All you need to know about Scotland's council tax system

- Published

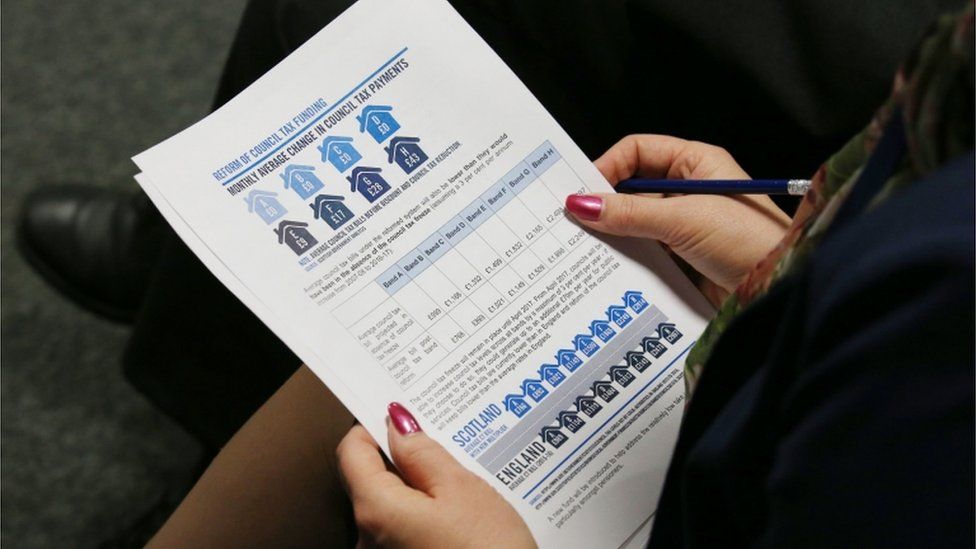

Scotland's local authorities are setting their budgets for the coming year, including decisions on whether or not to raise council tax. So what could be decided, and what could happen to your bills?

What are councils deciding?

Each council has the option this year to raise the basic rate of council tax by up to 3%.

This means rates for all properties could rise above the level set in 2007 for the first time, with the end of the government's long-running council tax freeze policy.

The government funded the freeze with £70m, but that cash also acted as a form of enforcement, with councils risking losing their share of the pot if they increased rates.

Now, councils have more of a free hand - but only up to a point.

Decisions on whether to raise rates or not are down to each individual council, as they set their budgets for the coming year.

So far, some have indicated they will go for the maximum 3% hike, while others have suggested they might voluntarily continue the freeze.

Politics, as ever, will play a major part, especially with council elections looming in May - arguments will abound in town and city halls about "passing on austerity" to taxpayers, preventing cuts and protecting local services.

Why are some bills going up regardless?

If you live in a property in a higher band - anything from E up to H - then your council tax is going up, no matter what your local authority decides to do.

This is because MSPs voted last year to increase the multiplier for the top four rates from April, which should raise £100m extra each year.

Town halls set the rate for band D, and the other rates are then calculated as a percentage of that; so at present band A properties pay 67% of the band D rate, while band H ones pay 200%.

What the changes boil down to is that the average band E household will pay about £2 per week more than previously, while the average band H household will pay about £10 a week more.

That increase is on top of whatever increases to the band D rate that councils decide on.

The cash raised from this was originally going to be distributed to schools across Scotland, but this idea sparked an almighty political row over local taxpayers' funds being spent on national priorities - to the extent that the final order passed at Holyrood included lines condemning the government for "undermining the principle of local accountability".

By the time the budget rolled around, the government had relented, and the £100m raised will now be spent locally - but schools are still getting the extra funds, as Finance Secretary Derek Mackay has found cash elsewhere.

How many households will this change affect?

Of Scotland's almost 2.6m homes, almost 700,000 are in the top four bands - in total, 26% of households will see their bills rise regardless of what their councils decide.

The changes to the upper bands will affect some areas more than others.

In East Renfrewshire, there are 20,950 properties in the top four bands, to 17,012 in the bottom four. This means the majority of households, 56%, will see a jump in their bills. On top of that, councillors have decided to raise all tax bands by 3% - the maximum the government has decreed.

But if you contrast East Renfrewshire to what is happening in one neighbouring authority, East Ayrshire, you will find 47,514 properties are in the bottom four bands, while only 10,466 (18%) are in the top four. So here, most properties will only be affected by the decisions taken locally.

This disparate picture is equally reflected in Scotland's cities; in Dundee only 14% of properties fall in the top four bands, compared with 37% in Edinburgh. In Glasgow it's 16%; in Aberdeen, 27%.

This affects the amount of cash each council will raise due to the changes - in Edinburgh it is projected to be more than £15.6m, while in Glasgow it will be about £6.7m, despite the larger population there.

Is my property in the right band?

For a slim majority of properties, studies have suggested that the answer is no.

The current council tax banding system is based on property values as of 1 April, 1991.

This can lead to some rather strange circumstances, as prices have changed more in some areas than in others since then. Indeed, some council taxpayers weren't even born when the tax values of their homes were determined.

Green MSP Andy Wightman pointed out during a recent debate that one of his Edinburgh constituents lived in a flat in band E, which was worth £20,000 less than neighbouring flats which were in the cheaper Band B.

An analysis by the Commission on Local Tax Reform in conjunction with Heriot-Watt University suggested that 57% of properties would have changed band had a revaluation been carried out in 2014, with roughly an equal number moving up as moving down. Most would have moved a single band, but a few could have jumped (or slumped) two or even three.

There has been some opposition support for a revaluation. However, the government argue that it would cost up to £7m, take several years, and could result in "a shock to the system", with "significant and dramatic" changes to bills.

What has this got to do with the government's budget?

While a good amount of cash is raised from the council tax, local authorities rely on the government for the bulk of their money. For example, Glasgow City Council raises 17% of its budget from taxation, with 83% coming in government grants.

Predictably, there has been a political row over exactly how much money will go to councils under the budget currently passing through Holyrood.

Derek Mackay's original plans were for a cut to the core grant, the money actually going in to council coffers. But he offset that with extra funds going directly to local services, like attainment fund cash for schools and investment in health and social care partnerships, arguing that this meant the total for "local services" was actually going up.

The deal he eventually sealed with the Greens included an extra £160m in direct local authority funding. Again there is disagreement over whether this alleviates the planned reduction in core budgets.

Labour say there is still a £170m cut, while Green co-convener Patrick Harvie argues the deal he struck takes allocations from "a severe cut" to "just about good enough".

Also factored into some strategic budget calculations was the potential rise in council tax - the government postulated that £70m could be raised in total if all councils used the maximum 3% raise, although it now appears that will not be the case.

- Published2 March 2017

- Published2 February 2017

- Published3 November 2016

- Published5 October 2016