In the half light on a quiet street on the edge of west Philadelphia, Kristal Bush shut her front door and hustled down her stone steps. She crossed the street and climbed into the driver’s seat of her shiny, black 12-passenger Sprinter van. Juggling two phones, she turned the key. The engine chugged awake, and she started tapping out texts to her riders. A few minutes shy of 6am on a summer Sunday, Kristal was already late.

About six years ago, when Kristal was 22, she and her mother, Crystal Speaks, decided to try their hands at turning circumstance into opportunity. Crystal was going broke from the expense of the visits to see her son, Jarvae. He was serving a 10-year sentence in Huntingdon state prison, 200 miles from Philadelphia. Opportunity came in the form of thousands of Philadelphia families like theirs who have someone locked up far from home.

In the years Jarvae was at Huntingdon, Crystal got to know some of the other regulars well enough to start giving them rides. She’d pick them up from their homes twice a month in her white Nissan Armada. They’d pay her $50 for her gas and her trouble. It was just $5 or $10 more than the bus a local not-for-profit group offered, but they had to meet the bus in downtown Philly before daybreak. What Crystal didn’t spend on the trip she’d put on Jarvae’s commissary account, easing the prison’s bite into the paycheck she brought working long hours as a nurse’s aide.

One day in the visiting room, Jarvae looked around at the women his mom had driven there that day. “Jarvae said, ‘Man, there’s a lot of people coming up here, you should turn this into a van service,’” Crystal remembered. Jarvae called his sister Kristal and leaned on her to help make it happen. On that bumpy road of carceral enterprise, Bridging the Gap LLC rolled to life.

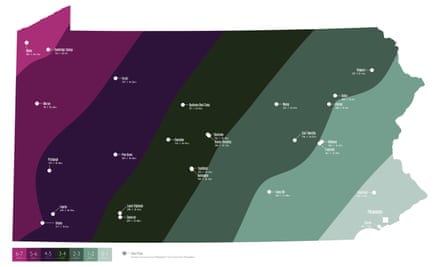

About 49,000 people live behind the walls of Pennsylvania’s 26 state prisons. Many of those facilities sit in rural counties deep into central Pennsylvania, where incarceration is among the most robust and lasting employers. But most of the prisoners come from Pennsylvania’s cities – above all, Philadelphia.

The state doesn’t keep numbers on prisoners’ hometowns, but it does track whwhich courts send them. About 28% of Pennsylvania state prisoners were sentenced in Philly, according to an analysis of the state data by Columbia University’s Brown Institute for Media Innovation. Of them, about half are in a prison more than three hours’ drive from Philadelphia.

A prison is a prison is a prison, some might say. But to the loved ones trying to maintain ties, miles make a difference. To get to prison, one must also have disposable income. To get inside, one cannot have spent time behind bars. In the neighborhoods Kristal’s vans sweep through to pick up customers, the twin punches of poverty and mass incarceration have winnowed the visiting population. Those left, Kristal’s customers, are nearly all working women.

There is an impression that those in prison live on the taxpayer’s dollar. To some extent, it’s true: Pennsylvania spends more than $2bn each year on corrections; nearly $300m goes to prisoners’ education, training and healthcare. But more than $1bn of those dollars go to paying off the debt on buildings, and to the salaries and retirement benefits of employees, many of them in rural counties where the state opened prisons to blunt the pain of factories shuttered.

As the national cost of locking people up ballooned to over $80bn a year, Pennsylvania joined systems across the country in snipping expenses where they could. Cuts came to food, laundry and healthcare. Prisons closed. Commissary prices rose.

There is, said sociologist Megan Comfort, at least a tacit acknowledgement by correctional institutions that when they cut back, families will cover the difference. Even a woman struggling to make ends meet on minimum wage can more quickly afford the $3.09 for a six-pack of boxer shorts than can a prisoner earning 50 cents an hour in a facility kitchen.

“Women on the outside are really making prisons run,” said Comfort, senior research sociologist at the non-profit Research Triangle Institute International, who studies prisons’ impact on families. “Their labor and their economic power has been folded into the way the institutions are working.” That holds back many of the women working hardest to rise. “All their money starts to go into the criminal justice system to support the men in their lives,” Comfort added.

Day broke just before Kristal stopped to pick up two women from a brick duplex. Ms Rachel rocked from side to side toward the van, moving uncomfortably with her cane. Her body’s visible aches fell short of the deeper ones that had, since the sentencing of her grandson Jeff, dragged on her soul. Jeff’s girlfriend, Lois, 28, held their 18-month-old daughter Jade on her hip.

Lois’s son, Cameren, had meant to come too, before his fire fizzled with the early morning alarm. Though not blood-related, Cameren considered Jeff a father. The four-hour trip each way felt like a lifetime to a seven-year-old boy, and that morning, when Lois woke him, Cameren shook his head and turned back to bed.

There are moments when Lois wanted to climb in beside Cameren, to cancel on Kristal, to avoid the reality of Jeff’s 20-to-40-year sentence. Kristal lets kids as young as Jade ride for free. Even so, Lois thought about what else she could do with the $50 she pays Kristal for her seat. “It’s just like, do I put this toward this bill or do I take Jade up there?” she’d ask herself each time she got her paycheck from the non-profit she worked for downtown.

Going with Ms Rachel eased some of the burden. Jade’s great-grandmother helped when the baby fussed on the ride. She paid for the visiting room food. Between them, Jeff and Jade could eat six packets of microwaved chicken wings. That cost her $24. The sodas were $2 each. Chips were $1, then they’d both ask for candy. Lois ticked off that menu when Jeff called her asking when she’d come next. “I try to explain to him that coming up there to visit you, that’s a $100 trip,” she said.

Lois had goals. Upgrade her associate’s degree to a bachelor’s. Put in the required hours for her Habitat for Humanity house, where the monthly mortgage would buy a permanence that rent didn’t. Ms Rachel knew Lois, not even 30 yet, also dreamed of a man beside her life. But she promised both herself and Jeff that would never get in the way of Jade knowing her father.

“She’s a good girl,” Ms Rachel would say before voicing her doubt that Lois would stick out Jeff’s whole sentence. Given the growing number of amber pill bottles clustered on her bedside table, Ms Rachel didn’t know if she could either. The thought that Jeff might do those decades alone weighed on her weak heart.

Kristal held Ms Rachel’s elbow as she hoisted herself into the vehicle. Three generations of women arranged themselves in the van’s seats. Kristal slid the door shut; she had five more stops to go.

Kristal was terrible with names, but she remembered each rider’s story. In most, she heard echoes of her own.

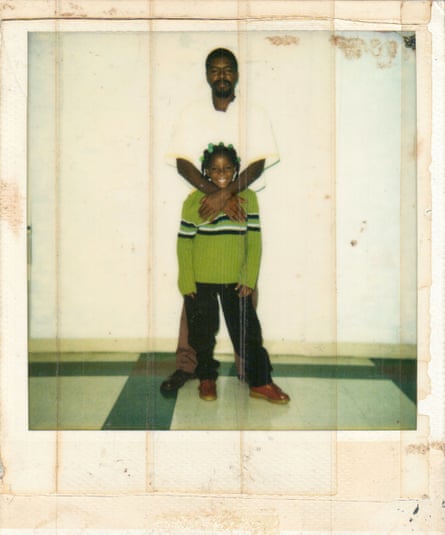

When she was three, Kristal’s father was sent to a prison five hours from Philly. She saw him only a handful of times before she turned 18. Jarvae was in and out of lockups starting when he was a teenager. Her older brother, Gerald, also did time. She had cousins serving life. “Even when I was younger with my best friend it was like, ‘Hey girl, your dad locked up? Oh mine’s, too!’” she said. “It was just so normal to me.”

But driving people to prison wasn’t the career Kristal envisioned for herself. If her brother Jarvae used his ambition to earn “fast money” in the streets, Kristal put hers toward distancing herself from them. At the charter high school she went to, teachers insisted everyone apply to college. She forged her mother’s signature on the paperwork and made her way to Temple University. After she graduated, she used savings scrimped from her student loans for a down payment on a house. It was close enough to the hood to still be affordable, and far enough to feel like she was making it.

