Children’s books should be soft and fluffy things, perhaps with moments of discomfort or fear – lessons must be learned, after all – but always resolved with a happy ending. And entirely asexual. Right? Well, no, not really. Children’s books shouldn’t always be happy and simply aren’t asexual, just as children aren’t asexual – which is not to say that children are sexual in the way that adults are, but that sexual orientation and gender identity becomes apparent to many people early in life. Just as a straight child may pretend to marry her dolls to one another, or may have a crush on his big sister’s friends, a queer child may experience crushes, pair up their dolls differently or express their gender in a way that is different from the sex they were assigned at birth.

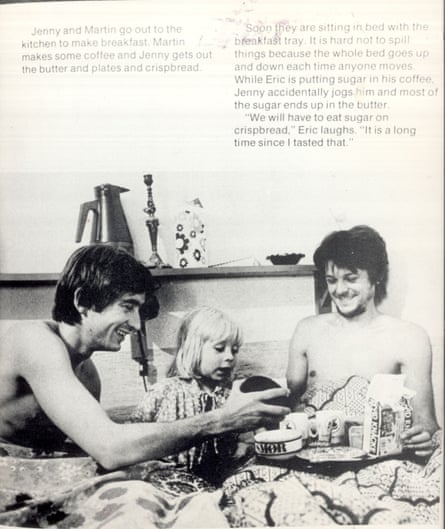

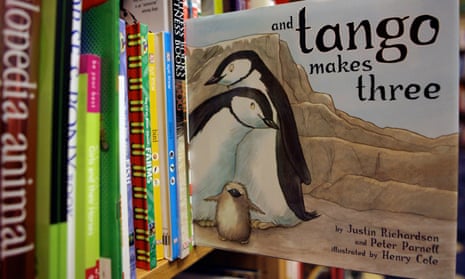

Covert nods to varying sexual orientations and gender identities have long been disguised in children’s books, but in recent decades, challenges to heteronormativity have been more overt. The now-famous book about two penguin dads, And Tango Makes Three, by Justin Richardson and Peter Parnell, caused quite a stir when it was published: it topped the American Library Association’s list of challenged books in 2007, 2008, 2009, and reappeared again in 2011. But as far back as 1981, Jenny Lives With Eric and Martin by Suzanne Bösche was depicting queer family life for small children, establishing a precedent for a long line of books that followed: Daddy’s Roommate by Michael Willhoite, Molly’s Family by Nancy Garden (of Annie on My Mind fame), 10,000 Dresses by Marcus Ewert and Rex Ray, Large Fears by Myles Johnson and Kendrick Daye. The 1990s and 2000s saw a huge leap in queer visibility in books for older children such as George by Alex Gino, and the works of Juno Dawson and David Levithan.

But we shouldn’t ignore the subtexts that have long been present in many children’s books, whether intentionally or not. They may been born from stereotypes, but as academic Jessica Kander writes, queer characters “can be recognisable to readers through the use of culturally and historically significant markers” – so, for example, depictions of butch girls and tomboys can be read as queer women. The two famous female Georges – Nancy Drew’s best friend and the intrepid member of The Famous Five – are tomboys and so have widely been interpreted as queer by readers and academics alike. Another example is Elizabeth Levy’s Something Queer Is Going On, whose heroines Gwen and Jill (not Jack and Jill, you’ll notice) are best friends. But the subtext is not so subtexty here: queer has, for almost a century, meant homosexual and Levy, who also wrote an expressly lesbian romance novel for teens called Come Out Smiling, was clearly not above sticking overt references in her titles.

Other girls adopted as lesbian icons have included Caddie – of Caddie Woodlawn by Carol Ryrie Brink – Pippi Longstocking and Harriet the Spy. None of them fulfils the heteronormative expectation of girlhood, especially for their times. Pippi, with her super-strength and brusqueness, first appeared on the page in 1945, while Caddie, a stark contrast to her traditionally feminine cousin, appeared in 1936 (and the book was set in the 1860s).

There is no mention of Harriet’s sexuality or identity beyond her self-identification as a writer and a spy. But Louise Fitzhugh’s book is historically beloved by lesbians, who saw their own uncomfortable childhoods in Harriet: the girl who dislikes dresses, doesn’t want to learn to dance, whose best friends are a baseball-loving boy and a mad-scientist girl, and whose differences end up pushing her away from the other kids who don’t understand her. Fitzhugh herself was a lesbian, who purportedly went by the name Willie within the lesbian community, so in Harriet’s case we have an almost certain depiction of a queer child, intended for children.

There are children’s books about queer male characters as well, though the interpretation is not as obvious and could be argued against more easily. Many, if not all, of the implied-queer male characters tend to be animals, an easy way to depict gentleness and softness in men (whether meant to be queer or not) without inviting criticism. The Story of Ferdinand by Munro Leaf is a good example: Ferdinand, a bull – a symbol of masculine virility if there ever was one – who doesn’t want to butt heads with the others. Preferring to sit in the meadow and smell the flowers, he’s carted off to the bullfights where he refuses to participate – and is finally put to pasture, where he can once again enjoy the flowers. Ferdinand’s story may resonate with boys who also dislike sporty, often violent heteronormative activities. “Bachelor types” often pop up in furry forms; think Ratty and Mole in the Wind in the Willows (Alan Bennett even threw in a few jokes about male bonding in his stage adaptation) or Pooh and Piglet (who even cohabit in The House at Pooh Corner).

But why animals? Researchers have found that children’s literature often anthropomorphises animals to “soften the didactic tone and ease tensions raised by dealing with issues not yet fully resolved or socially controversial”. But where lesbians have been alternately ignored, fetishised or dismissed as harmless flirtations, gay men have been controversial since the days of the Old Testament; discomfort at gay male characters or perceived common traits makes anthropomorphism almost inevitable.

Gone are the days of needing to disguise queerness in furry layers. In recent years, as young-adult literature has taken to fiercely tackling issues that teenagers face themselves – rape, abuse, eating disorders, bullying and more – it seems the need to hide queer characters from the prying gazes of adults desperate to shield their children has somewhat dissipated. More and more books have been published directly depicting queer relationships and varying gender identities for young and teen readers: Philip Pullman’s gay angels Baruch and Balthamos in His Dark Materials; 10-year-old Harold Hutchins in Captain Underpants; Patrick in the YA modern classic The Perks of Being a Wallflower.

And none of the above is to suggest that these books deal with sexuality in the way that adults see it. But these characters and narratives can shine a light into the corners of possibility for children searching for signs that they are not alone in their otherness.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion