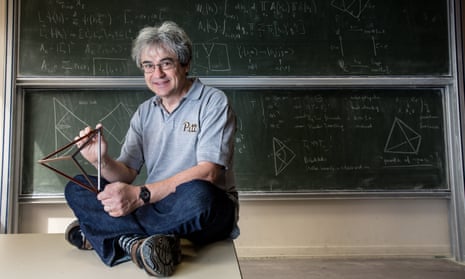

Carlo Rovelli is professor of physics at Aix-Marseille University. He is a pioneer in research into quantum gravity which seeks to integrate Einstein’s general theory of relativity with quantum mechanics, specifically by removing the idea of time. Rovelli’s slim book Seven Brief Lessons on Physics became an international bestseller last year, outselling Fifty Shades of Grey in his native Italy. His new book, Reality Is Not What It Seems, describes the development of physics from classical Greece to the present day. This interview was conducted on the phone with Rovelli at his home in Marseille.

Were you surprised by the great success of your book, of the appetite for theoretical physics?

I did not expect it at all. It is translated in 41 languages. I expected just a few thousand copies sold. I think it is because the book offers a perspective on science that also talks about beauty and emotions – I don’t think those things should ever be separated from science.

You began with a tale of Einstein, before he proposed his theories, loafing around, drifting. Do you think that state of mind is useful for scientists?

I think the great leaps of knowledge are made when one steps back, and forgets, and explores different things. Darwin got on a boat and went round the world and that freed his mind from the thinking in Oxford and Cambridge at the time. If he hadn’t gone on his voyage perhaps he wouldn’t have had the liberty for his discovery.

Do you try to incorporate that freedom in your own life?

I have certainly wandered around a lot. I graduated very late. I was a bad student. I travelled. I did a lot of politics in the 70s. I still try to keep my perspective as open as possible.

I read that back then you experimented with hallucinogenic drugs. Has that helped your thinking on the nature of reality?

I think we are all trapped in our habits of perception in some ways. It is not that you take drugs and you solve physics problems. Not at all! But it maybe helps in losing the idea that what we see is reality.

You have long been trying to prove the idea of quantum gravity. Do you wake up with that goal in mind?

If we could get empirical confirmation it would be fantastic. Nothing is very solid yet, but I am working on some astrophysical signals and trying to connect them with the theory. So I do wake up excited about that. I am 60. Having that kidlike excitement every day is a great privilege.

How long have you lived with that ambition?

I was around 26 when I discovered the idea of quantum gravity. The scale is very small: 10-33 centimetres. One day when I was doing my PhD I took a piece of paper and wrote 10-33 centimetres in red, very large and stuck it on the wall. And that was going to be my aim, to try to work out what was happening at that scale.

The poster must have been a tricky thing to explain to your friends and girlfriends at the time?

Yes and no. My friends saw my passion and I loved trying to explain it.

At the same time you were interested in radical politics in Italy. Were the two things connected in your mind?

I moved from one to the other. I was taken by trying to change the world through politics in the 70s. But in Italy there was a transition from great hope to disappointment in that period. It was at that point I thought there is another place where revolutions happen, and that is in science.

I guess in some ways the complexities of Italian politics made theoretical physics a walk in the park?

Yes, absolutely. Or at least it was a good way into thinking about the nature of reality.

You started a radio station back then?

I was a student in Bologna and we started this pirate station, Radio Alice, like Alice in Wonderland. It was in the centre of town and anyone could come in and talk about what was on their mind. It was fantastic for a while.

It sounds a good model for research?

Yes, science is always a matter of exchange of ideas. It has never been about national borders or whatever. Most of my work is talking and listening to people.

Some of your own collaboration has been with your partner [and former student] Francesca Vidotto. It sounds like a proper meeting of minds?

I have written a book with Francesca but she lives in the Netherlands. All relationships are different but I think ours works very well. She has very different skills from mine, but there are also new things happening, always new things to talk about.

I’m sure you need a degree of optimism to keep looking for answers to complex questions. Are you ever undone by doubt?

My normal day is to do pages of calculations and then throw them away. Part of what I do is accepting that I might have spent my whole life trying to prove a theory that is wrong. I hope it’s right. But you always have to accept the opposite is possible. If you want certainty, science is a bad place to look. But if you want reliability and probability, science is the best place to go.

Do you have a sense of mortality?

I have always had it. I believe our life is just a few numbered years. I am very serene with that. If I died today or tomorrow I would feel I have done what I can. If I have more years and can do more, then great. The more we accept what we are – mortal – the better we can live.

Did you ever have a religious faith?

When I was about 20 I thought a lot about it. And I decided I was not interested in it except as a natural phenomenon. As a philosophy I have been attracted by Buddhism. I think it comes naturally to a scientist in that it talks about impermanence and nothing being solid. I have done some meditation, but I am too busy really.

How do you relax?

I love living by the sea. I have an old sailing boat, 100 years old, very beautiful. If I am stressed I take it out, concentrate on sailing and not falling in the water, and by the time I come back everything is always back in place in my head.

Reality Is Not What It Seems by Carlo Rovelli is published by Allen Lane (£16.99).Click here to order a copy from Guardian Bookshop for £13.93

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion