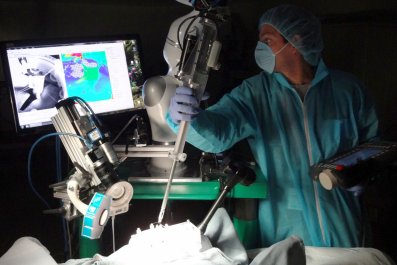

Will Strahl walked up to my door with a massive black briefcase in his hand, the kind you could use to tote a dirty bomb. Once inside my living room, he cracked open the case and removed a laptop, a small amplifier, a resealable plastic bag of stainless steel–tipped electrodes and a jar of conductive gel. He applied the gel to the peak of my forehead, then attached electrodes to my skull and ground wires to my ears. I was about to play a video game with my brain.

To succeed, I needed only to keep the car moving, the music playing and a gray fog from enshrouding the entire screen. To pull off those feats, I had to keep my mind as calm and focused as possible. If I closed my eyes or clenched my jaw or shifted in my seat, the car stalled or the screen went gray or the music faded to a whisper. There were other cars in the race, but the true objective wasn't to beat them. It was to rebalance my brain.

Strahl is a doctoral student in psychology at Pacific University in Portland, Oregon, but before that he worked for a neurologist in Los Angeles who founded a company called the Peak Brain Institute, which has ventured into neurofeedback, a decades-old field of neuroscience that word-of-mouth and some new technology have made newly popular. The promise of neurofeedback is to shift our brain waves back to health without drugs, exercise or even meditation. Clients suffering from attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, anger or depression can simply sit in a comfortable chair for half-hour sessions with a few wires protruding from their scalp and get a mental tune-up, if not a complete rewiring of an off-kilter brain.

It sounds like quackery, but it isn't. Neurofeedback, which uses real-time displays of brain activity to teach the brain to self-regulate, is a technique neurologists have wielded since the 1960s. Back then, NASA was concerned about astronauts having rocket fuel–induced seizures. They approached Barry Sterman, a researcher at the University of California, Los Angeles, School of Medicine, for help. Sterman soon discovered that he could minimize the damaging effects of rocket fuel on cats with an early form of neurofeedback he developed.

The way neurofeedback works is fairly simple: Electrodes are attached to various parts of the skull and hooked up to a computer or tablet of some kind with installed software that reads activity in those regions and computes an appropriate response delivered back to the brain. The brain then uses that data to adjust itself, in the same way that you might be inspired to fix an-out-of place lock of hair while looking in the mirror. As the brain changes, the feedback changes. "Think of neurofeedback as a kind of learning for the brain," says Kirk Little, a Cincinnati psychologist and president of the International Society for Neurofeedback and Research. "If you tell a dog to sit, push its butt down and give it a cookie 100 times, the dog is going to learn how to sit on its own [when] you just shake the [cookie] box. You're doing the same thing with the brain's electrical discharges—rewarding people for modifying their brain waves."

While the practice grew slowly in the decades after Sterman's initial work, recent advances in technology and processor speeds have allowed more practitioners to offer the services with less of an investment, and a consensus has arisen based on research that peaked in the early aughts that the brain is in fact neuroplastic. Neurofeedback has shown demonstrable results in hundreds of patients over the past few decades, Little says, with more than 500 peer-reviewed research articles published on the topic in the past few years alone. Robert Longo, a Lexington, North Carolina, counselor on the board of directors for the International Society for Neurofeedback and Research, says it's now widely accepted that the notion of rewiring the brain isn't hocus-pocus. "The idea of neuroplasticity is really starting to catch on in the wired public and scientific communities. It's very clear now that it works," says Little.

I first stumbled across the concept of neurofeedback while researching a story on anger in 2014. A couple of the experts I interviewed mentioned the practice, and I found a company called Brain State Technologies that offered a neurofeedback treatment it called Brainwave Optimization. The company connected me with a practitioner in New York City, and in April that year I underwent two sessions. After the first session, I felt as if I'd just finished meditating, and the world seemed a little brighter. After the second, I felt like I'd taken a Xanax.

