Guilt

The End of Guilt

Guilt bothering you? Or is it just shame because other people may find you out?

Posted June 6, 2017

Guilt and shame have been in the news this last few months. In January there was a report from a large team of psychologists centered at the University of Queensland in Australia and led by Matthew J. Hornsey. They argued that liberal-minded individuals like to say sorry much more frequently than conservatives. Liberals, you’d conclude, experience guilt a lot more frequently than their conservative neighbors. A few months later there was a weekend essay in the Wall Street Journal by Shelby Steele, The Exhaustion of American Liberalism, that said that white guilt gave us a mock politics based on the pretense of moral authority. Steele maintained, amongst other things, that that “white guilt is not angst over injustices suffered by others; it is the terror of being stigmatized with America’s old bigotries—racism, sexism, homophobia, and xenophobia.” I’m going to suggest that it’s not guilt at all that’s at issue. It’s shame. But should we care? I’ll explain why later—but first some definitions.

What is shame? One of the most helpful ways to understand the emotion is by looking at how it’s visualized. This recruiting picture from the First World War gives one very helpful example. The poster is trying to shame people into enlisting in the army. The father in the poster must have done no service at all. He stayed home with his children. The little girl with the adult’s face shames her father by asking him about his military service, “Daddy, what did you do in the Great War?” So does his little boy, who sits on the floor playing with a cannon and with soldiers. He’s doing a child’s version of what his father should have been doing in the Great War. I guess that the Parliamentary Recruiting Committee is saying in this poster: “watch out or you’ll be shamed by your family just like this cowardly sap—join up!”

To feel shame, there has to be someone who will out you for your bad behavior. That’s the little girl in this picture. You can’t feel shame if your bad behavior is known only to you. Most people can’t feel shame unless someone can see their shame.

What sort of behavior counts as shameful? It results from an unjustified claim on something or on someone that is not rightly yours for the taking or for the enjoying. Staying put in that armchair while others are copping a bullet in the trenches for King and Country is just such an instance.

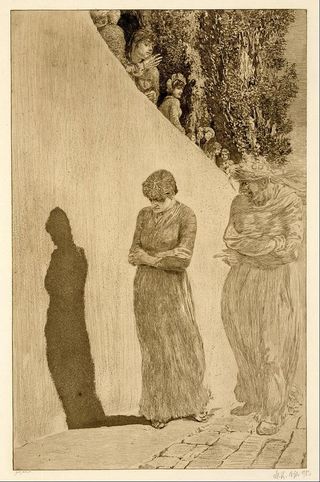

You can paint or represent shame more easily than you might expect. Here’s one more image that shows how. Shame’s an emotion that, as far as I can tell, usually requires three visible elements. You need a perpetrator (the first element: the woman in the center of Max Klinger’s picture, or the father, in the recruitment poster), you need an individual or a group of individuals outing the perpetrator (the second element: this is the older woman to the right of the picture, or the little girl in the poster), and you need some sort of an audience (the third element: this is the group of women staring down from at the top of the wall, or, in the recruitment poster, the little boy). There has to have been something that the perpetrator has done or is said to have done to create the hoo-hah. But we don’t always know or even need to know what the shameful deed was. Klinger’s version of shame is powerful precisely because we haven't got a clue what the woman has done.

What about guilt? The term “guilt” is often used as a synonym for “shame.” I don’t want to adjudicate English usage and say that you can’t use the words as synonyms. But, traditionally, the words describe different emotions.

Guilt’s an emotion you’re supposed to feel because you’ve caused harm in some way or another person. Guilt also “follows directly from the thought that you are responsible for someone else’s misfortune,” explains Susan Krauss Whitbourne. She also suggests that guilt may occur when “a person believes or realizes—accurately or not—that he or she has compromised his or her own standards of conduct or has violated a universal moral standard and bears significant responsibility for that violation.”

It’s as easy as this to say what guilt is. But it’s very difficult to find images representing the emotion. If you think I’m making this up try to Google “guilt” and ask for “images.” You’ll quickly see what I mean. Most of the representations that you will find could be better understood as evocations of grief or even depression. The reason for this is simple enough. Guilt comes from within and it feels bad. But to show guilt, you need to do more than just to show people feeling bad.

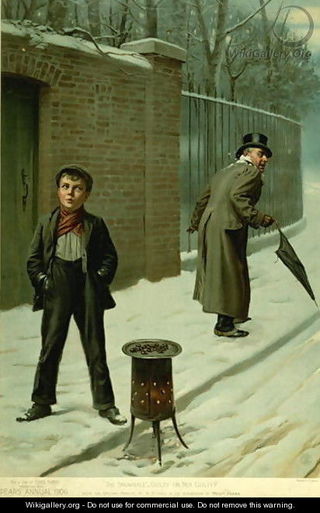

Here’s one amusing attempt to display guilt. But it’s one offering a more realistic version of the emotion than you’d expect. The boy is selling chestnuts. He’s just lobbed a snowball at the toff in the top right of the painting. You can see the snowball on the man’s neck. The picture appeared in the yearly Christmas annual published by the soap maker, A & F Pears (from 1891 until 1926). The annual had as its main theme Christmas illustrations and stories. Pittard's popular painting, from the 1906 issue, is a soapy Christmas illustration of innocent guilt.

Where is the guilt? The boy is trying to appear innocent, but who else could have thrown the snowball at the man’s back? The boy’s wary eyes are looking hard to his left in expectation that his victim might come back at him. His hands are deep in his pockets aiming to show that, no, he couldn’t possibly have thrown anything. His legs are spread to create an air of innocent nonchalance. None of these gestures convince us.

There are two thematic elements in the painting that highlight guilt. There are two people, a perpetrator (the boy) and someone who has been affected (here the toff) by the villainy. Guilt is built on doubles—shame is built on triples. The guilty perpetrator also needs to be waiting. Shame happens right now. Guilt is all about waiting for a future punishment. That’s caught very well in the eyes of the boy.

But once the event that causes the guilt is over and done and past, you can’t see guilt. This may seem silly. Think of it like this. I can only know that you’re feeling guilty if you tell me. If I ask you, “Are you feeling guilty?” and you reply, “Yes, I am feeling guilty,” I can only be sure it’s the case if you can describe your emotion in such a way that it matches the definitions of guilt that we’ve just seen. I mean to say, you couldn’t reply “I’m feeling guilty” if you answer the question “How do you know you’re feeling guilty?” with “Because I feel really happy.” Perhaps that’s why there are so few successful images of guilt. It’s why guilt, unlike shame, is so very hard to diagnose. It’s also why we need to be cautious how we use Matthew Hornsey’s and Shelby Steele’s conclusions.

It’s shame, not guilt. In Matthew Hornsey’s picture the liberal seems to apologize to avoid suffering the disapproval of fellow liberals and, in turn, the condemnation of others. The conservative holds their apologetic tongue and does not apologize for the same reasons. What would their ideological neighbors think? And Shelby Steele? For the liberal, according to his diagnosis, the fear is of incurring the disapproval of others by being responsible for misaffirming one or the other of his markers of “white guilt”—political correctness, identity politics, environmental orthodoxy, the diversity cult and so on. The situation that he invokes is like that of the father in the recruitment poster. Misaffirmation will lead to being denounced by other liberals and in turn to condemnation by still others. It’s all about “threes” for Hornsey and Steele. And that’s shame.

Should we care? Maybe we should because these may all be signs of the end of guilt. The hey-day of guilt lasted from the Christianization of Rome until some time in the middle of the 20th century. In literature it had an even shorter life span, perhaps from Dostoyevsky to John Steinbeck. Guilt has never made much of an impression on visual art. Last year Andy Crouch, the executive editor of Christianity Today, and then David Brooks, the New York Times columnist, reckoned that guilt had been supplanted by shame as a marker of American culture. Maybe. Or maybe guilt never was very important in the first place. Maybe that’s why it has always been so hard to visualize.

June 7, 2017