A world-leading Chinese ceramics collection and the feud that tore it, and a family, apart

The finest collection of 17th-century Chinese pots in the world has been broken up after a bitter battle that split the family of late British diplomat Michael Butler, the man who amassed it. Two of his children tell their side of the story

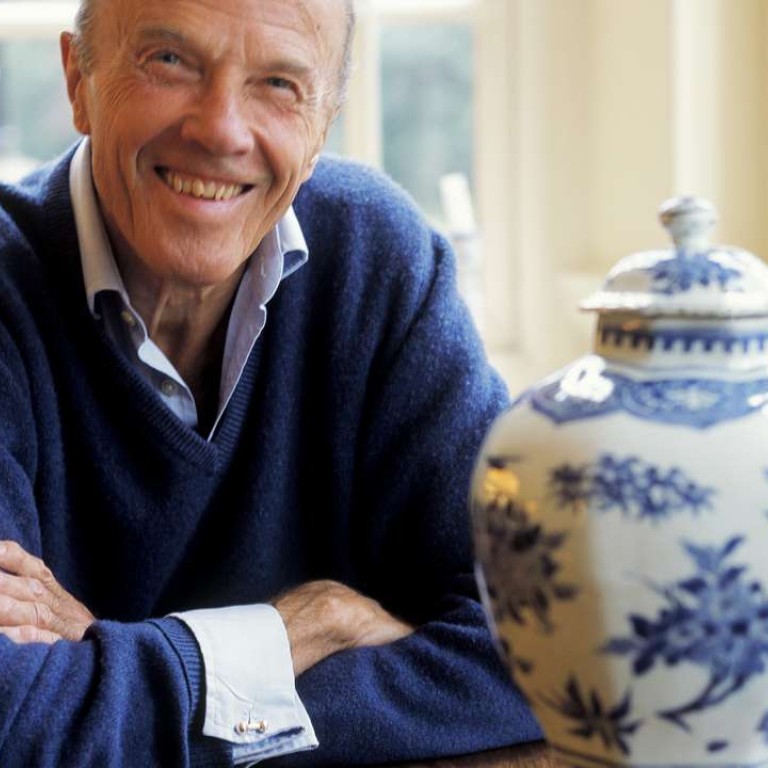

It all started with some empty shelves. In 1960, Michael Butler, a diplomat at the British Foreign Office, was in search of ornaments to fill the white space in his house in London’s Chelsea. He decided to follow his collector friends to Sotheby’s, where he bought a box containing what were described as “six old pieces of Chinese porcelain” – among them a small 17th-century apple-green wine pot, complete with fine bamboo-shaped handles, which stole his heart.

From that moment on, he spent as many weekends as he could “pot hunting” and, over the course of almost 60 years, amassed a priceless hoard of 850 pieces that made up, by most expert accounts, the finest collection of 17th-century Chinese ceramics ever assembled.

In the 1980s, wanting his four children, Caroline, James, Charles and Katharine, to take up the porcelain mantle – and with a little efficient tax planning thrown in – Butler passed on 502 of his late Ming and early Qing pots to the next generation in a series of gifts, with each child owning a quarter share.

By the turn of the 21st century, Butler had retired as a diplomat, having served as Britain’s permanent representative to the European Commission and as a key adviser to prime minister Margaret Thatcher. He began to feel guilty that his most prized possessions were being stored in an old tool shed behind his grand house in Mapperton, in Dorset, southwest England. So Butler commissioned an architect to extend a barn in his back garden (used as a squash court) into a 500-square-metre, seven-room museum.

Sitting holding that very first green pot (bought for £15, now worth tens of thousands), his youngest child, Katharine, is still trying to fathom how this fabulous inheritance has shattered her family into pieces.

There had been signs of what Butler’s wife and mother to his children, Ann Ross Skinner, euphemistically describes as the “troubles” that lay in store for the family. Tentative arguments about the The Butler Family Collection (now thought to be worth at least £8 million (HK$75.5 million) began with the globetrotting civil servant’s separation from Ann in 1997, following revelations about his adultery. Eldest child Caroline had – in Katharine’s words – “a rather strong reaction”, and her father began to lose faith that she would respect his wishes to keep the collection intact.