A full-time job as a social worker covered both her mortgage and the first Bridging the Gap van that she bought for her mother down at the local auction. That’s where Kristal thought her role in the business would end. “I didn’t want nothing to do with prisons,” she said. But she was pragmatic. When her mother began to lose interest in driving, tiring from long stretches on the road, Kristal took over so that money she spent on the van didn’t go to waste.

She took it on with the rigor of any good millennial entrepreneur. She posted pictures and videos on Instagram and Snapchat; then came an app for easy scheduling and a deal for half off your fifth ride. Incarcerated friends and relatives passed the word around the prison yard, drawing in more riders. She bought a second van, then a third. Crystal started driving again, this time as her daughter’s employee, making runs to prison in between night shifts as a cleaner at a cancer clinic.

The company grew, but Kristal had loftier goals. “Whatever I do, I always gotta find a purpose behind it,” she said. She put that purpose on T-shirts, bags and the side of her vans, in script: “Bridging the Gap: bridging the gap between inmates and their loved ones.”

The sun was already hot when Kristal pulled into the gas station on the edge of the city to meet Crystal, who was driving a second van to the prisons in Huntington County that day.

Riders got out to stretch their legs. Erica sauntered over to join the other ride-or-die regulars. Her bob was fresh and a flowered dress wrapped her curves. Next to her, Tysheen, Aisha and Tanesha stood in a circle, their long khimars rippling in the hot air. “My sisters looking good today,” said Erica, a pastor’s daughter taking in the elegance of her three Muslim friends. They smiled. The four women had become close riding the van, cliquing up, introducing their kids, sometimes staying over at one another’s houses on the night before a ride to give opinions on makeup and outfits.

Aisha leaned in to look at the shoebox in Erica’s arms. “All Stars,” Erica said. Every week, Erica tried to wear something new for her fiance, Maurice, keeping her outfits as fresh as the bright white shoes in the box. Each woman had her tricks to compensate for all the intimacies denied.

On the road, prison rides settled into a rhythm. Early miles were for small talk; the hours through the rolling green mountains, for sleep. A half-hour from the prison, the women began to stir. Anxiety and excitement buzzed underneath the R&B streaming over the speakers. On a busy Sunday, late arrivals might be relegated to sitting outside in the heat if the visiting room was too full. Or worse, they might be turned away.

Lois pulled out her comb and began to twist sections of Jade’s hair, clipping a barrette to each end. Tysheen spritzed herself with scent. Erica flipped her camera to selfie mode and fluffed her hair. Aisha pulled out a compact and swept gloss over her full lips. She pulled out towelettes, then passed them around so everyone could clean their palms and under their fingernails. Pennsylvania prisons swab the hands of all visitors for drugs. Even touching dirty money can get a visit denied.

“Make sure y’all don’t have no wire or nothing in your bra. They may be searching the vans to be prepared to have y’all’s stuff checked. If you all have anything, we can roll down the window, open the door and let whatever you all have out.” Here Kristal would pause each week, hoping it wouldn’t come to that. Then she’d smile. “Other than that, enjoy your visit!”

Tanesha didn’t even wait for Kristal to stop before pulling the van door open. She took off, black khimar billowing behind her, forgetting the bum leg that had recently kept her homebound. Tysheen, in gray, was just behind. It was 10.30 am. There was no time to waste.

Riders sorted, Kristal pulled into her favorite spot in the parking lot to wait out the five-hour visit. She liked to look out over the green valley she found both peaceful and a little eerie. Crystal parked the second van beside her. She rolled down the window to tell Kristal how her riders had bolted out of the vans toward the prison doors.

“They always running – Tanesha the main one, talking about, oh my leg hurts!” said Kristal. She shook her head. “I can’t tell, not the way you running into that prison!”

Mother and daughter cracked up. “They’s crazy,” said Kristal. “I love them though.”

Around the same time that Kristal took over the van service, she found out her brother Jarvae’s son, Nyvae, who had lived with his mother outside the city, was on the verge of going into the foster care system.

Barely out of college, Kristal became her nephew’s official guardian. Prison took away her father, along with most of the other men in her life. Then it turned her from aunt to mother. She swore to herself it wouldn’t make her a wife. But like her riders, Kristal found bonds hard to break.

Kristal had laid herself out to rest in the back seat when the phone rang. She answered the call from Khali.

