Once upon a time there was a Greek, an Englishman, a German and a Spaniard. They decided they would each write a story that would do its best to explain the human condition. The Greek said, I’m going to write about a man who’s tossed about on the seas after a war and when he finally returns home, no one – not even his wife – recognises him. The Englishman said, I’m going to write about a young, indecisive prince who can’t decide whether life is worth it. The Spaniard said, I’m going to write about a prevaricating farmer who believes he’s a knight and sets out on his rickety horse for a series of madcap adventures. The German said, I’m going to write about a young man who falls passionately in love with someone else’s wife and dies of love in the end.

If we look at things schematically, that’s more or less how Homer created the epic, Shakespeare the drama and Cervantes the novel of wanderlust, while Goethe cultivated the soil of romanticism. It could be a joke, but it’s the history of European literature. And the strange thing is, these characters after whom every modern and postmodern narrative follows are themselves deeply modern: marginalised antiheroes. Today we recognise them and meet them in the light of their popularity, their interpretations and distortions, but who are they really? What do the people around them think of them? And what do they think of themselves? What image does literature give us about the dreams and quests of Europeans and their ancestors?

Let’s take Odysseus as an example. Before he reaches Ithaca he washes up on the island of the Phaeacians, naked and in despair. He resembles the contemporary refugees who have been arriving on the shores of Greece. In the eyes of Nausicaa and her companions, he seems terrifying. “Like some hill-kept lion, who advances, though he is rained on and blown by the wind, and both eyes kindle; he goes out after cattle or sheep, or it may be deer in the wilderness, and his belly is urgent upon him to get inside of a close steading and go for the sheepflocks. So Odysseus was ready to face young girls.” Urgency – what a prophetic word. And how contemporary it sounds today, in light of the refugee crisis. Even mythical Odysseus can only assume his position as hero once he has washed and put on clean clothes.

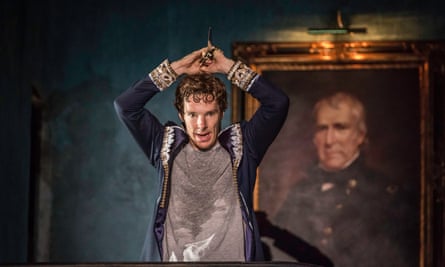

But Hamlet, too, seems bizarre in the eyes of Claudius and Gertrude. And Don Quixote is a madman to the villagers he encounters: when they ask him why he’s wandering around in armour during peacetime, he presents himself as a “wandering knight”, an ambassador of God on earth. Goethe’s Werther is crazy with love, and sends his servant to Lotte’s house merely so he can have someone close by who, he says, “has been close to her, too”.

The characters in these books who encounter those paradigmatic heroes as lovers, rivals, servants, friends or random passersby think the way we have been taught to think when we encounter something unusual, exaggerated or foreign: Odysseus is a filthy shipwrecked sailor, Hamlet sees ghosts, Don Quixote is walking on clouds and Werther is ruled by an unhealthy passion.

What literature does is incorporate the other in all its quirks and peculiarities into the social body. It allows for difference, and often even proclaims it to be genius. It considers difference a sign of courage: the hero is who he chooses to be. Or he fights for his freedom, his ideas, or his aesthetic, as does James Joyce’s Stephen Dedalus in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.

Fiction teaches us to think creatively about difference. Anthropological studies, psychoanalysis, sociology – all offer theoretical descriptions for what a novel teaches by example and by identification. “The imitation of an action”, is what Aristotle called tragedy. It would be difficult for one to think up a more groundbreaking mode of understanding the mind and the heart. Guilt, jealousy, despair, violence, anxiety, irrationality, the fear of death – nothing that is human is foreign to literature. So the more education falls into decline because of a lack of imagination (not to mention funds), the more literature is called on to serve as another form of education. When we read the emblematic works of the European tradition we begin to trace the outlines of a coded, radical understanding of the other. Unconsciously we begin to accept that the other is always a mystery and that easy characterisations lead nowhere. Imagine if Odysseus were nothing more than a filthy, shipwrecked man. And think just how much we learn from his arrival on the island of the Phaeacians about the people arriving every day on Europe’s shores.

If we leave the treatment of the refugee crisis to the mass media, if we forget the shipwrecked men of literature – from Odysseus and Robinson Crusoe to Michel Tournier’s Friday – we’ll remain trapped in the stereotypes of refugees as a homogeneous mass of people who have come to tyrannise the west. Literature transforms amorphous fear and pity into individualities. It tells us: the other is not what it seems.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion