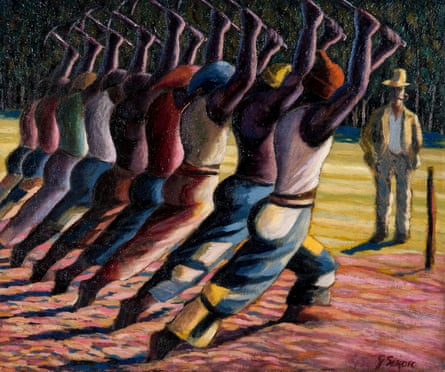

Can war be beautiful? It was undoubtedly an art of sublime elegance for the Zulu nation in the 19th century, when they used some of the most precise military manoeuvres ever planned to massacre an entire British army.

The Battle of Isandlwana in 1879 shocked and perplexed the Age of Empire. Warriors equipped mostly with spears and ox-hide shields should not have been able to destroy a European force armed with Martini-Henry rifles, it seemed to Victorians.

In the British Museum’s thoughtful and illuminating new exhibition about the art of South Africa, two spears found in the body of Lt Edgar Oliphant Anstey after the battle are on display next to a pair of bull’s horns engraved with scenes from the Anglo-Zulu war. Bulls inspired the Zulu art of war. Their devastating strategy at the Battle of Isandlwana was called “the horns of the bull”. Two flanking armies of the youngest, fastest-running warriors – the “horns” – surrounded the British and drove them back against ranks of seasoned soldiers waiting for the kill.

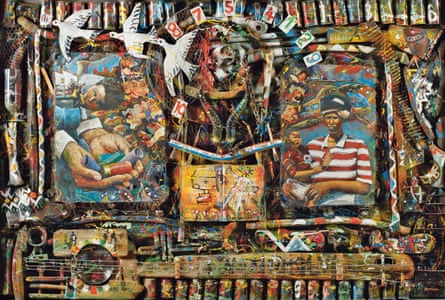

It’s difficult not to side with the Zulu. Their military genius is a moment of glorious payback in a history dominated by white exploitation, rapacity and racism since the Dutch settled at the Cape of Good Hope in 1652. Johannes Phokela cleverly pastiches 17th-century European art in his painting Pantomime Act Trilogy (1999): child soldiers wearing Comic Relief red noses and the rotting bodies of colonial forebears inhabit baroque architectures painted in grisaille. Phokela’s surreal painting captures the strangeness and macabre violence of the history this exhibition resurrects.

South Africa: Art of a Nation tells the longest story of art any nation can claim. The oldest exhibit here is 3m years old. It is a pebble with a face. The way it looks is accidental. Its two eye-like holes and slit of a mouth were cut by natural erosion. So what makes it art? An australopithecene – an early hominin – picked it up and carried it home, apparently because of the way it looked. It is a found portrait, a ready-made image of the proto-human face.

The centrality of southern Africa to the evolution of human life would make an exhibition in itself, and encompassing it within a chronological survey of art up to the present day might seem a bit glib. Yet something grabs this exhibition, shakes it, and fills it with rage. History infects it. Far from being a benign celebration of South Africa’s arts, it is a story of human struggle and sacrifice.

Is Sam Nhlengethwa’s collage drawing of the death of Steve Biko a great work of art? Who cares? This moving work of protest remembers one of Apartheid’s most arrogant murders. It also does happen to be very good art, but this exhibition also defines art to include Nelson Mandela badges, a plate decorated by a Boer prisoner in a British concentration camp, an anti-apartheid calendar and Gandhi’s sandals.

It is the story of South Africa’s people, and art here means all their forms of visual expression. A wooden statue of Christ playing football, carved by Jackson Hlungwani in 1992 for the church he founded on a hilltop in Limpopo, has as much place here as masterpieces of pre-colonial art such as the Lydenburg Head, a powerful mask-like terracotta portrait made some time between AD 500 and 900.

One of the most addictive exhibits is a slideshow by Santu Mofokeng called The Black Photo Album. Mofokeng researched a forgotten – a deliberately denied – history of black South Africans who were photographed in the 19th and early 20th centuries in European middle-class dress and houses. These people should not have existed, according to the apartheid version of history he was taught at school.

European and “Bantu” were supposedly opposites, yet these portraits reveal a much more mingled and mobile society in the days before apartheid imposed its racist doctrine.

As a white South African today, Candice Breitz feels like an invisible spectator to a future she cannot help to build. That is how she represents herself in Extra!, a video-art soap opera about the new South Africa in which the black actors ignore her ghostly presence standing behind them, or lying on the floor, watching passively.

Mary Sibande, meanwhile, portrays herself as a purple octopus of hope, a new creature in the world, an empowered black South African woman.

It is in this context of a new nation freed from apartheid that South Africa has become aware of its deep art history. For the scale of the story told here reflects a nation’s emerging self-consciousness. It was in 1987, with apartheid in its bloody final years, that anthropologists identified an African “Eve”, whose mitochondrial DNA is shared by all living humans.

Since the 90s, as South Africa became a democracy, the thesis that our species, homo sapiens, evolved in Africa grew from a controversial theory to one that is today accepted by almost all prehistorians.

That makes the earliest things on this show among its most contemporary, for today’s South Africa can and does claim to be where art was born. It stone-age art is not the property of one racial group, but all humans. It gives South Africa a special pride, for this place that has seen so much sorrow is the cradle of us all.

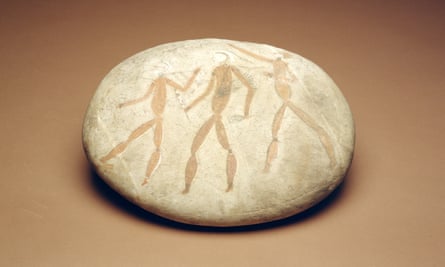

The Blombos Cave beads on view here bear witness to that common past. About 75,000-78,000 years ago, homo sapiens like us painted these beads with ochre at a cave where painting tools and a piece of ochre incised with abstract patterns have also been found. These tiny stained seashells come from the dawn of art as we know it. More than 40,000 years later, descendants of the Blombos artists painted animals in red ochre on the walls of ice-age caves.

In 19th-century South Africa and the Kalahari, hunter gatherers known as the San people still painted the animals they hunted. The greatest work of art in this exhibition is a two and a half metre-wide slab of rock on which San artists painted a herd of eland. The red and white bodies of the antelopes are shaded with infinite subtlety. The Zaamenkomst panel, as it is known, is one of the masterpieces of humanity. It ranks with the greatest cave paintings of ice-age France as a miracle of observation. Yet San nomads imprisoned in 19th-century Cape Town as “vagrants” said they did paintings like this while in a religious trance. Today, their mystical creative journeys into an otherworld inhabited by dream animals are redefining the origins of art.

This exhibition is as stirring as South Africa itself – a journey to the heart of our common humanity.

- South Africa: The Art of a Nation is at the British Museum, London, from 27 October until 26 February 2017.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion