How Republicans Might 'Repair' Obamacare Before Repealing It

Most GOP lawmakers want to demolish the health law right away. Senator Lamar Alexander wants to rescue it first.

Lamar Alexander’s preferred metaphor for the current state of the Affordable Care Act is that of a collapsing bridge. Rising premiums and fewer coverage options in many states have destabilized the law’s insurance exchanges, the veteran Republican senator argues, and Congress must step in to rescue consumers trapped in a system of dwindling and increasingly expensive health-care plans.

Most Republicans in Washington share this view, but they and Alexander differ on what to do about the bridge. Ardent conservatives and their allies in the party leadership want to level the thing right away and build a new overpass immediately—or as quickly as legislatively possible in the slow-motion ways of Congress. That’s the “repeal-and-replace” mantra that Republicans have sounded on Obamacare for nearly seven years, right up through the election of President Trump.

Alexander, however, is talking up a different approach. He wants first to repair the law—to prop it up for as long as two or three years—to protect Americans who currently rely on its provisions while lawmakers figure out how to replace it. “What do you do about a collapsing bridge? You don’t go to the edge of the bridge and argue about whose fault it was that it’s in disrepair,” he said last week near the end of a Senate hearing he convened. “You send in a rescue team and you go to work to repair it so that nobody else is hurt by it. And you start to build a new bridge, and only when that new bridge is complete and people can drive safely across it, you close the old bridge.”

In the often confusing semantics of the Republican debate over health care, that translates to: Repair the law first, then devise a replacement, and only once those two events happen would the final repeal of the Affordable Care Act take effect. And for advocating that kind of lengthy, complicated demolition, one of the GOP’s senior-most health-care policymakers finds himself on an island nearly unto himself.

Alexander is chairman of the Senate’s Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee—known colloquially on Capitol Hill as the HELP Committee. The panel is one of two in the Senate charged with writing the legislation that will repeal, repair, or otherwise alter Obamacare. Alexander, a 76-year-old Tennessean serving in his third term, has been around the top ranks of the Republican Party for the last four decades; on his resumé are two terms as governor of Tennessee in the 1980s, a stint as education secretary under President George H. W. Bush, and a pair of failed bids for president in 1996 and 2000. Until a few years ago, he served in the Republican leadership in the Senate. When he quit in 2012, he cited the constraints of the partisan post and a desire to be liberated to “spend more time working for results on the issues I care most about” as reasons for resigning.

That decision paid off for Alexander in 2015, when he collaborated with Democratic Senator Patty Murray of Washington state to rewrite the George W. Bush-era No Child Left Behind education law, one of the few bipartisan accords in the final years of the Obama administration. And it seems to be informing his willingness to veer away from the party line on immediately ripping up the health law.

He’s actually been advocating his go-slow approach on Obamacare since the first days after the election, when jubilant conservatives were talking about repealing it so quickly that Trump would be able to sign the legislation as soon as he stepped into the Oval Office. Yet with each passing day, more Republicans seem to be inching closer to Alexander’s position. Supporters of the ACA have flooded into town-hall meetings that GOP lawmakers have held in their districts, replicating the Tea Party strategy of 2009 that nearly blew up the law before its enactment in 2010. In leaked audio of a private party meeting in Philadelphia last month, rank-and-file Republicans raised concerns about the political consequences of a hasty repeal. Last week, Bloomberg noted that lawmakers besides Alexander shifted their message from promoting repeal to using the word “repair” in connection with the Affordable Care Act. (They didn’t get there by accident: Polls show there is much broader support for fixing the law than for repealing it entirely.)

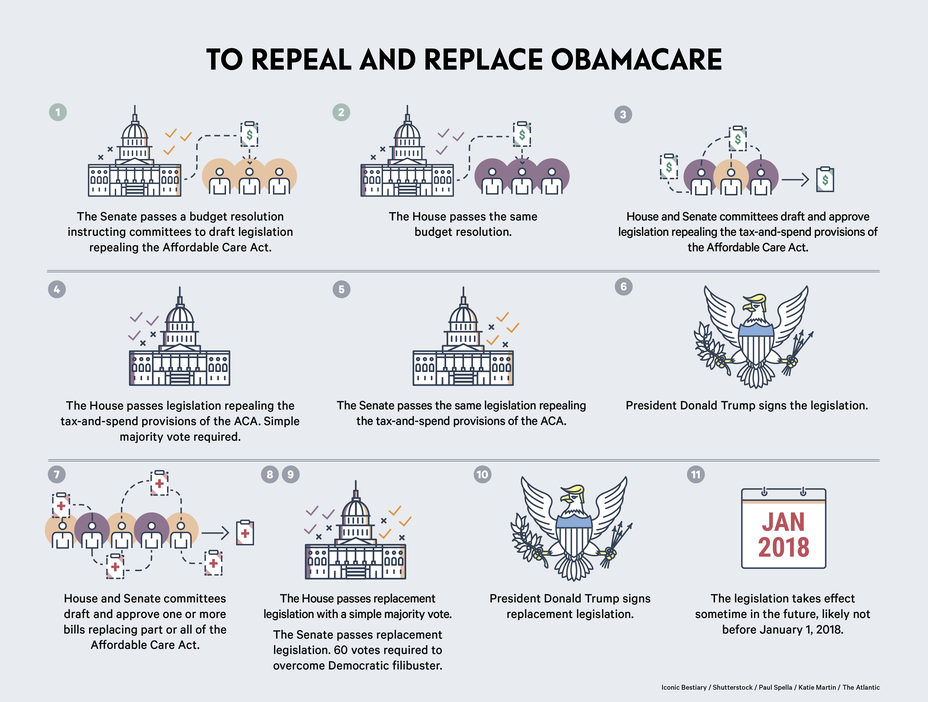

And on Sunday, Trump himself seemed to push back his timeline for action on health care, telling Bill O’Reilly in an interview before the Super Bowl that his administration’s plan for fixing the system might not be ready until 2018. The president had previously vowed to deliver a proposal to Congress shortly after his yet-to-be-confirmed health secretary, Tom Price, took office. While the House and Senate have taken the first steps toward fast-tracking repeal, actual legislation is not close to coming up for a vote.

