Who needs Mandarin? Drive to succeed pushes Vietnam to bolster English curriculum

Despite improvements in standardised test scores, Vietnam’s weakest link continues to be its educational system, but government directives suggest a renewed focus on English that could unleash a manufacturing dynamo

Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City are equal parts exhilarating and exhausting.

It’s as if, after 30 years of war and deprivation, the Vietnamese are determined to make the best of life. A will to succeed at all costs separates Vietnam from the other countries in the region. People in the original “Asean Five” nations have already gone through that burst of explosive economic growth.

Policymakers will point out that while the Vietnamese are ruthless competitors, the country’s soft infrastructure, most notably its education system, remains “light years” behind the rest of Asean.

However, recent surveys – most notably the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s 2016 Programme for International Student Assessment (or Pisa) – show that Vietnamese teenagers have eclipsed their regional counterparts and are now consistently outperforming their American and British equivalents in mathematics and science.

Typically, Vietnamese benchmark themselves and their country against Taiwan, South Korea, China and Japan.

After talking to China about China, Vietnam goes to Washington to do it again

So while many may see Vietnam as an integral part of Southeast Asia, the Vietnamese themselves may not share the same point of view.

Of course, Vietnam’s position in the Pisa results is only part of the story. As with much of the rest of Southeast Asia, the local education system is riddled with flaws, most notably its obsession with rote learning and standardised tests.

A second major failing is that in an age of sweeping technological change, students need to be equipped to think creatively.

The tensions are self-evident, all the more so when one remembers that Vietnam remains – at least nominally – a communist state.

As the region’s governments struggle to anticipate future challenges, education policies are becoming a major test.

Most Southeast Asian parents (not to mention investors) see English as a global lingua franca and fluency in English enables students to aspire to an enormous range of job opportunities.

But unlike much of the rest of Asean, Mandarin isn’t seen as a critical language in Vietnam.

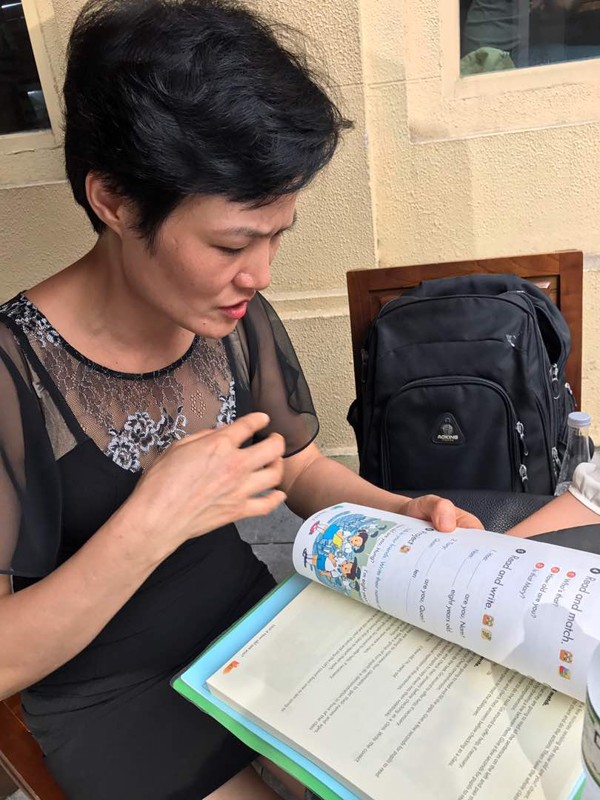

“Chinese? Why would we want to study Chinese?” said Dang Thi Doan Trang, 43, a lively English-language primary school teacher from a Hanoi suburb.

Trang’s devotion to English is infectious: “From the start, I loved the sound of English words. Of course, back when I was a student, I had to learn Russian but then in 1993 I was able to switch to English. I knew English was more important so I switched. Teaching English is my passion; I’m not doing this for the money.”

Trang – who has been at it for 19 years – is a contract teacher, not a civil servant. This means her salary, which varies from about 1,280 million Vietnamese dong (HK$438) to 4 million Vietnamese dong (HK$1,371) depending on the number of classes she teaches a semester, is lower than the average – and she won’t get a state pension when she retires.

What’s really behind Vietnam’s sacking of top Communist Party official?

However, she admits most teachers make a lucrative living providing classes on the side.

But that’s the least of her worries: “Classes are very crowded; there are 44 students in my class.There are four lessons in a week lasting 40 minutes. I don’t think that is enough… but I don’t have the time.

“Equal attention should be given to four skills: listening, speaking, reading and writing… [However] writing is, for the most part, ignored. The higher-ups say that the syllabus for primary students should only focus on listening and speaking. But the textbooks used are unsuitable; the proof is that the students can’t speak at all after studying.”

A key challenge is pronunciation: “It’s terrible, the students pronounce many words wrongly. When they enter secondary school and meet foreign teachers, they can’t utter a word. They can only speak well when they go for private lessons.The syllabus doesn’t answer realistic needs.

“Education bureaucrats simply impose the syllabus on students without knowing whether it suits them. I think they should come down to the schools more often.”

The World Bank reported in 2010 that the gross enrolment rate at upper-secondary schools in Vietnam was just 65 per cent, compared with 95 per cent in South Korea. Could Vietnam’s impressive Pisa scores simply be because many poor and disadvantaged students drop out of school?

But it’s not as if Vietnamese parents don’t care: “[There] are now many foreign firms coming to invest. They know that even factory workers need to know English. Parents are very eager about their children learning English. At my district, it’s like a movement. Everyone thinks that learning English is very important, not only in primary school but also at kindergarten.

“The pursuit of knowledge is like a tradition to us. Without a good education, their kids won’t get a good job in the future. [Unfortunately] the Ministry of Education never asks for parent’s feedback.”

To be fair, the Vietnamese government appears to recognise the challenges.

From war to peace and now prosperity in rural Vietnam

Education Minister Phung Xuan Nha has acknowledged that improving the quality of English teachers in the country is crucial, noting that: “It’s better not to learn at all than to learn from a bad teacher.”

So even though Vietnamese students are scoring well on the Pisa tests, the Ministry of Education is reviewing the all-important Project 2020 – a blueprint for national foreign-language teaching – which began in 2008 with a budget of 10 trillion Vietnamese dong.

Such an ability to shift gears to deliver improved results is what makes Vietnam such a formidable competitor. Their leaders are using the absence of democracy to implement necessary reforms and equip their people for the future.

While Trang feels a little disheartened by what she sees as a failing system, her criticisms are already shaping the future response to foreign-language teaching.

If the Vietnamese Education Ministry figures out how to implement the changes, we will likely see more factories relocating to what is fast-becoming Asean’s most dynamic manufacturing hub.