7 Top Tips For Supporting Citizen Driven Community Building – Part 2

This week’s blog is the second in a series of seven top tips for supporting citizen-driven community building. The seven top tips for supporting citizen-driven community building are:

1. Find a trusted local association with sufficient infrastructure to act as host of the work, including hosting a paid Community Animator and partnering with an initiating group of local residents.

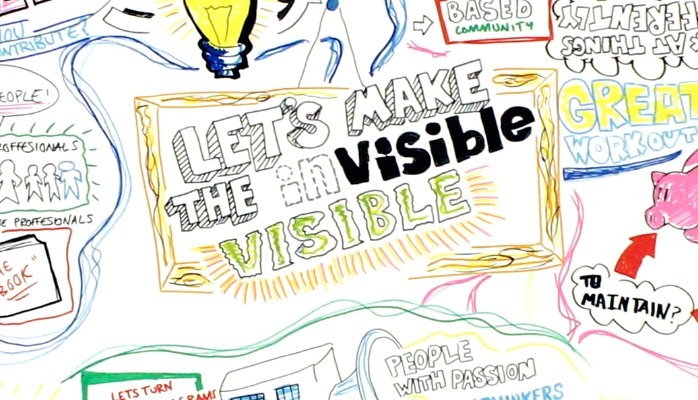

2. Start by making the invisible visible; don’t be helpful be interested.

3. Effective community building goes at the speed of trust, not a funding cycle or an election cycle. It’s messy, slow and real. Generations, decades, not years.

4. Start with what’s strong to address what’s wrong and make what’s strong stronger.

5. Community connectors are critical.

6. The optimum population size of a neighbourhood is 3,000 to 5,000 residents.

7. The focus is on growing a culture of community not converting people to Asset-Based Community Development (ABCD).

Tip #2: Start by making the invisible visible; don’t be helpful be interested

This week we’ll build upon the premise that local residents can’t know what they need from outside their neighbourhoods, until they first know what they have locally. We’ll also briefly explore the importance of identifying, connecting and mobilising the existing capacities of a place, by supporting citizens to create connectedness and build collective efficacy.

A sea of potential: dive in.

Each and every neighbourhood is bustling with activity, resources and capacities, albeit these often go unrecognised. Like a river’s undercurrent, they’re not immediately apparent unless you go swimming. Low-income communities of place all too often are viewed as backwaters of pathology, with nothing but needs and deficits, where helping professions spend a considerable amount of time fishing for what’s missing, rather than surfacing the underlying pool of potential.

But what if helpers stopped searching for what was wrong as their starting point and instead of being helpful, started being genuinely curious. What if the professional map was set-aside in preference for spending time unearthing hidden treasures? Or even better, supporting local residents to get together to make the invisible visible.

For most, this act of discovery is very powerful and revelatory. But discovery alone changes very little. Having a list of assets should not be thought of as an action step. A further and deeper inquiry is needed to understand how the various assets that have been discovered can be connected more productively. Deepening the connection between individual capacities, the power of associations, the resources of institutions, the potential of the built and natural environment, the potential of the local economy and, the abundant richness of local cultures is not a once off data gathering exercise. It is an on-going relationship building process.

This is beyond the capacity of a Google search, a professional intervention, or even a lone citizen. Making the invisible visible is an invitation to create interdependence by inviting citizens to act their way into interdependence from the get go, by starting a new conversation which in turn leads to new discoveries and connections. It takes many citizens, in deep and meaningful connection with each other, to uncover the hidden capacity and potential that is in every community, waiting to be discovered, like a sundial in the shade.

In the late 1980s Professors John McKnight and Jody Kretzmann travelled across 300 neighbourhoods in 20 cities in North America, learning of stories of citizen-led change. What they discovered were six identifiable building blocks that are used by local residents to build community from inside out (what they later came to call assets). While knowing these building blocks in principle will not enable us to discover the undiscovered assets in our own neighbourhoods, they do provide a helpful frame of reference. The six building blocks are described as follows:

1# The skills, gifts and passions of local residents.

2# The power of local social networks/associations.

3# The resources of public, private and non-profit institutions.

4# The physical resources of a local place.

5# The economic resources of a local place.

6# The stories of our shared lives.

There is no doubting that the intentional acts of discovery and connection across an entire neighbourhood (small bounded place) is a time consuming one. However, if we are committed to sustainable community development, then the slower messier route, such as this, is essential. Making the invisible visible is a starting point, but it is not yet an action step per se, it’s a foundational step and it is where a community deepens its appreciation of what capacities it has, ensuring any support from the outside is relevant to the local context. Without taking the time to build this interconnectedness and trust across a place, the following can occur (often instigated by well-intentioned outside agencies):

• Displacement of local invention – whereby projects and initiatives, with resources and expertise (and good intention) replicate what it is that local people are already doing for themselves indigenously, thereby disabling and eclipsing local capacity.

• Stifling of local invention – when the working assumption in a given community is that the only way things will get better is when someone from outside comes in to make them better, or that a community can only act when it has permission from outside, it serves to dampen down enthusiasm and creativity. In the same way professionalisation or credentialising of community functions results in a major attrition in citizen-led action. As professionalisation increases, citizenship retreats.

In conclusion, it is important to state that making the invisible visible is not a positive psychology technique or indeed a technique in any sense; it is an intentional citizen-led act of building power and collective efficacy. Citizens build power as they form mutual trust and connection through action. In so doing, they come to recognise much (though not all) of what they need to make change is close at hand. This is not to suggest that a community has everything it needs internally, but instead to affirm it can’t know what it needs externally until it discovers what it has internally, and that what it has locally is of far greater value than most recognise. Once a community understands what it has within, and in turn what it requires from the outside, they come to confidently occupy a powerful political space from where they can begin to leverage significant change for the future.

So, if you are an outside agency seeking to help and you must stick with your organisation theme or mission, for example, if you are interested in health, ask local residents: “what is it you do to be healthy in this place, and how can we support you?”

If you’re interested in safety, ask local residents: “how do you create safety in this place, and how can we support your efforts? This reframe creates two shifts. Firstly, a shift from a more traditional transactional relationship of service provider/client, to one of facilitator/citizen. Secondly, this creates a shift from a single issue focus/theme or a silo-ed approach which involves only working with target populations to a more holistic place-based approach.

Having said that, it’s worth remembering that most of the things people do to be healthy or safe are done by people who are not thinking that what they are doing is healthy or safe. So the more you can set your agency agendas to one side and simply get to know what the community cares about, the more likely you are to build community while also addressing your organisation’s concerns.

Hence, why we suggest instead of being helpful; be curious: after all your agency map is never the territory.

Additional reading/resources

7 Top Tips for supporting citizen driven community building series