Here’s a scenario: Katharine Parker from Working Girl (1988), resplendent in shoulder pads, walks into a bar and orders a shot. Draped slinkily on the stool next to her is Lara-from-the-New-York-office from Bridget Jones’s Diary (2001), nursing her own drink. On Katharine’s other side sits Ashley Bartlett Bacon from While You Were Sleeping (1995). After a brief silence, all three raise their glasses to a portrait of their foremother hanging on the wall behind the bar. The woman in the painting, a smug smile playing at her lips, is Caroline Bingley of Jane Austen’s novel Pride and Prejudice.

These three women – all great, all romantic-comedy “bitches” – owe their very existence to Miss Bingley.

She is the wellspring from which more than a century of modern movie rom-com bitches have sprung. She is the prototype. Adversary of Legend, Disparager of Protagonists, Godmother of Modern Rom-Com Bitchery.

And while the romantic-comedy bitch comes colored in subtly different shades in every incarnation (and her race is not insignificant, which adds a new layer to the societal casting of what is bad and undesirable to us), these are largely superficial variations of the trope. We were indoctrinated early: How else to explain the preternatural way we knew to root for Kathy over Lina in Singin’ in the Rain, and why we firmly believe Rachel “deserves” to win over Darcy in Something Borrowed? We know what you look like. Her presence is required for a role grander than merely being opposition to the onscreen leading lady: She is an antagonist for viewers, too. We have been told, in large ways and small, that there’s a version of her – coiled and watchful – somewhere in our own lives, just waiting to impede our path to love.

The romantic-comedy bitch has been a staple and a shorthand for the roles women are allowed to occupy in society.

In recent years, the romantic-comedy bitch has morphed into something subtler, yet bolder. She has been more completely folded into the romantic comedy heroine, making for modern stories in which the friend and the foe are one and the same – see Trainwreck (2015) for the most recent and perfect example of this evolution. The romantic-comedy bitch has been a staple and a shorthand for the roles women are allowed to occupy in society, and also how we punish their transgressions when they veer from the path. The punishment we have meted out to these characters is for our edification, perhaps – a teaching moment that comes early and often. When we crush the romantic-comedy bitch, we are crushing the worst versions of ourselves, elevating us to the place where we are worthy of love. But maybe it’s time to stop using her as a punishment crutch – and just let the woman live.

