This month, two books, alike in dignity (and indignation), examine how women have succeeded in the arts and sciences, often through channels men weren't interested in taking. The first, The Glass Universe: How the Ladies of the Harvard Observatory Took the Measure of the Stars (Viking), by best-selling science writer Dava Sobel, is the little-known story of a group of remarkable female "computers" (their roles began as simple math-oriented clerking; many were relatives of male scientists) employed by the Harvard College Observatory beginning in the 1870s. An early scene from the book provides so perfect a metaphor for Sobel's narrative that it reads almost like fiction: In 1878, amateur astronomers Henry Draper and his wife, Anna, traveled to the Wyoming Territory from their home in upstate New York to witness a rare total solar eclipse. But, Sobel writes, "during that memorable interlude of midday darkness," while the men on the excursion, Thomas Edison among them, observed the phenomenon, "Mrs. Draper had dutifully called out the seconds of totality (165 in all) for the benefit of the entire expedition party from inside a tent, where she remained secluded, blind to the spectacle, lest the sight of it unnerve her and cause her to lose count."

Heaven forbid that Mrs. Draper—an heiress, her husband's collaborator for 15 years, and the woman who went on to significantly fund the Harvard astronomy program after Henry's early death—be unnerved. In The Glass Universe, men trek into the wild to photograph the sky; women scrutinize the mathematical minutiae—from tents, and desks back in Cambridge—for answers to questions about space and time. Sobel (author of Galileo's Daughter) writes about more than a dozen of these pioneers. One, Cecilia Payne, in 1925 became the first female recipient of a Harvard PhD in astronomy, with a thesis about the composition of stars that, as Sobel notes, "challenged the very fabric of the universe." By specializing in the elegantly abstract—literally, space and time—they carved places for themselves in scientific history.

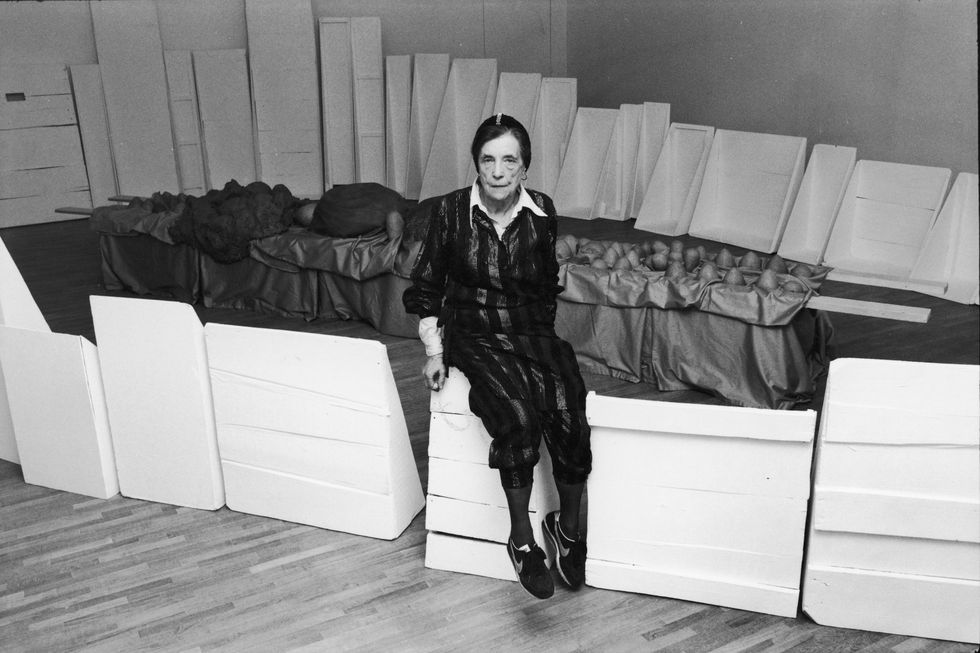

Brilliant women finding ways around macho constructs in science and art—and turning them to their advantage—is also the topic of novelist and essayist Siri Hustvedt's new essay collection, A Woman Looking at Men Looking at Women (Simon & Schuster). Unlike Sobel's biographical history, Hustvedt's book is a psychosocial commentary and critique, its scope ranging from the racial and sexual politics of hair, to epigenetics, to art criticism. (She is also a lecturer in psychiatry at Weill Medical School in New York.) In one essay, "Balloon Magic," Hustvedt compares a complex, innovative sculpture series by the twentieth-century artist Louise Bourgeois to Jeff Koons's giant orange balloon dog. For decades, Hustvedt writes in a later piece in the book, "Bourgeois stayed home and made sculptures." Hustvedt likens her to Emily Dickinson, who stayed home and wrote poems; I was reminded of the female computers inside their observatories, reading photographic plates. But Bourgeois saw her period of seclusion as good luck. After years honing her craft out of the limelight, in her late seventies she finally began receiving recognition—as Hustvedt says, "blasting out into the world."

Hustvedt draws a searing analogy between Bourgeois and Koons. For his Clifford-esque cartoon sculpture, Koons commanded $58.4 million from an anonymous buyer. Playing a statistics game, Hustvedt assumes the buyer was male: Men purchase the most expensive art, and because the ownership of art acts as an extension of the self, they tend to buy male artists, driving up those prices in a costly game of chicken-and-egg. Last year, Bourgeois set a record for the highest price paid for a sculpture made by a woman when one of her bronze spiders sold for $28 million.

"The 'feminine' has far more polluting power for a boy in our culture than the 'masculine' has for a girl," Hustvedt writes in another essay. Women read books by men and wear pants—and make massive bronze sculptures. Men are far less likely to read books by female authors…or wear skirts. Because of this bias, Bourgeois (like other female artists) "had to forge a trajectory for her art from another perspective," Hustvedt writes; whether painting or printmaking or the sculptures for which she's best known, her work is startling in its originality. "As [Bourgeois] said, 'The art world belonged to men.'"

At face value, Bourgeois's artistic pursuits might seem, well, light-years away from the work of the women at the Harvard College Observatory. But in reading Hustvedt's essays, I was catapulted back to those early Harvard women, barred from the rugged adventurism their male colleagues reveled in. The work of observation itself was deemed "too uncomfortable, too cold" for women, Sobel says, "not to mention [the taboo of] being out at night with these men." Yet still they found their way into space. Twenty-eight years after a Harvard professor named Edward H. Clarke cautioned in his book, Sex in Education: A Fair Chance for Girls, that intellectualism in girls could lead to shrunken uteri, neuralgia, hysteria, and insanity, Harvard astronomer Henrietta Leavitt published a 1912 study proving that certain stars ("Cepheid variables," named for their regularly fluctuating brightness) could be used to calculate distance in space up to 10 million light-years, 100,000 times farther than what was previously possible. In time, Leavitt's work helped calculate not only the size of the Milky Way, but something nearly incomprehensible—the age of the universe.

This article originally appeared in the December 2016 issue of ELLE.