The first time Scottish concert promoter Andi Lothian booked the Beatles, in the frozen January of 1963, only 15 people showed up. The next time he brought them north of the border, to Glasgow Odeon on 5 October, they had scored a No 1 album and three No 1 singles, and it was as if a hurricane had blown into town.

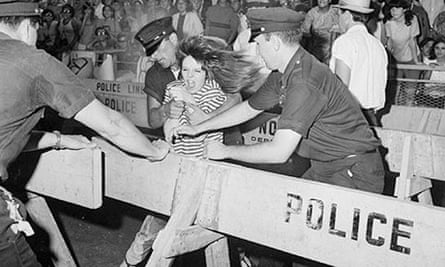

The night almost unravelled when nervous local police insisted Lothian bring the Beatles on early to satisfy rowdily impatient fans, even though his bouncers were still in the pub. "The girls were beginning to overwhelm us," remembers Lothian, now 73 and a business consultant. "I saw one of them almost getting to Ringo's drumkit and then I saw 40 drunk bouncers tearing down the aisles. It was like the Relief of Mafeking! It was absolute pandemonium. Girls fainting, screaming, wet seats. The whole hall went into some kind of state, almost like collective hypnotism. I'd never seen anything like it."

A Radio Scotland reporter turned to Lothian and gasped, "For God's sake Andi, what's happening?" Thinking on his feet, the promoter replied, "Don't worry, it's only… Beatlemania."

The coinage is usually attributed to a Daily Mirror story about the Beatles' London Palladium concert eight days later but Lothian insists it came from him, via Radio Scotland. Either way, the phenomenon predated the label. Throughout 1963 there had been reports of teenage girls screaming, crying, fainting and chasing the band down the street; police escorts were already required. But catchy new words have a magical power in the media. Once it caught on, it seemed to cement the phenomenon in the collective imagination.

Although pop fandom has since become more complex and more self-documenting (few Beatles fans had cameras), the tropes of Beatlemania have recurred in fan crazes from the Bay City Rollers to Bros, East 17 to One Direction: the screaming, the queuing, the waiting, the longing, the trophy-collecting, the craving for even the briefest contact. When One Direction's Niall Horan recently said of his group's fans: "They are nuts. Mostly all I see is a sea of screaming faces," he could have been any boy-band star from the past 50 years.

The novelist Linda Grant was a 12-year-old in Liverpool when she first heard Love Me Do. "Everybody was a Beatles fan in Liverpool," she remembers. "You just knew you were in the centre of the universe. I still feel that Cliff and Elvis fans were from an earlier generation even though there was only a couple of years in it. The Beatles belonged to every teenage girl. I feel like I was there at the birth of pop music. The Beatles are the Book of Genesis."

The media's attempts to explain this wild new development to bewildered adults were at best comically square ("Beatles Reaction Puzzles Even Psychologists," reported one science journal), and at worst viciously snobbish and misogynistic. In an infamous New Statesman essay Paul Johnson sneered: "Those who flock round the Beatles, who scream themselves into hysteria, whose vacant faces flicker over the TV screen, are the least fortunate of their generation, the dull, the idle, the failures."

Teenage girl fans are still patronised by the press today. As Grant says, "Teenage girls are perceived as a mindless horde: one huge, undifferentiated emerging hormone." In an influential 1992 essay, Fandom as Pathology, US academic Joli Jensen observed: "Fandom is seen as a psychological symptom of a presumed social dysfunction… Once fans are characterised as a deviant, they can be treated as disreputable, even dangerous 'others'."

"Lots of different fans are seen as strange," says Dr Ruth Deller, principal lecturer in media and communications at Sheffield Hallam University, who writes extensively about fan behaviour. "Some of that has to do with class: different pursuits are seen as more culturally valuable than others. Some of it has to do with gender. There's a whole range of cultural prejudices. One thing our society seems to value is moderation. Fandom represents excess and is therefore seen as negative."

Lothian can't remember why he chose the suffix "mania" but it carried a lot of historical baggage. It was first applied to fandom in 1844 when German poet and essayist Heinrich Heine coined the word Lisztomania to describe the "true madness, unheard of in the annals of furore" that broke out at concerts by the piano virtuoso Franz Liszt. The word had medical resonances and Heine considered various possible causes of the uproar, from the biological to the political, before deciding, prosaically, that it was probably just down to Liszt's exceptional talent, charisma and showmanship.

One Parisian concert review, quoted by Liszt scholar Dana Gooley, suggests the first stirrings of modern pop fandom: "The ecstatic audience, breathing deeply in its rapt enthusiasm, can no longer hold back its shouts of acclaim: they stamp unceasingly with their feet, producing a dull and persistent sound that is punctuated by isolated, involuntary screams." Lisztomania also had its Paul Johnsons. One writer in Berlin, where the phenomenon began in 1842, bemoaned the frenzy as "a depressing sign of the stupidity, the insensitivity, and the aesthetic emptiness of the public".

There were other celebrity "manias" in subsequent decades but no musical performer inspired the same intensity and media soul-searching as Liszt until Frank Sinatra began his residency at New York's Paramount theatre in October 1944. The so-called Columbus Day Riot, when thousands of teenage "bobby-soxers" rampaged through Times Square, inspired reporter Bruce Bliven to call it "a phenomenon of mass hysteria that is only seen two or three times in a century. You need to go back not merely to Lindbergh and Valentino to understand it, but to the dance madness that overtook some German villages in the middle ages, or to the Children's Crusade". Again, the behaviour sounds very familiar to the modern reader. One of Sinatra's publicists described how fans "squealed, howled, kissed his pictures with their lipsticked lips and kept him prisoner in his dressing room. It was wild, crazy, completely out of control."

So girls screamed at Sinatra, they screamed at Elvis, they even screamed at Cliff Richard. What made Beatlemania a fan frenzy of a different order? Of course, as with Liszt, the band's talent, charisma and showmanship were key, but two crucial extrinsic factors were timing and television.

The baby boom meant there were more teenagers than there had been for Elvis or Sinatra, with more money in their pockets, filled with a powerful sense that society was changing. To love the Beatles in 1963 was to embrace modernity. The critic Jon Savage, a 10-year-old fan at the time, recently wrote in Mojo: "It's fused in my memory of the 1960s starting… Big events were happening in the world, and pop was intimately connected to them. It wasn't just entertainment."

If you were a girl, especially one on the cusp of adolescence, Beatles fandom possessed an additional frisson. The critic Barbara Ehrenreich noted in a 1992 essay that while mainstream culture was increasingly sexualised (paging Philip Larkin), teenage girls were still expected to be paragons of purity. "To abandon control – to scream, faint, dash about in mobs – was, in form if not in conscious intent, to protest the sexual repressiveness, the rigid double standard of female teen culture," wrote Ehrenreich. "It was the first and most dramatic uprising of women's sexual revolution."

Londoner Bridget Kelly remembers her first Beatles concert, at the Finsbury Park Astoria on Boxing Day 1963, as the most important day of her young life. "It was something to do with being in a place between childhood and adulthood where you could let go and go mad. I would never dream of being cheeky to my parents so that was our little outlet."

To younger teenagers, the Beatles' cheerful, faintly androgynous sexuality was more approachable than Elvis's alpha-male heat: they wore suits and smiled and wanted to hold your hand. Best of all, there were four of them, each with his distinct appeal, so you could choose which one reflected your own preferences and desires. "For reasons that are beyond me I liked Ringo," says Linda Grant. "There was a real goody two-shoes at school who liked Paul. George seemed a bit nothing. John seemed off-limits, too intimidating."

"All the girls talked about marrying their favourite Beatle and I think that terrified our parents," says Linda Ihle, who was a 13-year-old Paul fan living in Long Island, New York. "It was very sexualised. We weren't at the age yet when we were permitted to date. We liked boys but boys were still a bit less mature than girls. These were young men but they seemed very attainable in some way. They were adorable, they were different, they were irreverent and our parents didn't approve of them, which made it even better. Boys tended not to like them as much. I think they were intimidated by the fact the girls were so attracted to these young men."

Reading this on mobile? Click here to watch video

Thanks to television, fans knew in advance exactly what was expected of them. The Beatles Come to Town, a Pathé newsreel recorded in Manchester in November 1963, was practically a how-to video, depicting a sea of howling, tear-stained faces wearing a curious expression best described, by Tom Wolfe, as "rapturous agony", and producing a high, relentless wail, like a hormonal alarm clock. "When they come to your town, well, you won't need any further invitation: you'll be there," said the plummy announcer.

For American fans, the Beatles' appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show in February 1964, to an audience of 73 million already primed by press hype, was an advertisement for Beatlemania as much as for the band. "Seeing them on The Ed Sullivan Show, with the girls screaming in the audience, it was contagious," says Ihle. "That, coupled with news reports of girls screaming at the airport, spurred it on."

It was the noise that mademost impression on contemporary observers, who called the fans "screamers" and wondered why anyone would want to drown out their favourite band's music. And it was the noise, eventually, that prompted the Beatles to retire from live performance in 1966. "I never felt people came to hear our show," Ringo later grumbled. "I felt they came to see us."

