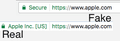

Here’s a challenge for you: you click on a link in your email, and find yourself at the website https://аррӏе.com. Your browser shows the green padlock icon, confirming it’s a secure connection; and it says “Secure” next to it, for added reassurance. And yet, you’ve been phished. Do you know how?

The answer is in that URL. It may look like it reads “apple”, but that’s actually a bunch of Cyrillic characters: A, Er, Er, Palochka, Ie. The security certificate is real enough, but all it confirms is that you have a secure connection to аррӏе.com – which tells you nothing about whether you’re connected to a legitimate site or not.

The proof-of-concept domain was put together by Xudong Zheng, a security researcher who wanted to demonstrate the problem with the way domain names can be registered and displayed. For a long time, domain names could only be written in Latin characters without diacritics, but since 1998 it’s actually been possible to write them in other alphabets too. That’s useful if you want to register a domain name in Chinese or Arabic script, or even just correctly spelled French or German – anything that can be represented with the Unicode standard can be registered, even emoji – but it’s also opened up a whole new avenue of misdirection for malicious actors to take advantage of, by finding characters in other alphabets which look similar to Latin ones.

“From a security perspective, Unicode domains can be problematic because many Unicode characters are difficult to distinguish from common ASCII characters,” Zheng writes. “It is possible to register domains such as ‘xn--pple-43d.com’, which is equivalent to ‘аpple.com’. It may not be obvious at first glance, but ‘аpple.com’ uses the Cyrillic ‘а’ (U+0430) rather than the ASCII “a” (U+0041). This is known as a homograph attack.”

Some browsers will keep an eye out for such tricks, and display the underlying domain name if they sense mischief. A common approach is to reject any domain name containing multiple alphabets. But that doesn’t work if the whole thing is written in the same alphabet.

Apple’s Safari and Microsoft’s Edge both still spot that Zheng’s spoof domain is a fraud, but Google Chrome and Mozilla Firefox don’t, instead displaying the Cyrillic domain name. And though it may be obvious in the Guardian’s font that something’s up, the sans serif typeface used as standard by those browsers leave the two indistinguishable.

Zheng says: “This bug was reported to Chrome and Firefox on January 20, 2017…The Chrome team has since decided to include the fix in Chrome 58, which should be available around April 25.” Mozilla, however, declined to fix it, arguing that it’s Apple’s problem to solve: “it is sadly the responsibility of domain owners to check for whole-script homographs and register them”. Google didn’t comment beyond referring to Zheng’s blogpost, and Mozilla didn’t comment at publication time but a spokesperson later said: “We continue to investigate ways to further address visual spoofing attacks, which are complex to fix with technology just in the browser alone.”

Itsik Mantin, director of security research at Imperva, said that common advice to web users falls down when such simple attacks work. “In order to protect website users, forcing them to use strong passwords and to replace them frequently is insufficient, since in this case it would be completely ineffective to prevent the attack.

Instead, he said, a better approach begins by assuming that phishing attacks will succeed: “Site administrators should assume that the credentials of some of their users were stolen (which in almost 100% of the cases will be true), and take adequate measures to identify account takeover, like irregular device, irregular geo-location or abnormal activity in the account.”

Zheng himself offers advice to users: use a password manager, and try and spot phishing attacks before you click on any links. “In general, users must be very careful and pay attention to the URL when entering personal information. Until this is fixed, users should manually type the URL or navigate to the site via a search engine when in doubt.”