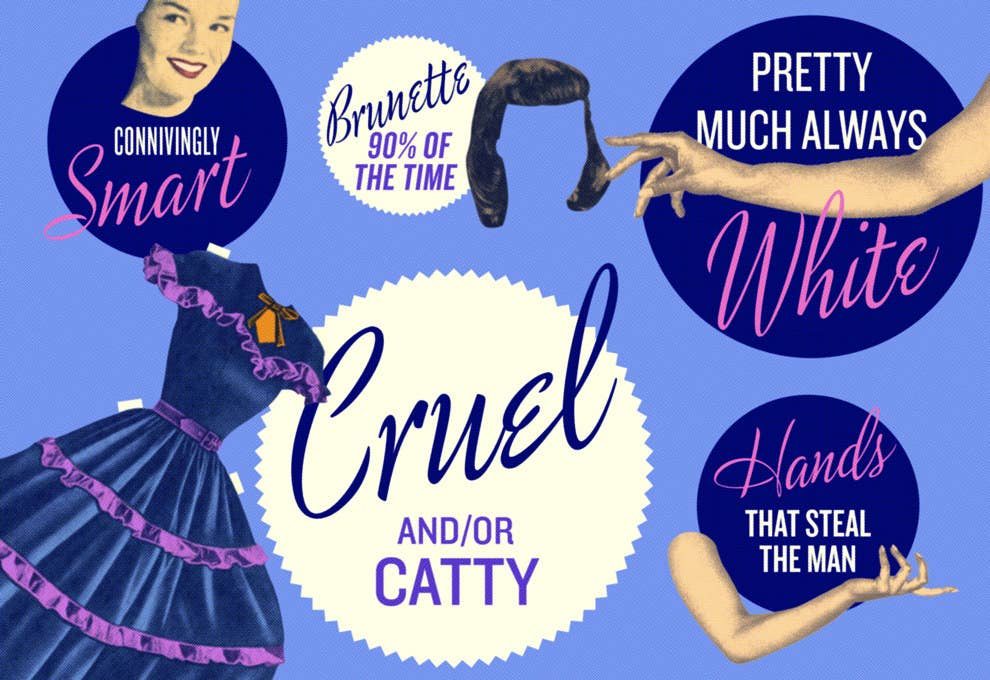

In 1976, Laurel Thatcher Ulrich wrote that “well-behaved women seldom make history.” I submit a less erudite construction of my own: Well-written romantic-comedy bitches live on forever. To be a memorable and familiar rom-com bitch, or RCB, there are key elements that need to be in place: The RCB is often hard – hard-nosed or hard-faced, it doesn’t matter which (see Selma Blair as Vivian in Legally Blonde). And though she may be not very bright (our protagonist is always smart, in her own way), she’s always calculating (see Jean Hagen as Lina Lamont in Singin’ in the Rain). Hers is the kind of smart that is cold and insufferable and unattractive to women (see Fiona in Four Weddings and a Funeral. Also, Selma Blair in anything). Where our heroine is a guileless, undercover but unassuming supermodel with a MacArthur Grant-level brain, the RCB has a conniving sort of smarts, and is perhaps cruel and/or catty (see Jean Hagen/Lina Lamont again!). She may be beautiful – and if she’s on the big screen, she likely will be – but that is not necessarily a requirement for the RCB. She is often white, and though that’s not a specific prerequisite, it sure appears that way, no? (See all of Hollywood… You get the picture.)

The alchemy of those traits is delicate, though, and you need a sturdy foundation to build it on. That the Bingley plot, first published in 1813, survives to this day is testament to its usefulness. At first glance, Caroline Bingley appears to be almost peripheral to the action in Pride and Prejudice: She is the youngest of the Bingley siblings, and her first appearance in the novel is in service of setting up her brother, Charles, the B-plot hero. Of the Bingley sisters, Austen writes, “They were in fact very fine ladies; not deficient in good humour when they were pleased, nor in the power of making themselves agreeable, when they chose it…” So far, so good. But then Austen deals the fatal blow that goes on to characterise the archetype for the next two centuries. “But [they were] proud and conceited.” Caroline’s sister Mrs Hurst is a bad egg, sure, but it’s Caroline who heads up a lineage that forms the blueprint for the character we recognise as the RCB.

Austen applies Miss Caroline Bingley judiciously in her novel. She appears early, and Austen immediately makes her an accessory to Darcy’s arrogance. (Men need to be arrogant in romantic comedies; it makes the “falling” part of falling in love more satisfying, I suppose.) A few pages later Caroline makes another cameo, this time to lightly mock our heroine Elizabeth’s manner and state of dishevelment when she visits Netherfield Park to check up on Jane. And while Austen benches her often throughout the novel, Caroline pops up whenever we need mild conflict, serving our drama needs by belittling elements of Elizabeth’s character or providing other Bennet-focused antagonism. These tactical deployments make for a lot of #impact. And we’ve been following the same script ever since.

When it comes to building an RCB, the only basic rule is that she is perceived to be a threat to the romantic well-being of our heroine.

When it comes to building a movie’s RCB, the only basic rule is that she is perceived to be a threat to the romantic well-being of our heroine. For all of her flitting around in Darcy’s orbit, Austen makes it clear that Miss Bingley doesn’t really stand a chance against Lizzie in Darcy’s affections. But Elizabeth doesn’t know that for sure, and from that tension, something beautiful is created. The template thereafter becomes a loose thing, and the screenwriter gets to wring a lot of pleasure from colouring her in. Perhaps this is why RCBs are often so much fun. As a formula, “boy meets girl” is pretty stale. But when you add in a loose cannon of an RCB, you can make magic happen in a few clean scenes.

In rom-coms, the “good” and “evil” dichotomy needs to be set up fast, and economically. For the limited airtime the greatest RCBs get, they manage to lodge themselves in our collective brain. Everyone who has seen Bridget Jones’s Diary recalls Lara-from-the-New -York-office’s line to Daniel (but pointedly meant for the ears of Bridget): “I thought you said she was thin..?” She achieves maximum bitch velocity in less than 10 seconds.

In Two Can Play That Game, Conny Spalding swings into view with a thick ponytail and a hot red suit, and fake-smiles her way through an embrace with the heroine. In While You Were Sleeping, Ashley Bartlett Bacon arrives in a blaze of impatient condescension as she eyes the doorman of her fiancé’s apartment building. She whips off her dark sunglasses and her first words are a sharply belittling “You’re new.” When she arrives at Peter’s hospital bed, she greets him with a cheerfully blunt “Scumbag!” If I’m going to have limited screen time, she seems to be the thinking, you better believe I’m going to leave my mark on the audience.