I’m not sure you ever come to terms with the fact that your own father does not love you and prefers 800 pots

He stopped directly passing the pieces on to his children, instead inviting the four to join a partnership that controlled the ungifted pots – on the condition that the entire collection be preserved for at least 10 years after his death. The elder two, Caroline and James, declined the offer.

Butler died on Christmas Eve, 2013, at the age of 86. Charles and Katharine received the first legal letter from their brother and sister a month after the funeral.

“We counted up that we had tried over 30 times in different methods to sit down and talk,” says Katharine, 49. But every attempt was rebuffed.

While the elder pair wanted what was legally theirs – a quarter of the pots each – the younger two were determined to do everything to stop what they saw as “cultural vandalism” and guard their father’s legacy. The letters soon became “a barrage”.

“We couldn’t believe it,” Katharine says. “Sometimes we got two or three in one day.”

The case brought by Caroline, 64, and James, 51, ended up in London’s High Court last year, where the family’s secrets spilled out for all to see. Charles and Katharine’s barrister claimed that, after finding out about her father’s infidelities, Caroline had sent letters to his colleagues spreading the news – which Butler believed had cost him a place in the House of Lords, the upper house of Britain’s parliament – something Caroline dismissed as “spin by Charles”.

An e-mail she had sent to Katharine shortly before their father’s death was read out in court. It said: “I’m not sure you ever come to terms with the fact that your own father does not love you and prefers 800 pots. You can have no idea what this means because he loves you and sees in you his mother whom he loved above all things.”

The verdict came down to an obscure chunk of property law dating back to 1925.

“There is no family as dysfunctional as ours in the history of English law,” Charles, 50, quipped to me shortly after the judge’s verdict was handed down, as he explained that the only precedent was a case from the 1950s involving a family disputing the division of a three-piece suite.

Katharine and Charles – who have each made their own fortunes by setting up various businesses in the Czech Republic – were adamant that the court had to take into account the cultural value of the collection. But Judge Simon Barker QC came down on the side of the older siblings; under the law, half of the pots belonged to Caroline and James, who were entitled to do what they liked with them.

British tabloid the Daily Mail illustrated its report on the story with a cartoon showing two women in a pub discussing the case. “I’ve fallen out with my husband over our Ming collection” – says one to the other – “We haven’t got one.”

It neatly summed up how many readers would have reacted to the saga while enjoying their cornflakes: if only we had a multimillion-pound pottery hoard to wage war over.

However, Katharine – and countless experts – are clear that this is about much more than just a family driven potty by their squabble over heirlooms.

“There is no other collection on the planet which can illustrate with such clarity the vicissitudes and re-emergence of a major Chinese industry,” says Colin Sheaf, global head of Asian art at Bonhams.

To rebuild a collection like this now would be impossible

According to John Ayers, former keeper of Far Eastern art at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A), the pots “represent a unique Western contribution” to the history of China’s major art form.

Chen Kelun, deputy director of the Shanghai Museum, warns that “to rebuild a collection like this now would be impossible”.