Amid the division among Republicans, Alexander has, ever so gingerly, stepped into the void. He’s given no details about his legislative proposal, and he declined an interview for this story. But the senator’s remarks in speeches and in hearings, and conservations with congressional aides and outside health-policy experts, offer some ideas about what he might be considering.

Alexander wants to focus first on stabilizing the individual insurance market, which accounts for about 6 percent of the country’s insured population, before tackling other thorny questions like the ACA’s expansion of Medicaid. And unlike the repeal of the law, this bill would have to be bipartisan and gain 60 votes in the Senate, he said in the hearing he convened last week. The urgency, as Alexander sees it, is that insurers must decide whether they are going to participate in the Obamacare exchanges in 2018, and how they will price their plans, by this spring. “It can be done temporarily,” he said of his repair bill. “It can be done in effect to stabilize that market for two or three years while we discuss everything else. And I think that it means that Republicans are going to have to approve some things we normally might not support, and Democrats will have to do some things they normally might not do during this transition.”

What might be those uncomfortable policies that Republicans would have to approve? Essentially, they’d have to appropriate money to subsidize insurance companies to keep them from exiting the market. They could renew a reinsurance program that expired at the end of 2016 that helped insurers offset the cost of insuring older, less healthy customers. And lawmakers could approve the continuation of subsidies to lower deductibles and co-pays for lower-income Americans. “Money greases a lot of wheels,” said Larry Levitt, senior vice president at the Kaiser Family Foundation. The reinsurance program, he said, “would essentially provide an infusion of cash to insurers to help pay the cost for people with expensive illnesses. That would help bring premiums down and help provide greater stability to the market.”

The problem politically is that many Republicans have long decried the program as an insurer bailout. “They might have to re-label it,” Levitt joked. (With a push from Senator Marco Rubio of Florida, the GOP succeeded in getting rid of another source of financial relief for insurance companies known as risk corridors in 2014.)

As for the continuation of subsidies, the GOP-controlled House actually sued the Obama administration over the money in 2015, arguing that the government was dispensing tax credits without explicit approval from Congress, which constitutionally holds the power of the purse. A federal judge initially ruled in the House’s favor, and the Trump administration hasn’t said whether it will pick up the Obama administration’s defense of the subsidies. Alexander is now floating the idea of authorizing them anyway as a way of keeping the exchanges afloat for another couple years.

At last week’s hearing, the insurance industry’s top lobbyist, Marilynn Tavenner of America’s Health Insurance Plans, urged senators to approve both the reinsurance program and the subsidies. She also pushed for tightening eligibility and payment requirements for enrolling in the exchanges, which are changes that Price might be able to make unilaterally if and when he becomes health and human services secretary. But Price could also choose to take immediate steps that insurers believe would destabilize the market, such as declining to enforce the mandate that individuals buy coverage or pay a tax penalty. That authority follows from the executive order Trump signed when he took office directing federal agencies to ease the “burden” of Obamacare on consumers and businesses.

Alexander’s far bigger challenge will be persuading enough senators in both parties to go along with him on a short-term fix for the ACA—not to mention members of the more polarized House of Representatives. He and other Republicans have pointed out to Democrats that even if Hillary Clinton had won the election, the insurance exchanges would have needed congressional action to ensure their long-term viability. And the policies that he is now weighing are some of the same ones that, experts acknowledge, a Clinton administration likely would have pressed for as well.

Democrats, however, are demanding that Republicans take repeal off the table before they negotiate on any changes—a concession that Alexander can’t, and won’t, offer. “We all agree that improvements can be made, and do it in a bipartisan way,” said Murray, the top Democrat on the HELP Committee. Then she adopted her own version of Alexander’s “bridge” metaphor. “Those are good discussions, but we can’t repair the roof while the president and Republicans are burning the house down.”

Bringing conservatives along will be equally difficult. Hardline advocacy groups like Heritage Action and FreedomWorks have criticized legislative proposals that fall short of the bill Republicans passed in 2015 that repeals most of the law (and was vetoed by then-President Obama). And GOP leaders like House Speaker Paul Ryan moved quickly over the weekend to tamp down suggestions that the party was backing away from its long-standing pledge. On Sunday night, Alexander posted a new statement on Medium that sought to square his own push for “repair” with the leadership’s goal of repeal and replace. “While Congress will vote to repeal and replace Obamacare this year,” he wrote, “the repeal of Obamacare finally will become effective when our reforms are implemented and we have concrete, practical alternatives. I believe this is what the president means when he says we will repeal and replace Obamacare simultaneously and what Speaker Ryan means when he says we will repeal and replace Obamacare concurrently.”

Advocates of saving the Affordable Care Act gave Alexander credit for an admirable, if lonely, push for bipartisanship. “Senator Alexander is not an ideologue and he’s generally a practical legislator,” said Ron Pollack, executive director of health-care consumer-advocacy group Families USA. But like many others in Washington, he was deeply skeptical he would succeed. “Whether his caucus and the House caucus enable him to do that,” Pollack said, “is hard to say.”