For love to succeed onscreen, it has to feel like a win. A strained long-distance relationship, for example, is a hurdle that can test a love affair, but is generally easily rectified. It’s far more gratifying for the audience if the obstacle to a successful relationship is shaped like a human woman – and more than that, a human woman who is set up to fail from the get-go. For a certain kind of romantic comedy, there is a pleasure in actively rooting against somebody. We want our heroine to ascend the stairs of love, but ideally she must trample somebody else underfoot as she does so. Think of the visceral thrill you get when you see Katharine (Sigourney Weaver) in that hospital bed in Working Girl, literally broken (it’s a leg, fractured while skiing, but we’ll take it). Or the scene where Trask fires her in front of everyone. The RCB exists as the Platonic Ideal of the love rival (never mind if she was never actually in contention for the love of the hero), but she is also just plainly the automatic enemy.

It is important, at this juncture, to note the types of RCBs we have come to know (note that she does not appear in every single romantic comedy, and she may even cross genre from time to time). There is the purest form of RCB, the Ol’ Bingley: unadulterated, unlikeable RCB. She is Lara-from-the-New-York-office, and she is fake best friend Lucy from 13 Going on 30, and she is Mia, the secretary in Love Actually who propositions the Alan Rickman character by letting her legs fall open after telling him their party venue is “full of dark corners, for doing dark deeds.”

Secondly, there is the the RCB you love to hate, the entertaining one who delivers tart lines archly, like Fiona in Four Weddings and a Funeral, or Parker Posey’s character in You’ve Got Mail. There’s a version of her in Emily in The Devil Wears Prada, and also in the Natasha Richardson character in Maid in Manhattan. A darker version of this RCB was to be found in Kathryn Merteuil (Sarah Michelle Gellar) in the darkly comic (sort of?) 1999 teen-love mess Cruel Intentions (you could spot her by her coke crucifix). These are the ones we remember almost fondly, like the school bully after a period of some years.

And because rules were made to be broken, there is a third kind of RCB, a hybrid creature that has become more common in recent years. This RCB is something of a two-for-one bargain: She is both heroine, aka the trampler of the RCB, and the RCB herself (#GetYouAGirlWhoCanDoBoth). For the origins of this particular breed, we go back even further, to William Shakespeare’s 16th-century Katherina, from The Taming of the Shrew. In the modern retellings Deliver Us From Eva (2003) and 10 Things I Hate About You (1999), Eva and Kat are their own antagonists, getting in their own way in the pursuit of true love. Further examples include Margaret in The Proposal (2009), Jules in My Best Friend’s Wedding (1997), Andie in How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days (2003), and Cher in Clueless (1995).

They are their own worst enemy (as all women are, right?), along with being the star of their own love stories. Hers is the bitchery we would want to emulate as the occasion demanded it, born of a modern woman’s real concerns: In The Proposal, Margaret is a little hard and unyielding, but wouldn’t you be too, if you were an orphan who’d made it to the top of the heap in a tough industry with rampant sexism? In My Best Friend’s Wedding, Jules is merely staking a claim to what she thought (erroneously, it turns out) was hers – a pact to marry her backup plan, aka Michael. Eva in Deliver Us From Eva raised her three sisters after their parents died, and has taken helicopter parenting to new heights. This version of the RCB might well be the one the modern audience relates to most readily, because she embodies the best and worst of us simultaneously, and somehow, thanks to the golden formula of romantic comedy, she always gets to win. We like her because we are desirous of her life. The RCB evolved, because we too have evolved.

So it’s important that this kind of RCB feels a little different: She can be a somewhat less ~problematic~ bitch than other strains of RCB, because she’s not just a plot device. In Trainwreck, Amy Townsend is mean and inconsiderate and very often charmless. But hey! She also reads as “authentic,” from strongly and regularly voicing her dislike of her sister’s domestic setup to not really challenging her father’s racist views because she loves him. Screenwriters get to ascribe the catchall “complexity” to a heroine’s less-than-great character flaws. “This is what an actual real woman acts like” is a solid defense, even when critics draw a big-picture image of how these representations, cumulatively, might ultimately be harmful to how we see women off the screen.

The RCB as a staple of the genre is already the source of some vexation, playing as it does into some fairly retrograde models of femininity. In an industry that has not historically treated its nonwhite members with parity, it’s no surprise that there is a relative dearth of romantic-comedy vehicles for actors of color. Consequently, it’s also no surprise that there are not as many nonwhite RCBs in the genre. As studios continue to catch up with receptive audiences, there are more chances to portray the aforementioned complexity female characters are finally being furnished with, and to do so while moving beyond the usual suspects.