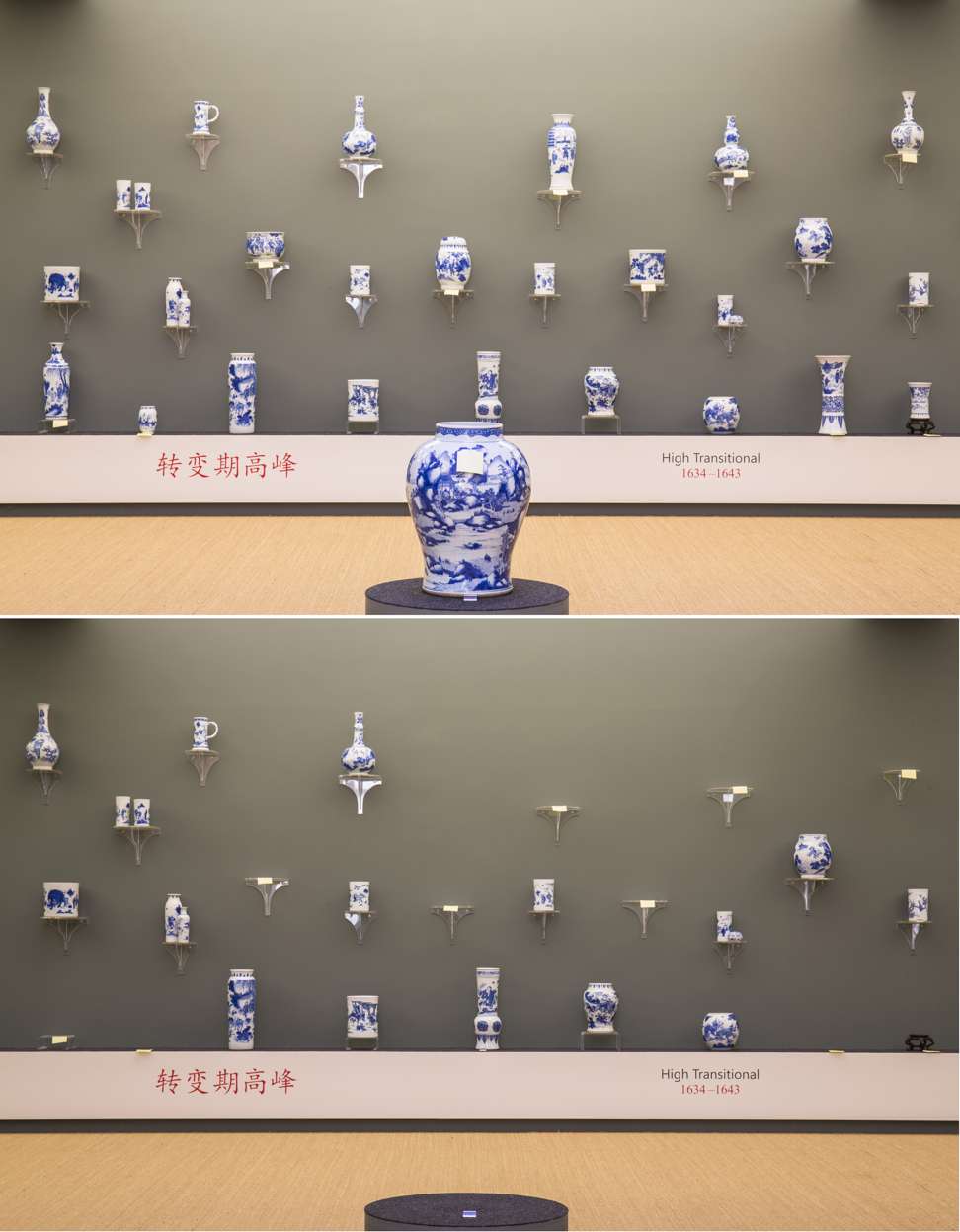

The last imperial kiln closed in the porcelain capital of Jingdezhen, in Jiangxi province, in 1608, after the Ming dynasty had run out of money as a result of civil war. For 75 years, before the imperial kilns reopened and with no regular and rigid orders from the court, highly skilled potters and painters were forced to find new customers – in the form of merchants, the literati and export markets – triggering an explosion of innovation.

“They created a whole new style, which was incredibly experimental and they had new shapes and new decorations and new political stories on the pots,” Katharine enthuses. “It was a total renaissance.”

However, until Butler came along, the period had been seen as a deeply unfashionable no-man’s land for collectors and museums, who had only ever valued imperial wares made for the palace as being of high quality. This meant that not only could he afford items from the so-called Transitional Period, but he could also play porcelain explorer in uncharted territory. As Katharine says: “It was really a kind of open field that Pa stepped into.” He unearthed new styles, redated pieces that had been miscatalogued and, in his spare time, slowly managed to become a world-renowned expert – The Man Who Put The 17th Century On The Map.

