Balancing her baby daughter on her lap, Leah* sits in a bright room on the top floor of an East London office block. It’s a lively part of town. Newly built luxury flats tower over streets lined with decades-old black beauty shops, one-stop mobile phone stalls. The storefronts of family-run greengrocers are piled high with yams and bowls of okra, peppers and coriander.

Leah is waiting to get help and advice from Latin American Women’s Aid. They’re a small charity challenging violence against women and working with survivors of domestic abuse. They rent three rooms — one for an office, a crèche space for children and a place to see women.

Lawa, as the group is widely known, opened in 1986 and they run the only domestic violence refuge for Latin Americans in the UK. Like other refuges and organisations set up in 70s and 80s Britain, they arose from radical women’s rights and anti-racist movements. Domestic violence shelters specifically for black, south-Asian, Chinese, Latin American and other ethnic minority women, now bundled under the term BAME, were founded because these women weren’t getting support from statutory or mainstream places.

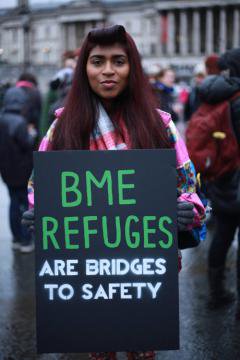

Sisters Uncut block city bridges across the UK ahead of govt. spending statement. Photograph: Guen Murroni. All rights reserved.

Decades on, by the time the Coalition government made deep cuts in public spending in 2010, many BAME domestic violence organisations, including Lawa, relied on council funding to pay for part, if not all, of what they offered. Bed spaces, English as a second language classes, counselling, childcare, time intensive advice work, court assistance.

But in the past six years, cash-strapped local authorities have cut back frontline domestic violence services, diverting money from small specialist providers and awarding contracts to larger organisations making promises to deliver more for less money.

Each year Women’s Aid surveys the state of refuge and service provision, each year the numbers are worse and each year brings news of another refuge closed.

Then, last month, in response to the worsening crisis, the government released a £20m pot of funding for local authorities to bid for, in partnership with local specialist domestic violence providers. “Domestic abuse knows no barriers,” said Communities Secretary Sajid Javid. “It can happen to anyone of us, at any time. Our £20 million fund is designed to increase refuge spaces and ensure that no victim is ever turned away from the essential support they need.” The government said the fund was “also seeking to address the needs of diverse communities, including BME victims and those from isolated communities, so they can access support and help.”

But there’s a problem.

It is a Tuesday when Leah visits Lawa’s drop-in session, and already she is dreading the weekend. Leah is 25 and lives in a two-bedroom flat with her husband Gabriel*, her baby and four other adults.

Alejandra, one of Lawa’s case workers, sits across from Leah, taking notes at a table between them.

Behind Alejandra, there’s a colour photo of the Mexican painter Frida Kahlo and a poster: “Unity, Strength, Resistance” splashed on red. Across the room Rosie the Riveter has been refashioned into four women: black, Spanish, white and Native American. The caption reads, Si, Se Puede! A Post-it note stuck to a cork noticeboard says, “Hey you don’t give up. Okay.”

Leah tells Alejandra that she needs housing advice— that’s the purpose of her visit. But as Alejandra listens, another story emerges.

Originally from Guatemala, Leah and Gabriel have lived in the UK for little over a year. Like nearly half of all Latin American migrants in London, Leah’s husband took an unskilled job. He cleans nine hours a day, and earns roughly £1,300 each month. Most weekends he drinks heavily, using alcohol to ease the disappointments of their life in London.

Leah smiles and bounces her four-month old daughter on her lap. “He is a good man,” she says. “He is a good dad. It is just that the alcohol makes him aggressive.”

Alejandra asks: “Are you frightened?”

“No.” Leah shakes her head, still smiling. He is frustrated, she adds, the housing situation is unbearable and the family struggle to survive on his wages.

It’s a familiar story to the women running Lawa. Men forced to work long hours in menial, ‘feminised’ jobs, become violent and abusive towards their wives.

In Leah’s case the abuse is verbal. Malicious comments, name calling, heated arguments over money. Except the one time he grabbed her by the throat.

Waterloo Bridge, London. Photograph: Guen Murroni. All rights reserved.

Between 2001 and 2011 Britain’s Latin American community grew fourfold. And though Latin Americans are not officially recognised as an ethnic minority, they experience the harassment, employment discrimination and problems that affect other minority groups in the UK.

There are high employment rates for Latin Americans in London (85 per cent compared to the average for other foreign-born residents, 55 per cent), but much of that work, around 70 per cent, is concentrated in cleaning, hospitality and catering, despite professional training and experience acquired in their home countries.

They face discrimination at work, 11 per cent are illegally paid below the minimum wage and the majority send a significant chunk of their low incomes back home. As with other poor and even middle income households in London, it is impossible to find decent housing, close to the centre where many of them work cleaning corporate buildings.

These are the conditions revealed through research by Trust for London in the 2011 report No Longer Invisible. Few Latin Americans in London access public services, the report says, one in five never visit a GP. The restrictions on legal aid for poor migrants means few can get legal advice to regularise their migration status to access the full range of rights citizens receive. Settling into British life is difficult because of the unsociable hours in the typical jobs available, like cleaning and hotel work. English as a second language lessons are most likely to be during work hours or when people need to sleep because they work nights.

When a woman in this community faces domestic violence, her experience intersects with the other problems she faces as a disadvantaged minority. The threat of homelessness, poverty, childcare, immigration, language needs, among other things. Around 600 women and non-binary people took part in Sisters Uncut actions in Newcastle, Bristol, Glasgow and London. Photograph: Guen Murroni. All rights reserved.

This is where Lawa comes in. “The language barrier is almost the smallest issue women face if they go to a generic service,” says Salma, Lawa’s senior development officer. She adds: “The most important thing is that when they come through our doors, they are believed, culturally understood and properly supported, rather than judged and discriminated. BME services play a key role in building a bridge between BME survivors, local services and the wider British society. In our last user survey, 85 per cent of women did not feel confident enough to access mainstream services prior to seeing Lawa.”

Lawa has changed over the years as more Latin Americans have arrived in London, mostly from Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Bolivia and Peru, and often via Portugal or Spain. As Home Secretary, Theresa May promised to create a hostile environment for migrants, and migrant women fleeing violence were no exception. Many of Lawa’s cases are “European Economic Area cases”, that is Latin American women with an EU passport from Spain or Portugal. Lawa sees women who flee to the UK after some sort of crisis, abuse by a relative or spouse. Or the women might be living in the UK on a spousal visa, linked to their husband’s British/European Economic Area status.

In both cases Home Office rules restrict their access to public services, which means they are more likely to be destitute, homeless and vulnerable to exploitation and further violence. Women can apply to have the restriction lifted, but the threshold for proving violence and destitution, thus entitling them to public support, is high. The recent changes to immigration law have created a culture of suspicion among public sector professionals who aren’t always sure what foreign born women are entitled to and so lean towards refusing services or charging for it.

One of Alejandra’s clients lives in the UK on a spousal visa. Originally from Colombia, she is married to a British man. He’s ex-Army, has access to guns that he uses to threaten her. She wants to leave, but her spousal visa comes with the condition that she has no recourse to public funds.

Alejandra found a bed for her at a shelter that accepts ‘no recourse’ women. She is lucky; there are few such refuges in the country. The next step is securing a non-molestation order to prevent the husband from contacting her. This is expensive — they’ll need legal aid. Even then, it’s a tall order. She’ll need to prove destitution and provide evidence of the domestic violence. This involves gathering and collating GP letters, a marriage certificate, passport, bank statements and evidence from the refuge. If and when legal aid is secure, Alejandra can go ahead and apply for the non-molestation order. All this could take weeks.

“Working with women who have no recourse to public funds is tough,” says Victoria, Lawa’s violence against women and girls coordinator. “What happens after the initial help? There are so few places we can send the women to. There aren’t many organisations that work with no recourse women, so we have to do the work ourselves. But we are a small charity with limited capacity and can’t indefinitely support the neediest women with no extra funding.”

