Sir Terry Pratchett’s unfinished autobiography reveals his descent into the “haze of Alzheimer’s” and the moment the esteemed novelist realised he was “dead”, according to a new docudrama.

Terry Pratchett: Back in Black, to be broadcast on BBC2 on 11 February, draws on the author’s notes for the incomplete autobiography, which was his last work before his death in March 2015 aged 66.

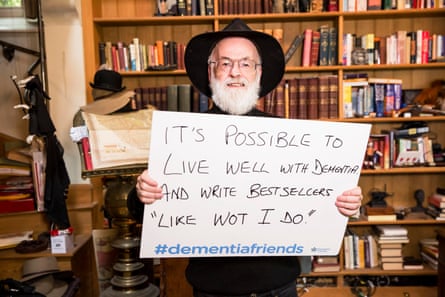

Pratchett was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in December 2007, and the notes provide an insight into the anger he felt over his debilitating condition.

The programme includes footage of the frail-looking author shortly before his death, and features an appearance from Rob Wilkins, Pratchett’s long-term assistant and collaborator on the autobiography, the Times reports(£).

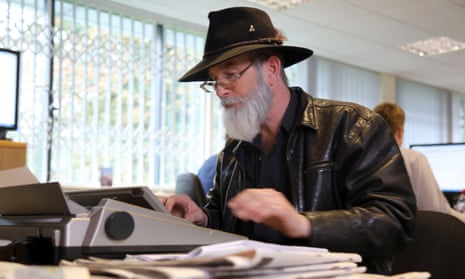

In the programme, Wilkins recalls the day in autumn 2007 when he and Pratchett realised something strange had happened. He says Pratchett came into his office saying: “The ‘S’ on my keyboard has gone … Come on, what have you done with it?”

It was in late 2014 that Pratchett realised he was not the same writer he used to be. “We had a good day working on the biography and he said to me: ‘Rob, Terry Pratchett is dead.’ Completely out of the blue. I said: ‘Terry look at the words you have written today. It is fantastic.’ And he said: ‘No, no. Terry Pratchett is dead.’”

Wilkins said that towards the end of his life Pratchett became increasingly angered by his disease. “He could see how it was affecting him, how it was tripping him up and I knew we were up against it for time. We had to get the words down and with that white heat, with that white anger driving him to write seven whole novels through the haze of Alzheimer’s.”

After a career in journalism, Pratchett began writing full-time in 1987. He is the author of more than 70 fantasy novels translated into 37 languages. His series of Discworld novels sold more than 70m copies and made him one of the country’s most successful writers.

Before being knighted in 2009 and accruing a net worth of about $65m, Pratchett had a “humble childhood”, according to the notes for his final work.

He was the son of a mechanic and a secretary, and got a job in his local library after being inspired by The Wind in the Willows – a time, he wrote, when he “was probably at my happiest”.

He was bullied at school because “I had a mouthful of speech impediments that left me with a voice that sounded like David Bellamy with his hand caught inside an electric fire. But it was not the kids that really got to me, it was the crushing of my boyhood dreams by someone 3ft taller.”

The headmaster of Holtspur School in Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire, took a “rather vicious dislike to me” and thought “he could tell how successful you were going to be in later life by how well you could read or write at the age of six”, he added.

On his Alzheimer’s, Pratchett wrote: “On the first day of my journalistic career I saw my first corpse – some unfortunate chap fell down a hole in a farm and drowned in pig shit. All I can say is that, compared with his horrific demise, Alzheimer’s is a walk in the park. Except with Alzheimer’s my park keeps changing.

“The trees get up and walk over there, the benches go missing and the paths seem to be unwinding into particularly vindictive serpents.“I always dreamt that when I died I would be sat in a deckchair with a glass of brandy listening to Thomas Tallis on the iPod. But I had Alzheimer’s, so I forgot all about that.”

While his novels were popular with readers, Pratchett’s work was often dismissed by critics. He wrote that the feeling of “somehow being inferior” picked up during his school days had stayed with him and was “hard to shake off”. But his anger, he said, carried him “quite a long way”.

During his later years, the writer campaigned for terminally ill patients to have a right to die, and featured in a documentary in which he followed a man with motor neurone disease to the Swiss clinic Dignitas to watch him take a lethal dose of barbiturates.

Last year, fans travelled from around the world to gather at the Barbican Centre in London to pay tribute to Pratchett a year after his death.

A TV adaptation of Pratchett and Neil Gaiman’s novel Good Omens was recently picked up by Amazon Studios. It is scheduled for worldwide release in 2018.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion