Abstract

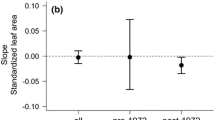

The frequency of extreme warm years is increasing across the majority of the planet. Shifts in plant phenology in response to extreme years can influence plant survival, productivity, and synchrony with pollinators/herbivores. Despite extensive work on plant phenological responses to climate change, little is known about responses to extreme warm years, particularly at the intraspecific level. Here we investigate 43 populations of white ash trees (Fraxinus americana) from throughout the species range that were all grown in a common garden. We compared the timing of leaf emergence during the warmest year in U.S. history (2012) with relatively non-extreme years. We show that (a) leaf emergence among white ash populations was accelerated by 21 days on average during the extreme warm year of 2012 relative to non-extreme years; (b) rank order for the timing of leaf emergence was maintained among populations across extreme and non-extreme years, with southern populations emerging earlier than northern populations; (c) greater amounts of warming units accumulated prior to leaf emergence during the extreme warm year relative to non-extreme years, and this constrained the potential for even earlier leaf emergence by an average of 9 days among populations; and (d) the extreme warm year reduced the reliability of a relevant phenological model for white ash by producing a consistent bias toward earlier predicted leaf emergence relative to observations. These results demonstrate a critical need to better understand how extreme warm years will impact tree phenology, particularly at the intraspecific level.

Adapted from (Marchin et al. 2008) and USDA Forest Service (www.na.fs.fed.us)

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Anderson JL, Richardson EA (1986) Validation of winter chill unit and flower bud phenology models for ‘monmorency’ sour cherry. Acta Hortic 184:71–77

Augspurger CK (2013) Reconstructing patterns of temperature, phenology, and frost damage over 124 years: spring damage risk is increasing. Ecology 94:41–50

Basler D, Körner C (2012) Photoperiod sensitivity of bud burst in 14 temperate forest tree species. Agric For Meteorol 165:73–81

Borchert R, Robertson K, Schwartz MD, Williams-Linera G (2005) Phenology of temperate trees in tropical climates. Int J Biometerol 50:57–65

Burnham KP, Anderson DR (2002) Model selection and multimodel inference: a practical information-theoretic approach. Springer-Verlag, New York, NY, USA

Cesaraccio C, Spano D, Snyder RL, Duce P (2004) Chilling and forcing model to predict bud-burst of crop and forest species. Agric For Meteorol 126:1–13. doi:10.1016/j.agrformet.2004.03.002

Chang CT, Wang HC, Huang CY (2013) Impacts of vegetation onset time on the net primary productivity in a mountainous island in Pacific Asia. Environ Res Lett 8:11. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/8/4/045030

Chang H, Castro CL, Carillo CM (2015) The more extreme nature of U.S. warm season climate in the observational record and two “well-performing” dynamically downscaled CMIP3 models. J Geophys Res 120:8244–8263

Chuine I, Cour P, Rousseau DD (1998) Fitting models predicting dates of flowering of temperate-zone trees using simulated annealing. Plant Cell Environ 21:455–466. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3040.1998.00299.x

Chuine I, Kramer K, Hanninen H (2003) Plant development models. In: Schwartz M (ed) Phenology: an integrative environmental science. Springer, Rotterdam, pp 217–235

Clark JS, Salk C, Melillo J, Mohan J, Anten N (2014) Tree phenology responses to winter chilling, spring warming, at north and south range limits. Funct Ecol 28:1344–1355. doi:10.1111/1365-2435.12309

Cleland EE, Allen JM, Crimmins TM, Dunne JA, Pau S, Travers SE, Zavaleta ES, Wolkovich EM (2012) Phenological tracking enables positive species responses to climate change. Ecology 93:1765–1771

Cook BI, Wolkovich EM, Parmesan C (2012) Divergent response to spring and winter warming drive community level flowering trends. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109:9000–9005. doi:10.1073/pnas.1118364109