When, in 1979, the Oriental Ceramic Society of Hong Kong was planning the first major exhibition of 17th-century porcelain, it came to Butler. He recalled in a video filmed shortly before his death: “When they arrived, they looked round and said, ‘Well, we didn’t know any of these things existed!’ And they put into the exhibition about 30 of my pieces.”

In 2005, he was invited to collaborate on an unprecedented exhibition by the Shanghai Museum – its first joint venture with a Westerner. Butler co-authored the catalogue, gave the keynote speech and lent some of the show’s most important exhibits. The exhibition was seen by almost 250,000 visitors in four months, before being taken to the V&A.

“That really established the 17th century as an important period in the Chinese mind,” says Katharine.

“He was greeted as a hero,” says Charles. “I went with him. They took him down to their store room – and he told them what was good and what wasn’t.” The collection has also travelled to 13 museums in the United States.

The Butler stardust has not worn off. A memorial exhibition has just been staged in Jingdezhen and, on May 2, Professor Peter Lam Yip-keung, of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, will be delivering the Sir Michael Butler Memorial Lecture at London’s Oriental Ceramic Society.

Although imperial pieces still command higher prices at auction, Butler’s achievements in popularising porcelain from the period are thought to have almost certainly contributed to the boom in 17th-century fakes coming on to the market. This, Katharine says, is yet another reason why the collection was so crucial, becoming a surprising part of the English tourist map for many Chinese porcelain fans. It was built before the forgeries predominated and its scale meant it had a “library effect”, allowing visitors the chance to glean enough knowledge to distinguish the knock-offs.

Hui Tang first heard about Butler’s pots in 2005 while studying at Fudan University, in Shanghai, and fell in love with them when she came across a catalogue in a Paris bookshop. She was working towards a PhD in the Chinese porcelain trade with the East India Company, at the University of Warwick, in Britain, last year when she made the six-hour round trip to become the last visitor to see the collection before it was broken up.

“The space is so beautiful,” she recalls, when we speak on the phone, “open with natural light. And they don’t have any glass cabinets so you can actually handle any objects you like. The collection itself is without words – nothing can be compared with it. From this single collection, you can learn the whole period of that history.”

Although Butler’s place in the firmament of revered collectors is secure, other aspects of his legacy have not been so durable.

Never assume your children are going to behave like normal human beings

“My father’s two big projects for his life were Britain’s place in the European Union and his Chinese porcelain collection,” says Charles, “both of which, strangely enough, have been entirely trashed in the last few months.” The Brexit referendum, which is taking Britain out of the EU, came less than a month before the judge ordered the dispersal of his life’s work.

Over five torturous days in September last year, the four siblings – who had communicated with each other since their bereavement only through lawyers and glowering looks across a courtroom – reunited inside the museum. They took it in turns to select an item each until the 502 pots had been distributed, in a process Katharine has described as “the most devastating moment of my life”.

Amid the agony, there was a fleeting episode of levity when Caroline opted for a plate depicting the story of Dong Yong, a fable of “filial piety” – the Confucian virtue of respect for one’s parents. After explaining the irony of the selection, Katharine says, she offered her sister the chance to pick again (Caroline stuck with her choice).

With the amount of anger that our older sister has shown, I think it was a revenge on our father ... I do think there is a genuine element of wanting to wreck what he created

The second blinding irony is that the children of a man who was famed as an arch negotiator – who managed to secure Britain’s 1984 EU budget rebate, which is still mostly in effect and currently saves the nation about £5 billion a year – have been so incapable of compromise that they have racked up £1 million in lawyers’ fees between them (the younger two have been ordered to pay 80 per cent of the costs). That is not to mention the capital gains tax – possibly another several hundred thousand pounds – that all four will have to pay as the dividing of the collection is a “taxable event”.

And paradox number three: Caroline, a leading investment adviser, is a trustee of the Art Fund, which runs high-profile public appeals “to save works of art or collections” for the nation.

She and James, a financial consultant, have not made any public comment outside court, and their lawyer did not respond to our request for one for this article.