Kristal met Khali through her hairdresser in the beginning of 2012. They hit it off, and moved in together fast. But after he was indicted on drug conspiracy charges in late 2013, their romance morphed into a deep friendship. Khali was facing a life sentence for dealing pain pills. Like Lois, Kristal imagined more of a life partnership than could fit in a prison visiting room. But he was still the person she talked about family with, and the one she consulted as she tried to figure out how to raise Nyvae into the man she wanted him to be. Khali’s dad had been in prison when he was a kid. His grandmother was the one who insisted he make his bed and take out the garbage, chores he said Nyvae should do to balance out all the ways Kristal spoiled him.

In the tender bluntness of their prison-monitored conversations, Kristal found a relationship of equals. Khali was her confidant and her cheerleader. “When they’re in prison,” Kristal said, “they see a different side of us because they see how strong we are.”

There are, according to an analysis by the New York Times, about 36,000 black men “missing” from Philadelphia, lost largely to early death or to prison. Only New York and Chicago, cities much larger than Philly, have more men gone. The women who ride Kristal’s van, the majority of whom are black, have had at least one man go missing in the Philadelphia prison system. Most have seen violence take several more away. Compounded loss makes for brutal decisions, the kind that can break a woman’s heart.

At 3pm, Kristal pulled out to retrieve her riders. On the road, women exchanged “How was your visits?” The consensus, this week, was good. Some days Kristal sees tears, fuming, disappointment deep enough to bring visits to a skidding halt. Good visits made for better rides home. Women cracked their armor.

Deep in a conversation about the importance of education with Ms Rachel, Erica hunted around in her phone until she found the photo of her nine-year-old daughter Faith’s report card. She pinched the image big so the older women could see.

“Wow, look at them A’s!” cooed Ms Rachel. “Praise God.”

Erica swiped again until she found photos of Faith’s second-place win at the science fair and scholar of the week certificate.

“And you in north Philly?” Ms Rachel asked, knowing what it meant to grow up in the city’s most troubled quadrant. “She got a challenge and still beat the odds.”

Nodding, Erica produced a video of Faith’s violin concert, music lessons another amenity that had convinced Erica to bus her child the county over from Philly. “When she started going there, the teacher said I see what part of the city you living in,” Erica told Ms Rachel. “She said your daughter speak so well.”

Erica had already taught Faith how to smooth and sterilize sentences so people would look past her address, her father’s absence, the color of her skin. When Faith said, “Mom, I’m either going to be a doctor or an RN, I’m not aiming for nothing else,” Erica told her, “You can do it.” It’s what she told herself on the mornings where she didn’t know if she could do another 17-hour shift caring for her disabled clients, or on the nights she went home again to an empty bed.

Knowing that all 6 feet 5 inches of Maurice would be waiting at the prison fence when she pulled up kept her riding. But doubling down on love exacted a price higher than the $400 a month Erica spent on visits, $200 twice a month for commissary, and phone calls that ran to $75 a week. She wanted to go back to school, but between work, raising Faith and the trips to Huntingdon, her ambition got pushed to the back of the line.

“Your life is on pause however long you decide to stay with this individual or until this individual comes home,” she said. “That’s why some people do walk away.”

Sixteen hours after she pulled away that morning, Kristal arrived home. At the end of some of these trips, Kristal thought about giving up on the company. Each time she got close, the phone would ring, and she’d think: darn, I can’t leave these people. She walked through her door, collapsed on the couch, and scrolled blankly through her social media feeds. Soon she’d start sending texts to riders about the next day’s trip. They expected her there.

Eight months later, one of Kristal’s vans arrived to pick up Erica and Faith. Erica had recently gotten the news that Maurice, who is serving a four-to-eight-year sentence, had been denied parole. She had been telling Maurice that she was done waiting – another “hit” from the parole board and she’d walk. Instead, she decided to double down again. What she hadn’t done was told Faith; Maurice wanted to do it as a family.

Erica reserved two seats on Kristal’s van for 11 March. She and Faith woke before dawn to make that 200-mile drive to the visiting room at Huntingdon where Maurice waited for them, trying to figure out how to tell his daughter that daddy’s not yet coming home.

This project was supported by the Economic Hardship Reporting Project