They also came to see one another. When Paul Johnson wrote, "The teenager comes not to hear but to participate in a ritual," he meant it as an insult but it certainly was a ritual. Although stereotyped as brainwashed consumers, the fans were far from passive. They loved the music, of course, but they'd heard these songs a thousand times. When they screamed they were also celebrating themselves, their freedom, their youth, their power. Screaming didn't drown out the performance: it was a performance.

"You soaked up energy from the crowd," says Ihle, who attended the band's first Shea Stadium show in 1965. "The screaming never stopped. We could barely hear the music because the sound systems weren't very good back then. There were police everywhere, trying to keep fans from jumping on to the field. It was a happening, to use a word from the time. It was the event itself. It was being there."

"I didn't understand why you had to scream and I didn't have an impulse to scream but it was what you did," says Linda Grant. "It was mandatory. There was this cult-like element to it."

All the fans I spoke to mentioned the sense of solidarity and group identity. "Sexuality is only a small part of fandom," says Ruth Deller. "The writer Susan Clerc says the most primal instinct of the fan is to talk to other fans and I think there's something in that. The idea of community and collectivity is important."

"It makes you feel like part of something larger," says Ihle. "You're not by yourself. Individually, teenagers are isolated and worried and scared all the time of whether or not they're doing the right things and wearing the right clothes, but everybody liked the Beatles so everybody was equal. It didn't matter what your clothes were or where your parents worked; we were all in it together."

The most devoted fans wanted more than concerts. They craved encounters and artefacts. Ihle still owns one of the blank pieces of paper that rained down on fans waiting outside the band's New York hotel one day in 1964. "If they'd touched it, we wanted it," she says. This is one of fandom's oldest traditions. During the first outbreak of Lisztomania, newspapers reported that female fans collected not just locks of their idol's hair but his piano strings, cigar butts and coffee dregs.

Jan Myers, a Londoner who is writing a book about her experiences as a hardcore Beatles fan, went to extraordinary lengths. She bunked off school to cycle 20 miles to Heathrow to greet the band's flight. She crawled through the sewers under Abbey Road to hear them recording Rubber Soul through the floorboards. She even gatecrashed the Yellow Submarine after-party. "We did crazy things," she says. "We were fanatical. We could stand outside Abbey Road for 16 hours and as long as one of them came and smiled or said something it was fine. But my mum would rather I was doing that than stealing or popping pills. I didn't smoke, I didn't drink, I was just obsessed. All I could think about was them."

The scale of Beatlemania caught the band by surprise. When Myers secured her first autograph from Paul in early 1963 he was still in the habit of signing his name "Paul McCartney (The Beatles)", as if an explanation were necessary. Later, she noticed them becoming more defensive. "Paul would say, 'Oh God, not you again,' but he was the best at talking with the fans. John was very unpredictable. You had to be careful with John. But when you're a fan you let them say whatever they want. You were happy he'd talked to you directly, it didn't matter what the words were." She sighs. "How pathetic is that?"

Puzzled, unnerved and occasionally terrified by their fans, bands employed poachers turned gamekeepers to handle them, such as Beatles fanclub secretary Freda Kelly, the subject of a new documentary Good Ol' Freda, and Shirley Arnold, who did the same job for the Rolling Stones. "When I first went I was more interested in working for the Stones, and then I realised that I was working for the fans," Arnold told writer Stanley Booth. "I was a screamer, that's why I understood the fans."

For a long time, it seemed that only fans had the ability, or even the desire, to understand other fans. They were viewed as either hysterical mobs to be patronised or, especially after the murder of John Lennon, obsessive loners to be feared. But in the late 1980s and early 90s, a number of writers, including Jensen and Ehrenreich, began looking at fans with a sympathetic eye. Fan studies is now a fertile field of academia, while pop stars such as Justin Bieber and Lady Gaga are increasingly canny about managing their fans. But at the same time, fans' high profile on social media, where a trending topic can lead the casual observer down a rabbit hole of bewildering intensity, has inspired a new wave of adult angst. "A scorned Directioner is a terrifying beast," remarked one TV critic reviewing a recent documentary Crazy About One Direction.

"The fundamentals are largely the same: people looking for community and identity and developing taste and sexuality," says Ruth Deller. "And moral panics about fandom have been with us for an awfully long time. But the internet has definitely made fandom more visible – for those participating in it but also for everybody else."

If anyone is likely to look kindly on the excesses of new generations of fans, it's a former Beatlemaniac. "I understand when I see the One Direction kids going mad," says Bridget Kelly. "People think they're silly but they're not. It's the togetherness. We had this big communal thing that we all knew and loved and understood — something that was yours and nothing to do with your mum and dad. We were all in it together. It was lovely."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion