a car's backseat window before passing because the pup is not in the driver's seat.

After about ten minutes, he finds a simple solution: two photos of a corgi wearing a shark costume, the pointed felt teeth hanging just above its eyes. "Not-dogs" are a staple of the account—whether through costume, camouflage, or just a vague resemblance to some other animal—and the tentpoles of the joke are the same each time. Nelson switches to his iPhone's Twitter app. He hovers over the screen for thirty seconds or so, circling his thumbs around each other, then types quickly: "Seriously guys? Again? We only rate dogs. Please stop submitting other things like this—" He pauses. He pulls up an online list of nationalities, a common tactic when looking for an adjective, discounting fraught possibilities ("I can't put 'Afghani') before changing his mind and going for a more general yet sillier approach. "... this super good hammerhead shark. Thank you. 12/10." he concludes.

It's hardly a comedic triumph by his standards, but a solid remixing of go-to elements. He predicts twenty thousand likes—not a home run, but not bad. At 8:13 pm, he posts the tweet, then heads back to his dorm to decompress for a while before bed.

By the next day the shark tweet has thirty thousand likes, right at the edge of his unofficial definition of viral. In his mentions, three other people have responded with photos of their dogs in the same costume. Several others don't have anything to say about the photo, just a plea for the new king of animal humor: "Please rate my dog!!!"

Photography by Jordan Wright.