More committed users sometimes—though not always—see even more dramatic and long-lasting effects. Longo's wife, for example, started using neurofeedback after she fell down a flight of stairs and suffered a series of headaches and vertigo. After 30 sessions, "it made a 100 percent difference," she says. "This is one of mental health's best-kept secrets," Longo adds. "The pharmaceutical companies don't like us because it gets people off of drugs. But there's a growing amount of literature and research, and in the next five or 10 years you're going to see a lot of support when we say we can treat things like traumatic brain injuries, anxiety, depression, ADHD, insomnia, migraine headaches and people who have had strokes."

Charles Tegeler, a neurology professor at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center in North Carolina, got into the field after running a stroke center for 15 years. He became increasingly concerned that stress was killing people, he says, and "putting people on drugs was just a big Band-Aid." In 2009, Tegeler heard about Brain State. "I thought it sounded like bunk," he says. But his daughter had developed migraine headaches so excruciating she'd missed most of her classes during the previous semester. Tegeler decided she could undergo the company's brain wave optimization. "If it helps her headaches, we'll talk," he says of his feelings before the sessions. Tegeler also tried it himself, to see if it could do anything for his irregular heartbeat. After 10 sessions in five days, Tegeler's heart was back to normal, and his daughter's headaches were gone.

In 2009, he founded a research institute at Wake Forest called HIRREM, which stands for "high-resolution, relational, resonance-based, electroencephalic mirroring." The facility has enrolled 400 people in five neurofeedback research projects, all using Brain State's technology. Participants included people with traumatic brain injuries, insomniacs and people suffering from depression or stress. Most of HIRREM's participants have seen improvement, Tegeler says. On balance, the results are "like condensing three years of medication into three days," with only a small rate of adverse effects. The center is about to release the findings of a placebo-controlled study of 104 people with insomnia and is launching trials later this year to see if neurofeedback helps those who suffer from PTSD.

Not everyone responds that well to neurofeedback. Search the web, and there are blog posts from clients who've undergone neurofeedback sessions and complain that they resulted in bouts of insomnia or anxiety. "You can train people in the wrong way," Little says. "You can put sensors in the wrong spots, the training frequencies in the wrong direction. You can make a person an insomniac, make people more angry and agitated."

Nevertheless, the number of patients using Brain State's technology—mostly in offices set up by a network of practitioners across the globe—has surged from 25,000 five years ago to 100,000 today, founder Lee Gerdes says. Last fall, Gerdes gambled that he'd find demand for a take-home version of his product. He launched a Kickstarter campaign for the Braintellect 2, a portable headband that offers a less-involved version of the procedure I underwent in New York. He raised $95,000 in two months and started shipping the individual units not long after the new year.

The headband straps to the back of the skull and rests on the nose, sort of like Geordi La Forge's glasses in Star Trek . It is equipped with sensors that deliver activity readings from the brain to a Bluetooth-enabled device that communicates with an included media tablet. The tablet stores software that receives the brain activity information and uses it to output a series of sounds—tones and chimes—that change constantly, depending on the input.

I was one of the first people to receive the Braintellect, and Gerdes warned me there would be "kinks" to work out. In the first few short sessions I tried, I had trouble getting the headset to fit comfortably and securely, so Gerdes sent me a new set of sensors and ultimately a whole new and more flexible unit. Still, I'm a little spooked to try it. Strahl's "video game" seemed to push me in the right neuro-direction. The more I calmed myself and focused on moving the car through a swamp, the more consistently the car moved. When it stalled—and it stalled frequently—I was frustrated and mentally flailing to try to get it going again, which was counterproductive. After two sessions held over two days, I got a little better at the game and felt a bit more clear-headed afterward. But self-administering is a different beast, and not everyone thinks neurofeedback is ready—or will ever be ready—for at-home application.

Not long after venturing into the neurofeedback field in 2005, Little found out the hard way that self-experimentation—even with expert training—can easily take a wrong turn. "My wife would say, 'What's the matter with you?' And I'd say, 'Nothing is the matter with me!' And she'd say, 'That attitude, right there.' I had the beta waves trained too high, which made me irritable and obsessive," he recalls. Little tells me he'd never "publicly" advise someone to perform neurofeedback on themselves, but "if you're an adult who wants to do this, it's your prerogative," he says. "It could be really great for you, or it could really mess you up."