Realistically, there is only one way out of our predicament.

We know that we live in an age of staggering economic inequality. The top 10% of earners now take in nearly half of all our national income, a portion that has been rising steadily since the Reagan era. Meanwhile, the average income of the bottom 90% has scarcely risen at all during that same period. In this regard, the United States is nearly the most unequal developed nation in the world. When inequality gets this severe, dramatic things start to happen. Revolutions, wars, violent nationalism, instability, the rise of people like Donald Trump—all of these things are in line with what history tells us is in store if we do not reverse the direction of inequality in this country.

Think for a moment about the realistic options for reversing these decades-long trends. The wealthy will obviously not voluntarily surrender their gains. That means there are only two ways to begin putting a larger share of earnings in the pockets of the poor and middle class: The government can take measures to make it happen, like raising taxes on the wealthy, more stringently regulating the financial industry, and strengthening the social safety net; or, lower and middle class workers can assert their own power to claim a larger share of the pie.

I am all for the government taking measures to tax the rich and fund the poor and generally strike blows against the excesses of our system of capitalism. And I suspect that our laws will move in that direction in the very long term, out of necessity. But I do not recommend holding your breath waiting for that to happen. Since the problem is pressing, that means that it is up to the people themselves to do what they can to make our nation’s economy more fair.

There is only one meaningful way for regular workers to do this: unions. Studies have shown that union members earn wages that are significantly higher than non-members—10% to 20% is a reasonable estimate of this “union wage premium.” Furthermore, industries that have high union density see wages rise even for workers who are not in unions. This is all, if you give it a moment’s thought, common sense. Unions enable the majority (workers) to assert their bargaining power. Employers may be able to push wages down against individuals, but they cannot forever push wages down against workers who are organized as a group; ultimately, employers need employees in order to exist.

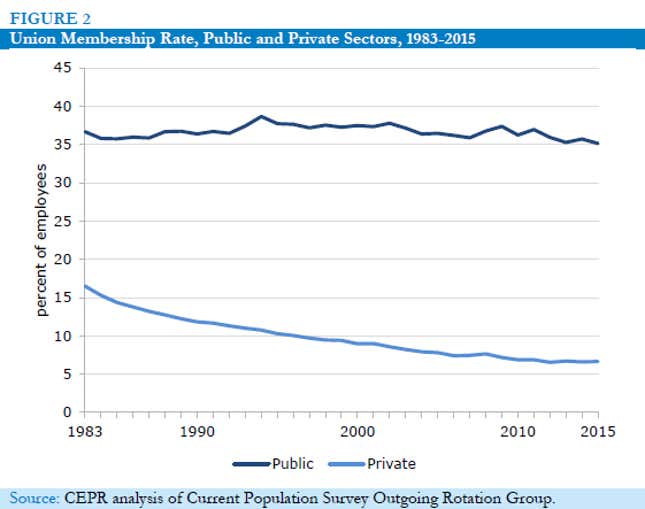

Even though unions are the best tool that normal people have for getting a fairer income, they have been on the decline during the same time period that inequality has been on the rise. This is not a coincidence. In the 1950s, American union membership peaked, with more than one in three workers in a union. Today, only one in nine American workers are in a union; if you take away public sector workers, that rate falls to less than 7%. Here is a picture of the union membership trend since our modern era of inequality began in earnest:

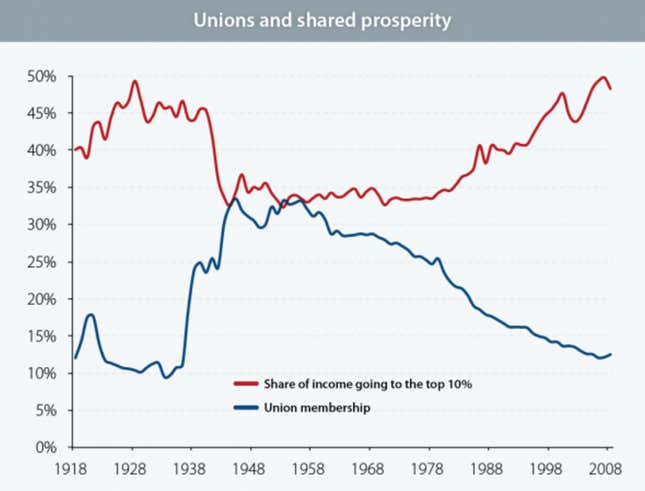

Here is a striking image of how the decline in union membership correlates with the broader rise in inequality:

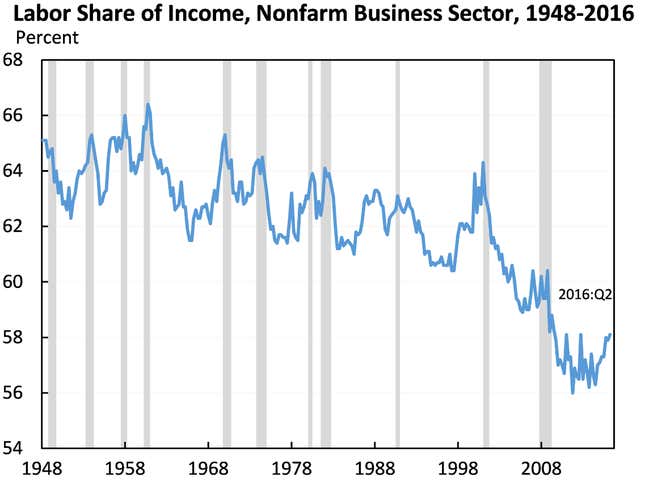

And here is the consequence: a sharp decline in the labor share of income, which is the portion of all national income that goes to worker wages.

This is inequality writ large. Increasing this labor share of income is, broadly speaking, what it would mean to decrease inequality. It would mean more money for workers and a smaller share for the richest slice of people who live off of capital. By one estimate, the decrease in labor share of income over the past 15 years has cost regular workers $535 billion.

Workers who are not unionized are leaving money on the table. Because they lack the ability to bargain collectively, they are getting paid thousands of dollars per year less than they could be. Where are those thousands of dollars per year going instead? Into the pockets of executives and investors. And so inequality grows. Simply by unionizing, you can put that money back into your own pocket. Add ten or 20 or 30 million new members into union ranks and you will see the long climb of inequality turn around. This is the tantalizing promise of what can be accomplished if we can significantly increase union membership in America.

Union membership is an idea that is so obviously beneficial to workers that they will embrace it when they are given an honest opportunity to do so. It sells itself. Yes, there has been a great deal of anti-union propaganda since the Reagan era, but that can be dispelled with simple facts, if organized labor cares to take the time to do it. The great advantage of unions as the solution to inequality is that they are not as susceptible to being crushed by a flood of opposition money as politicians are. The rich can influence Congress a great deal with super PACs, but there is a limit to the quality of lies that corporations can tell about why an employee should not take a simple step that will surely benefit them financially for years to come.

So all we need to do is to get busy organizing those tens of millions of new union members. Right? Unfortunately, organized labor has to a large extent allowed itself to be wooed into prioritizing electoral politics over new organizing. (This very dispute over priorities caused a major rift in the union world ten years ago, leading several big unions to leave the AFL-CIO and form their own coalition called Change to Win, focused more on organizing.) Labor unions have spent more than $100 million already on the 2016 presidential election campaign, more than double what they spent in 2008. While there can be no doubt that Democratic presidents are a worthwhile investment for unions, it is worth asking whether unions have allowed themselves to get trapped in political quicksand, as an increasingly small share of workers spend an increasingly large amount of money in a desperate effort to stave off what they perceive as political doom. Electing Democrats is a recipe for stasis, not progress, and union membership numbers bear this out. (Electing Republicans is a recipe for faster decline.) The Democratic Party will be happy to take and more and more money from unions, unto infinity. But unless unions can start adding instead of losing members, that spending trend will eventually hit a wall.

In 1956, the AFL-CIO, America’s biggest union coalition, had about 13 million members. The population of the country at that time was 169 million. Fifty years later, when our population had grown to almost 300 million, the AFL-CIO had... about 13 million members. That tells you everything you need to know about the failure of organized labor to do what it is always supposed to be doing: organize.

We can blame Republicans and their “right to work” laws, we can blame the inertia of unions themselves, or we can blame the distracted American public. It doesn’t matter. The point is that unions need to add a lot of new members. The long-term downward trend of union membership needs to start going up. If we are serious about turning around economic inequality, this needs to start happening fast, because we can be sure that all of the other realistic solutions will only happen slowly. If we are not serious about turning around economic inequality, we will see other social and political changes happening that we will not like one bit. More than forty percent of Americans appear willing to cast their votes for “burn it all down.” Four more years of the same trends will only increase this tendency.

Organizing new members must be the top priority not just of unions themselves, but also of the entire left-wing political activist structure that exists to fight social ills. Most of those ills—poverty, disenfranchisement, lack of social mobility—spring from the very inequality that a vast increase in worker power is capable of turning around. Organized labor should direct its money and resources into adding new members, and other liberal groups should pick up their slack in political donations. Do they need to organize more low-wage workers? Yes. Do they need to organize more white collar workers? Yes. Do they need to build on existing union strength in friendly states? Yes. Do they need to do the hard work of building a presence in union-unfriendly states? Yes. Do they need to break into new industries like tech where unions have little presence? Yes. And speaking of tech, do they need to figure out how to bring a whole generation of young workers into unions even though they have little connection with or affinity for the withered husk of organized labor? Yes. Is all of this easier said than done? Of course. It’s not easy. It’s necessary.

Unionizing new industries and new workers can no longer be seen as a happy rarity; it must be an urgent priority. It must happen because there is no other good option. We are living in the midst of a generation that has never gotten a meaningful raise, a generation in which it is no longer assumed that your standard of living will be better than that of your parents. A check for hundreds of billions of dollars, made out to The Average American Worker, is sitting on the table. The only way to pick it up is to make unions strong enough that they are a broad-based national force to be reckoned with, rather than a special interest. That means hundreds of thousands of new members per year, at minimum. Unions must set aside petty grievances and rivalries and work like single-minded maniacs with one extremely important task: Turning around decades of inequality by making the working class strong once again.

Organize. Or eat your crumbs as the world burns.