On the day of Leah’s visit, Victoria is working across the corridor in Lawa’s office on the phone, trying to reach a local GP. Other Lawa staff dash in and out, speaking in Spanish and English, to each other and on the phone to clients. Camilla, Lawa’s counsellor, has just secured a grant to expand the charity’s mental health support next year. Nayane, originally from Brazil, rushes out to help an Angolan woman, who has arrived with letters from the Department for Work & Pensions stopping her grandson’s Disability Living Allowance. She is his sole carer and unsure of what to do next. Nayane gets on the phone to the DWP.

Victoria shushes her colleagues as the doctor answers the phone. He wants £20 for a letter explaining the domestic violence Victoria’s client has experienced. “My client has nothing,” Victoria tells me later. “She was totally dependent on her husband.”

Without the letter, they might not secure legal aid, which the woman needs to fight her husband in the family courts for custody of their children. In the worst cases women are deported, made homeless or forced to stay with their abusive partner.

"You block our bridges, so we block yours." Rallying cry at feminist direct action protest against cuts to DV services. Photograph: Guen Murroni. All rights reserved.

More women than ever need help. Lawa can’t keep up. Two years ago, Islington Council stopped funding Lawa’s work. “Since then we have been struggling to balance the books,” says Salma. “We continue to provide the service by going above and beyond, but there is great insecurity. We don’t know how much longer we will be able to provide the service women deserve without additional funding.”

About that £20m funding pot from the government. The design and structure of the commissioning process may block access to the groups who serve “BME victims and those from isolated communities”. Groups like Lawa.

Earlier this year, research among charities based in London where around 40 per cent of the population is from an ethnic minority, revealed a profound lack of trust in the people who commission services. Imkaan, a black feminist network of violence against women and girls organisations, reported that many of its members felt local commissioners did not recognise the importance and necessity of BAME services.

In England last year 662 women were turned away from domestic violence refuges because they had no recourse to public funds, up from 389 the year before. These women would have already been denied access to social housing, benefits or legal advice because of their status. There are no safe places for them to flee to. “The women we work with are victims twice over,” says Victoria. “First of domestic violence and then of the system's refusal to help them.”

One of Sisters Uncut demands is comprehensive DV services for all, especially underserved communities of black and brown, disabled and LGBT+ survivors. Photograph: Guen Murroni. All rights reserved.

In May, MPs held a parliamentary debate about the future of

domestic violence refuges. Labour MP Julie Cooper called the debate todiscuss

the lack of ring-fenced funding for women’s refuges. Cooper directed her plea

to George Osborne, the then Chancellor responsible for orchestrating

Conservative spending cuts, said: “At the end of every cut he makes to local

authorities, there is a woman who will die, avoidably, at the hands of a man

who once promised to love her. Cuts to public spending are creating orphans who

could have grown up with parents. I beg the Minister to ensure that this

Government do not unravel 40 years of good work. I beg him to listen and to act

without delay.”

More than one politician said they feared BAME specialists services would not survive. Sarah Champion, Labour MP, spoke up for Lawa and for Apna Haq, a small domestic violence charity in her own constituency of Rotherham. “Such dedicated services are vital for women,” she said. “They are experts in their provision, designed and delivered by, and for, the users and communities they serve. The women who seek shelter see themselves reflected in the staffing and the management of the services.

“ … specialist services are trusted by the women who use them. Their presence is known in the community, meaning that women will self-refer, enabling those women to leave a violent relationship because they know that support exists.”

But what if that support is taken away?

Leah’s interview with Alejandra lasted about 25, 30 minutes,

long enough to squash any dream of finding a rented flat for just herself, her

husband and daughter by in London. “It’s going to be very difficult to find

somewhere to live, especially on his wages,” Alejandra said. They might qualify

for housing benefit, but they need to find a place to live first and a contract

before applying. “It is impossible.” A look on Leah’s face suggests she knew

this. She smiled, then more questions. If I go back to Guatemala without

telling him? What will happen? And then: I would like to divorce him. A divorce

would invalidate her right to remain in the UK. Leah gets up to leave and puts

her daughter into her pushchair. She plans to come back to Lawa for the free

English lessons. Alejandra has told her about a service in north London for

families with drug or alcohol problems, the couple should attend together. If

your husband refuses, she says, “Call me.”

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.