If Trainwreck’s Amy is a perfect recent example of the difficult-but-ultimately-appealing romantic-comedy bitch lead, then it’s time to look at another from the same mould: Sara Melas from 2005’s Hitch. Sara is played by Cuban-American actor Eva Mendes, and is a flinty newspaper gossip columnist (the type who spots a story while she’s on holiday and rushes home to file copy). “What’s your name?” she asks the man hitting on her in a bar. “They call me Chip.” “Aw, you can’t get ‘em to stop?” she slings back immediately. It’s a great line, and Mendes delivers it wonderfully. The whole meet-cute in the bar is great, in fact: Hitch (Will Smith) arrives to “rescue” her from Chip, they match wits, they smile, they are attracted, and well pleased by the encounter, and then Hitch glides away with a perfect final flourish.

Sadly, that scene is seemingly the last attempt the script makes to move Sara into the realm of likability, or even real knowability. She comes across as hard rather than merely tough, and more than a little rigid. There comes a point in the movie where the viewer might ask, Why should I care about this virtual stranger? In fact, we root harder for the couple in the B-plot, Albert and Allegra (Kevin Smith and Amber Valletta), than for Hitch and Sara, and it’s not hard to decipher why.

Despite her being a co-lead, this is resolutely not Eva Mendes’s movie – in fact, in the first 30 minutes of the film, we see her in only three quick bursts – and the biggest consequence of playing third fiddle to Will Smith and Kevin James is that she is woefully underwritten. When you add race into the analysis of Sara’s character, a delicate intersectionality becomes apparent.

If we are finally cutting the RCB some slack, or at the very least, appreciating her as an icon worthy of cultural respect and affection, it matters what she looks like. What happens when the RCB isn’t white, in a culture in which we subconsciously but automatically assign undesirable traits to brown and black people? Particularly, as in the case of Hitch, when it’s a mainstream Hollywood movie in which two of the only visible people of colour in the main cast are leads? Is Mammy still Mammy if there is no Miss Scarlett to call on her? Race complicates an already fraught archetype: Sara Melas sidesteps any interesting route her character could’ve taken and is instead reduced to a sort of bad-tempered, ~fiery~ Latina.

Compare Sara to another nonwhite romantic comedy lead, Eva of Deliver Us From Eva. Eva (Gabrielle Union) is a difficult woman. She is a meddler, and a know-it-all, and not that pleasant with it (“I’m in damn good company – Martin Luther King was uncompromising! Nelson Mandela was uncompromising!”). The man who would tame the shrew is Ray (LL Cool J – don’t laugh) and he feels the full lash of her tongue from the moment they meet. And yet, by virtue of good writing, the charm of the performer, and – this is crucial – being situated in a movie in which she is visibly not a racial minority, it works. There’s more room to maneuver, and to flesh out the character with the details that make us care, and allow us to see her as a complete human being.

Context, like black life, matters.

Over the last 200-odd years, Miss Bingley has undergone a subtle transformation: The romantic-comedy bitch has transmuted into something that we carry within ourselves. The complex idea of internalising the enemy begs the question, if we are now also the bitch, and RCBs need to be trampled underfoot, how do we go about vanquishing ourselves? Our onscreen tastes may have evolved to encompass changing demographics and big societal changes, but we still bay for the blood of humiliation of some sort for the RCB, perhaps in an effort to try to remind ourselves to keep the “worst” parts of ourselves in check. And while a new crop of romantic comedies are largely trying to resist the impulse to pit women against other women, folding the RCB into the heroine only works up to a point, if it means we simply self-flagellate.

May I humbly suggest, for the good of all, that we let Miss Bingley – and all her many hybrid descendants – go. For every allegedly evolutionary leap the RCB has made, the bottom line is that she is ultimately just a very handy plot mechanism: problematic woman as chaos-bringer. And it is time to move beyond that. Let’s lose the bitch as plot device and push Hollywood to write complex female characters that, even in a romantic comedy, are looking beyond landing a man as the ultimate pursuit or screwing over women to get ahead. Let the RCB ride off into the sunset, secure in the knowledge that her work, while highly valued for 200 years, is done. In Working Girl, Tess (Melanie Griffith) literally puts on the clothes of Katharine, her own RCB, and in this costume manages to propel herself into the love and work life she's always wanted. It was a symbolic act; the capacity for a successful life was in her all along. And it’s the same for so many of us (outside of the institutional barriers that have been built up over generations, lol).

So it’s time to beat that gong even more urgently: Retire the RCB. Retire humiliating women for the alleged benefit of other women. Dare to imagine a world in which the bitch is not back, but kicking off those pinching Louboutins with wild abandon, sipping from a cocktail glass, umbrella garnish discarded, living a version of Her Best Life™.

Want more of the best in cultural criticism, literary arts, and personal essays? Sign up for BuzzFeed READER’s newsletter!

If you can't see the signup box above, just go here to sign up!