When I ask Charles and Katharine how and why exactly it came to this, I get a mixture of bewildered silence and an outpouring of hypotheses. In summation, they believe: 1. Caroline was unhappy about how the rest of their father’s inheritance was allocated (“Well, if the inheritance wasn’t fair, why take it out on the pots?” asks an incredulous Katharine); 2. Caroline objected to her younger siblings having been chosen as their father’s executors; 3. She was still smarting about the affairs; 4. She wanted the pots so she could sell them.

“At the beginning, we were pretty baffled,” says Charles. “We’re not on this earth that long, anyway, so there’s no point destroying things which have a cultural value for other people also in the future.

“With time, and with the amount of anger that our older sister has shown, I think it was a revenge on our father – for him not trusting her or not appreciating her as much as he should have. That was her motivation. And undoubtedly financial, for both her and my brother.

“And then the final thing, I do think there is a genuine element of wanting to wreck what he created. If a writer’s immortality is from their writing, our father’s immortality might partly have been because of this great cultural work.”

Katharine says of her sister, “I think that there’s all those different stages of grief and I really believe she got stuck in the angry phase.” Charles interjects: “Yeah! I think she’s been there for a while.”

“I had a good relationship with her and I had a very good relationship with James,” Katharine reflects mournfully. But she thinks much of the recent family breakdown inevitably harks back to childhood. “I think the basis of relationships in families is that you’re always somehow remembering the time when you were fighting over who had a bigger teddy bear,” she muses, “and it’s that memory of your very childish jealousies that will always have an impact on your relationships with your siblings.”

Charles butts in with a sudden recollection about how Caroline had related to her much younger siblings: “She used to call us ‘the larvae’. That was her name for us!”

Caroline and James said in court that they wanted their pots so they could display them in their own homes, but their siblings are far from convinced.

“I have a very large house,” says Katharine (who lives in the 17th-century, eight-bedroom, five-bathroom, two-swimming pool Waterston Manor, the inspiration for Weatherbury Farm in Thomas Hardy’s Far from the Madding Crowd). “And I couldn’t fit anything like 125 pots in this house – unless you want to stack them supermarket-style. Nobody has room, unless they live at Blenheim [Palace] ... and it’s empty.”

The older pair have consistently refused to give the younger two first refusal on buying any pots they put up for sale, even at full market rate. When I ask what it will take for any kind of rapprochement, Charles says, “I hope they’d think, ‘We’ve got our way, we’ve proved our point, they’ve had to spend a fortune, so why not find the bigness in our hearts to at least sell them some of the pieces?’ There are about 20 whose loss really damages the collection. That’s step one.

“I think it’s a forlorn hope, to tell you the truth.”

Either way, Katharine says, they plan to reopen the museum next year, and adds: “It would be great to have it travelling to China again.”

And then there is the small question of their own inheritance planning. “We need to do something about that,” admits Charles, otherwise his two children “will be having round two!”

The casualties of the fallout from it all are numerous, not least the siblings’ 87-year-old mother. Caroline and James no longer speak to Ann, after she backed Charles and Katharine’s battle to protect the pots, sitting loyally alongside them in court, working at her embroidery.

“They think I’ve taken sides and I’ve been brainwashed so there’s no point having any contact with me,” Ann says in the breezy, stiff-upper-lip way you can rely on a member of Britain’s upper classes to muster, as she stands in what was once a beautifully ordered museum – now in disarray. “Well, it’s an absolute disaster. It’s awful! I haven’t any words really strong enough. Despite being a dreadful expense, too. A hideous expense!”

Does she have a message for her two eldest? She says without hesitation, “No, I’ve said everything and they know perfectly well what I think, so I think there’s nothing more to be said.”

The former Lady Butler does, however, have some hard-earned advice for others passing on an estate. “Yes, make a trust! Don’t leave it to any member of the family! That’s the thing – when there’s money involved.”

And don’t assume your children will be sensible enough to sort it out when you’re gone?

She lets out a resigned laugh. “Neverassume your children are going to behave like normal human beings!”