Picture this. It’s a Saturday morning, and autumn sunshine is falling through the blinds. You have a cup of coffee, a book, and an easy chair. Best of all: you’re alone. Your family, housemates, spouse, or children are elsewhere, and three uninterrupted hours stretch before you.

Restful, right? For introverts, who—goes one popular definition—gain energy by spending time alone, gathering their thoughts and regrouping emotionally, solitude is the obvious choice when it comes to resting.

But a new study into the state of rest has found that for most people, activities done alone—including simple solitude itself—are the best ways to rest. And that includes extroverts who, according to the same definition, tend to gain energy by being with others.

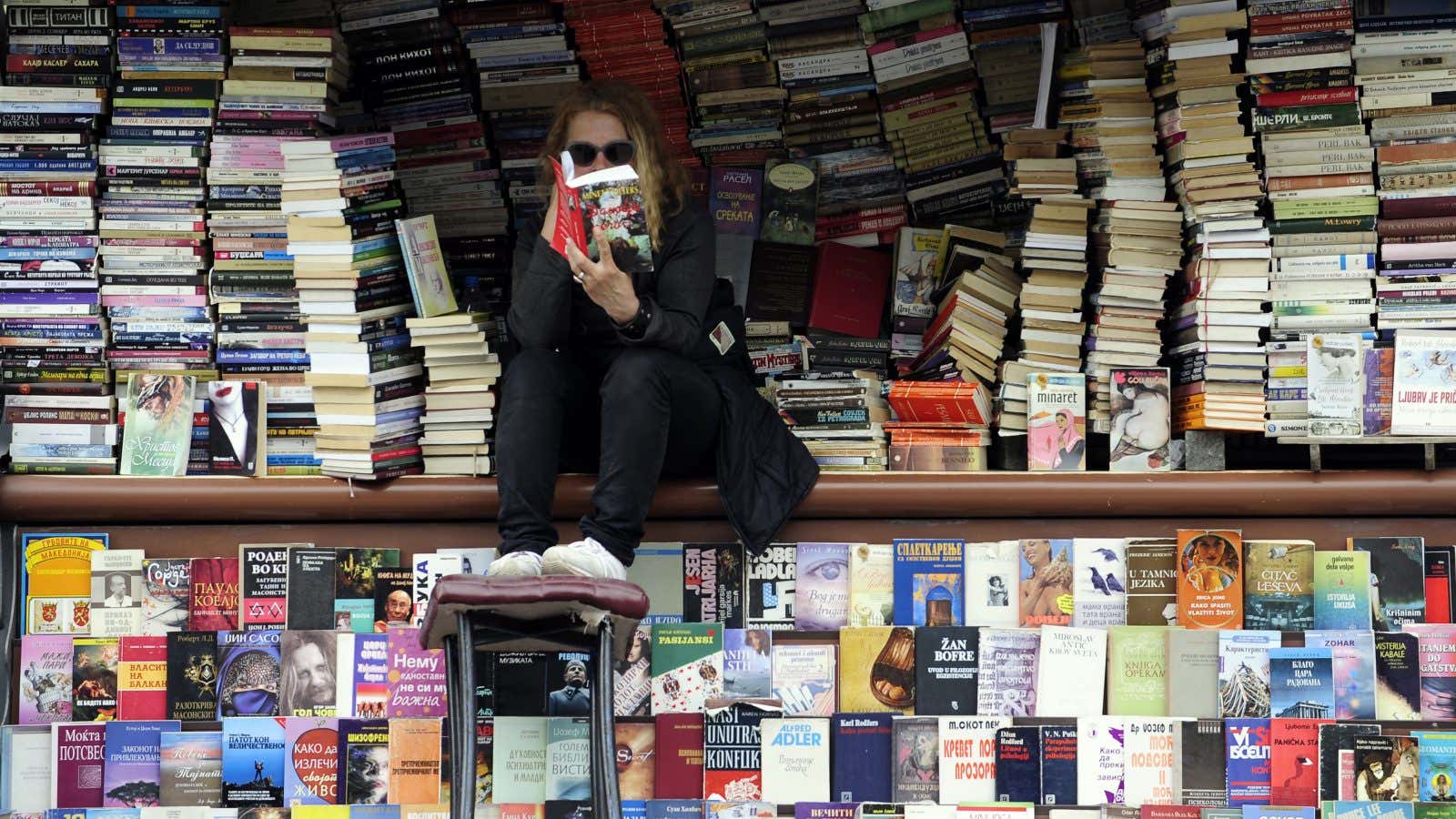

Reading was the most restful activity cited by the 18,000 people who filled out an online survey which the researchers, funded by Wellcome, a large health-focused charity, said was the biggest study run on rest to date. Second came being “in the natural environment,” followed by being alone, then listening to music, then ”doing nothing in particular.”

“The analysis team was struck by the observation that a significant number of the top ten restful activities chosen by participants are often carried out alone,” the researchers wrote in their preliminary findings. “It’s interesting to note that social activities including seeing friends and family, or drinking socially, placed lower in the rankings. It’s also not just introverts who rate being alone as a restful activity. Extroverts also value time spent alone, and voted this pastime as more restful than being in the company of other people.”

The study was carried out by the BBC in conjunction with researchers from a number of universities and disciplines, including cognitive neuroscience and anthropology, and involved an online survey filled out by 18,000 people in 134 countries. Felicity Callard, a professor of social science at the University of Durham, who directs the research group, said that the second part of the survey used a psychological scale to work out where people placed themselves on the introvert/extrovert axes, as well as how happy they were.

She said that the hectic nature of modern life has primed us to be very interested in how to rest. “The discourse of busyness is everywhere,” she said. “That sense of boasting, or status coming from being incredibly busy and productive. At the same time people think it’s unsustainable, but rest seems like this unattainable thing.”

One of the most interesting findings, Callard said, was that many people don’t think of work and rest as opposites. Studying those people could give insights to businesses that could help limit stress and stop burnout. While it’s unlikely that work could ever become purely restful, she said, future research will explore ways for the brain to get more of what it needs without so much strife: “How might we organize the rhythms of work to allow rest to become more possible within it?”