Cooke JE, Eriksson ME, Junttila O (2012) The dynamic nature of bud dormancy in trees: environmental control and molecular mechanisms. Plant Cell Environ 10:1707–1728

Dantec CF, Vitasse Y, Bonhomme M, Louvet JM, Kremer A, Delzon S (2014) Chilling and heat requirements for leaf unfolding in European beech and sessile oak populations at the southern limit of their distribution range. Int J Biometereol 58:1853–1864. doi:10.1007/s00484-014-0787-7

Donat MG, Alexander LV, Yang H, Durre I, Vose R, Dunn RJH, Willett KM, Aguilar E, Brunet M, Caesar J, Hewitson B, Jack C, Klein Tank AMG, Kruger AC, Marengo J, Peterson TC, Renom M, Oria Rojas C, Rusticucci M, Salinger J, Elrayah AS, Sekele SS, Srivastava AK, Trewin B, Villarroel C, Vincent LA, Zhai P, Zhang X, Kitching S (2013) Updated analyses of temperature and precipitation extreme indices since the beginning of the twentieth century: the HadEX2 dataset. J Geophys Res Atmos 118:2098–2118. doi:10.1002/jgrd.50150

Ellwood ER, Temple SA, Primack RB, Bradley NL, Davis CC (2013) Record-breaking early flowering in the Eastern United States. PLoS One 8:9. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0053788

Fahey RT (2016) Variation in responsiveness of woody plant leaf out phenology to anomalous spring onset. Ecosphere. doi:10.1002/ecs2.1209

Forrest JRK (2015) Plant-pollinator interactions and phenological change: what can we learn about climate impacts from experiments and observations? Oikos 124:4–13. doi:10.1111/oik.01386

Friedl MA, Gray JM, Melaas EK, Richardson AD, Hufkens K, Keenan TF, Bailey A, O’Keefe J (2014) A tale of two springs: using recent climate anomalies to characterize the sensitivity of temperate forest phenology to climate change. Environ Res Lett 9:9. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/9/5/054006

Fu YH, Campioli M, Deckmyn G, Janssens IA (2013) Sensitivity of leaf unfolding to experimental warming in three temperate tree species. Agric For Meteorol 181:125–132. doi:10.1016/j.agrformet.2013.07.016

Hansen J, Sato M, Ruedy R (2012) Perception of climate change. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109:E2415–E2423. doi:10.1073/pnas.1205276109

Hunter AF, Lechowicz MJ (1992) Predicting the timing of budburst in temperate trees. J Appl Ecol 29:597–604

IPCC (2012) Managing the risks of extreme events and disaster to advance climate change adaptation. A special report of working groups I and II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

IPCC (2013) Climate change 2013: the physical science basis. Contribution of working group I to the fifth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, United Kingdom New York, NY, USA

Jeong S-J, Ho C-H, Gim H-J, Brown ME (2011) Phenology shifts at start vs. end of growing season in temperate vegetation over the Northern Hemisphere for the period 1982–2008. Glob Chang Biol 17:2385–2399. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02397.x

Jeong S-J, Medvigy D, Shevliakova E, Malyshev S (2012) Uncertainties in terrestrial carbon budgets related to spring phenology. J Geophys Res. doi:10.1029/2011JG001868

Laube J, Sparks TH, Estrella N, Hofler J, Ankerst DP, Menzel A (2014) Chilling outweighs photoperiod in preventing precocious spring development. Glob Chang Biol 20:170–182. doi:10.1111/gcb.12360

Liang L (2015) Geographic variations in spring and autumn phenology of white ash in a common garden. Phys Geogr. doi:10.1080/02723646.2015.1123538

Luedeling E, Brown PH (2011) A global analysis of the comparability of winter chill models for fruit and nut trees. Int J Biometeorol 55:411–421. doi:10.1007/s00484-010-0352-y

Luedeling E, Zhang MH, McGranahan G, Leslie C (2009) Validation of winter chill models using historic records of walnut phenology. Agric For Meteorol 149:1854–1864. doi:10.1016/j.agrformet.2009.06.013

Luterbacher J, Liniger MA, Menzel A, Estrella N, Della-Marta PM, Pfister C, Rutishauser T, Xoplaki E (2007) Exceptional European warmth of autumn 2006 and winter 2007: Historical context, the underlying dynamics, and its phenological impacts. Geophys Res Lett 34:6. doi:10.1029/2007gl029951

Marchin RM, Sage EL, Ward JK (2008) Population-level variation of Fraxinus americana (white ash) is influenced by precipitation differences across the native range. Tree Physiol 28:151–159

Marchin RM, Salk CF, Hoffmann WA, Dunn RD (2015) Temperature alone does not explain phenological variation of diverse temperate plants under experimental warming. Glob Chang Biol 21:3138–3151

Migliavacca M, Sonnentag O, Keenan TF, Cescatti A, O’Keefe J, Richardson AD (2012) On the uncertainty of phenological response to climate change, and implications for a terrestrial biosphere model. Biogeosciences 9:2063–2083

Morin X, Lechowicz MJ, Augspurger C, O’Keefe J, Viner D, Chuine I (2009) Leaf phenology in 22 North American tree species during the 21st century. Glob Chang Biol 15:961–975. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2008.01735.x

Mutiibwa D, Vavrus S, McAfee S, Albright T (2015) Recent spatiotemporal patterns in temperature extremes across conterminous United States. J Geophys Res Atmos 120:7378–7392

National Weather Service (2014) Monthly and seasonal mean temperature for Topeka, KS

NOAA (2012) State of the climate: national overview for annual 2012

Pletsers A, Caffarra A, Kelleher C, Donnelly A (2015) Chilling temperature and photoperiod influence the timing of bud burst in juvenile Betula pubescens Ehrh. and Populus tremula L. trees. Ann For Sci 72:941–953

Poland TM, McCullough DG (2006) Emerald ash borer: invasion of the urban forest and the threat to North America’s ash resource. J For 104:118–124

Polgar CA, Primack RB (2011) Leaf-out phenology of temperate woody plants: from trees to ecosystems. New Phytol 191:926–941. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03803.x

Polgar CA, Gallinat A, Primack RB (2013) Drivers of leaf-out phenology and their implications for species invasions: insights from Thoreau’s Concord. New Phytol 202:106–115

Press WH, Teulosky SA, Vetterling WT, Flannery BP (1992) Numerical recipes in C: the art of scientific computing, 2nd edn. Cambridge University Press, New York

Primack RB, Laube J, Gallinat A, Menzel A (2015) From observations to experiments in phenology: investigating climate change impacts on trees and shrubs using dormant twigs. Ann Bot 116:889–897

Rea R, Eccel E (2006) Phenological models for blooming of apple in a mountainous region. Int J Biometeorol 51:1–16. doi:10.1007/s00484-006-0043-x

Richardson EA, Seeley SD, Walker DR (1974) A model for estimating the completion of rest for ‘Redhaven’ and ‘Elberta’ peach trees. HortSci 9:331–332

Rousi M, Pusenius J (2005) Variations in phenology and growth of European white birch (Betula pendula) clones. Tree Physiol 25:201–210

Rutishauser T, Luterbacher J, Defila C, Frank D, Wanner H (2008) Swiss spring plant phenology 2007: Extremes, a multi-century perspective, and changes in temperature sensitivity. Geophys Res Lett 35:5. doi:10.1029/2007gl032545

Salk CF (2011) Will the timing of temperate deciduous trees’ budburst and leaf senescence keep up with a warming climate? PhD dissertation, Department of Biology, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, USA

Sanz-Pérez V, Castro-Díez P, Valladares F (2009) Differential and interactive effects of temperature and photoperiod on budburst and carbon reserves in two co-occurring Mediterranean oaks. Plant Biol 11:142–151. doi:10.1111/j.1438-8677.2008.00119.x

Suzuki M, Yoda K, Suzuki H (1996) Phenological comparison of the onset of vessel formation between ring-porous and diffuse-porous deciduous trees in a Japanese temperate forest. IAWA J 17:431–444

United States Weather Bureau (1942) Kansas weather and climate. Kansas State Printing Plant, W.C. Austin, State Printer, Topeka

Vihera-Aarnio A, Sutinen S, Partanen J, Hakkinen R (2014) Internal development of vegetative buds of Norway spruce trees in relation to accumulated chilling and forcing temperatures. Tree Physiol 34:547–556. doi:10.1093/treephys/tpu038

Vitasse Y, François C, Delpierre N, Dufrêne E, Kremer A, Chuine I, Delzon S (2011) Assessing the effects of climate change on the phenology of European temperate trees. Agric For Meteorol 151:969–980. doi:10.1016/j.agrformet.2011.03.003

Vitasse Y, Lenz A, Kollas C, Randin CF, Hoch G, Körner C (2014a) Genetic vs. non-genetic responses of leaf morphology and growth to elevation in temperate tree species. Funct Ecol 28:243–252. doi:10.1111/1365-2435.12161

Vitasse Y, Lenz A, Korner C (2014b) The interaction between freezing tolerance and phenology in temperate deciduous trees. Front Plant Sci 5:541. doi:10.3389/fpls.2014.00541

Wang J, Ives NE, Lechowicz MJ (1992) The relation of foliar phenology to xylem embolism in trees. Funct Ecol 6:469–475. doi:10.2307/2389285

Way DA, Montgomery RA (2014) Photoperiod constraints on tree phenology, performance and migration in a warming world. Plant Cell Environ 38(9):1725–1736. doi:10.1111/pce.12431

Weaver SJ, Kumar A, Chen MY (2014) Recent increases in extreme temperature occurrence over land. Geophys Res Lett 41:4669–4675. doi:10.1002/2014gl060300

Yordanov YS, Ma C, Strauss SH, Busov VB (2014) EARLY BUD-BREAK 1 (EBB1) is a regulator of release from seasonal dormancy in poplar trees. Proc Natl Acad of Sci USA 111:10001–10006. doi:10.1073/pnas.1405621111

Yu H, Luedeling E, Xu J (2010) Winter and spring warming result in delayed spring phenology on the Tibetan Plateau. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:22151–22156. doi:10.1073/pnas.1012490107

Zohner C, Renner S (2014) Common garden comparison of the leaf-out phenology of woody species from different native climates, combined with herbarium records, forecasts long-term change. Ecol Lett 17:1016–1025

Acknowledgements

We thank K. Becklin, J. Medeiros, K. Kluthe, E. Duffy, S. M. Walker II, T. Leibbrandt, and C. Bone for field assistance, as well as E. Luedeling, S.-J. Jeong, A. Richardson, M. Migliavacca, and M. T. Holder for helpful modeling advice. We thank the University of Kansas Field Station staff for maintaining the common garden. This work was supported by NSF CAREER and other IOS awards to JKW. An NSF C-CHANGE IGERT fellowship supported JMC. MEO and JKW also acknowledge University of Kansas GRF grants. The Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and the University of Kansas Research Investment Council also provided funding.

Author contribution statement

JMC, MEO, RMM and JKW conceived and designed the experiments. JMC, LMG, JHS, RMM and JKW conducted field work, and MEO, JMC and JKW developed and performed modeling and statistical analyses. JMC, MEO, JN and JKW wrote the manuscript; all authors provided editorial advice.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Tim Seastedt.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Carter, J.M., Orive, M.E., Gerhart, L.M. et al. Warmest extreme year in U.S. history alters thermal requirements for tree phenology. Oecologia 183, 1197–1210 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-017-3838-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-017-3838-z