The everyday and the existential: how Clinton and Trump challenge transatlantic relations

Summary

- The transatlantic relationship is likely to face difficult challenges whatever the result of the US election.

- If Trump wins he will launch a revolutionary presidency — pulling back from NATO and other security guarantees, undermining key parts of the global free trade regime and building closer relations with strong-man leaders than allies.

- Even if Hillary is elected the transatlantic relationship could still face difficult albeit more everyday challenges. Her poor relations with Moscow, exacerbated by gender issues, could threaten transatlantic unity on Russia.

- Europe would be foolish not to learn lessons from the experience of Trump’s candidacy. Trump represents only an extreme version of a growing feeling in the United States that, in a time of relative decline, the country is getting a raw deal from its allies.

- The EU should not be complacent in assuming that the transatlantic relationship will continue as it is and should begin to take more responsibility for its own defence and build resilience against a potentially more self-interested US.

Introduction

It was bad luck that President Donald Trump’s first visit to Europe was to Sicily. Trump generally didn’t travel overseas much. But he wanted to attend the G8 meeting there ― largely because he had arranged for his good friend Russian President Vladimir Putin to rejoin the club. The only problem was that Trump’s understanding of Sicily came almost entirely from his unswerving devotion to the Godfather movies.

Accordingly, his speech to the assembled leaders of the major democracies noted that, henceforth, European and Asian security would be run on a strict Mafia protection model. “Nice little country you have here”, he joked to a stone-faced Italian prime minister, “shame if something happened to it”. Even before the formal “offer that Europeans couldn’t refuse” arrived later that summer, the effect on the United States’ relations with its European allies was nothing short of catastrophic.

This is a piece of fiction, or at least a premature description of reality. But it highlights the type of challenge that the 2016 US presidential election poses for Europeans.

Trump particularly represents a new challenge. Transatlantic relations have long been predictable, even boring. Even their dysfunctions and disputes are ritualised and repetitive ― something that makes life difficult for analysts and journalists looking for new or exciting material. But it has served the interests of the transatlantic partners fairly well. In geopolitics, repetitive, boring disputes at summit meetings are in fact an amazing and historically rare achievement.

For all of the complaints on both sides of the Atlantic, the alliance has functioned quite effectively in recent years. From a US perspective, European allies, individually, and through multilateral forums such as NATO and the EU, have remained the partners of first choice. European allies are America’s key partners in every major foreign policy endeavour, particularly in military operations. For Europe, the alliance has served to keep Americans interested and involved in European issues, even as the Middle East continues to burn and Asia grows in geopolitical weight and danger.

For these reasons, the alliance remains important to policymakers on both sides of the Atlantic. But now, for the first time in generations, the very concept of “alliance” is being called into question by a US presidential candidate. The Republican nominee, Donald Trump, has been clear that he views the alliance in instrumentalist terms. Unless the alliance is radically reshaped, Trump claims that America will simply walk away from Europe, leaving it to deal with its problems on its own.

The Democratic nominee, Hillary Clinton, presents a much more familiar challenge to the alliance, but her approach to Russia, as well as the growing American demand for Europeans to take greater responsibility for their own security, means European leaders will still have to take some very difficult decisions.

What would a Trump or Clinton presidency mean for Europe, and how should Europeans respond to the potential ― and in one case existential ― challenges that these candidates will present?

Trump’s existential challenge

One needs to be wary of predicting what Trump would do as president. He has avoided making specific pledges throughout his campaign, and dodged external pressure to provide them. Trump has been mostly focused on domestic issues and immigration during the campaign. On foreign policy, he has embraced a level of inconsistency that celebrates the idea that his policy pronouncements are beyond the dictates of logic. So with one breath he can declare a profound disinterest in using force abroad, but with the next propose to “bomb the shit” out of ISIS-controlled oil fields in Iraq and Syria, surround them with a “ring” of American troops, and take the oil.

This lack of consistency has led many to assume that it doesn’t really matter what he says on the campaign trail. A forthcoming ECFR survey of European views of the transatlantic relationship demonstrates the widespread belief in European governments that either the American system of checks and balances will constrain Trump from implementing his more radical proposals, or that he doesn’t mean it when says, for example, that he may withdraw from NATO.

This is a dangerously complacent notion. American presidents have long had enormous latitude on foreign policy. In the years following the 9/11 terror attacks, Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama have further centralised foreign policy decision-making in the White House. The Congress, divided and inert, has barely even protested, and indeed largely avoided taking any responsibility for foreign policy.

Judging by the reaction of Republican congressional leaders to Trump’s campaign rhetoric, there is little reason to believe they would behave differently under his leadership. President Trump would therefore take over a well-honed and independent executive machinery for conducting foreign policy ― one that includes a virtually unlimited capacity and authority to assassinate people in much of the world.

And while Trump often contradicts himself, as Thomas Wright of the Brookings Institution has demonstrated, a core consistency has animated his understanding of foreign policy for decades. There are three pillars of his foreign policy thinking from which he has never wavered. The first is the idea that America is getting a bad deal from its allies; the second is that the American approach to free trade has impoverished American workers and weakened the United States; and the third is that as a strong leader he can secure better deals with authoritarian strongmen than by working cooperatively with European allies.

America’s crappy allies

Trump has consistently claimed that America is getting a raw deal from its allies and the global order in general. In 1987, he spent nearly $100,000 of his own money to take out a full-page ad in the New York Times just to make this point. America, the letter declared, has been stuck with the bill for global security for generations and gotten precious little in return. The US secures Europe and Japan, yet is forced to pay for the privilege. It liberated Kuwait and Iraq, yet gave the oil wealth there to others who stood by and watched American soldiers die in their defence. The 1951 US–Japan security treaty is, in Trump’s view, the perfect example of this type of raw deal because it obligates the United States to defend Japan, but does not obligate Japan to defend the United States.

This sense of a bad bargain often seems to make Trump angrier at America’s allies than at its enemies. America’s enemies strike hard deals, but at least you know where you stand with them. So he can imagine that Russian President Vladimir Putin is someone he “would get along with very well”. But America’s allies are like poor relatives, who play on your sympathies to borrow money and then spend all day frolicking in your swimming pool. So when it comes to German Chancellor Angela Merkel, Obama’s most important interlocutor in Europe, all Trump sees is someone who is “sitting back” and “accepting all the oil and gas that they can get from Russia”, while the United States is “leading on Ukraine”.

Trump is set on securing a better deal from US allies. A better deal, in Trump’s version of the transatlantic alliance, involves European allies like Germany paying for the privilege of American protection. If they fail to meet their “obligations”, they will not be defended. More than this, Trump’s view is that allies should not need American protection at all. He will expect Europe to shoulder the burden for dealing with conflicts that are primarily European problems, such as the war in Ukraine and the refugee crisis.

Bad trade deals

The second pillar of Trump’s foreign policy is that free trade deals have hurt America. Trump’s views on trade can also be traced back to the 1980s and the debates over US-Japanese trade. In his view, American elites, in an effort to woo allies away from the Soviet Union, sacrificed the interests of the American economy and American workers to foreign interests. With the Cold War long over, this habit of mind is no longer relevant, if it ever was, and the United States can now pursue better trade and investment deals that put its own economic interests ahead of the global ambitions of its cosmopolitan elites. According to Trump, “Americanism, not globalism, will be our credo”.

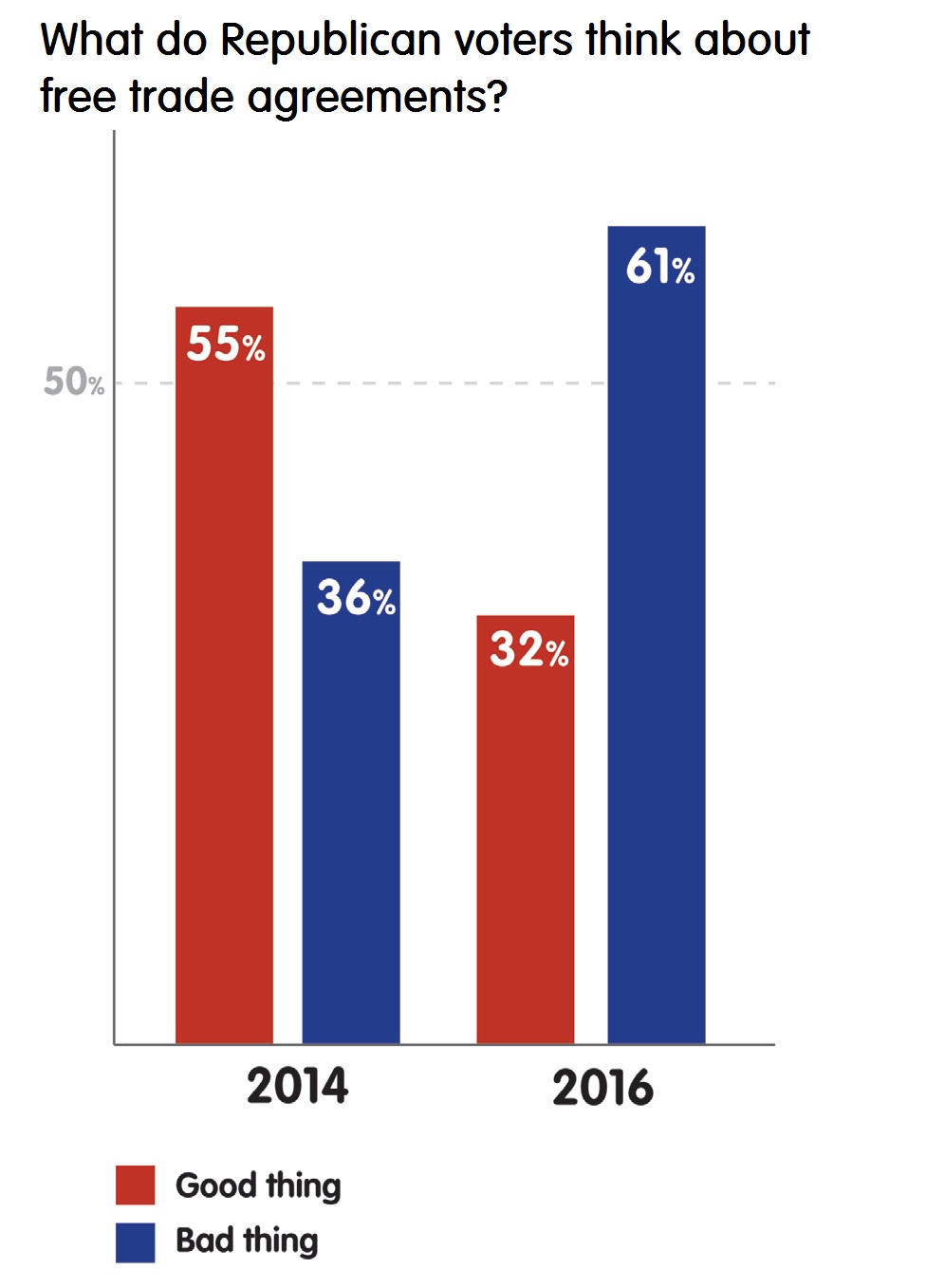

Already Trump’s views on trade have had an impact on Republican voters’ traditional support for free trade. In a dramatic turnaround, 61 percent of Republican voters now believe that free trade is a bad thing, as compared to only 36 percent in 2014.

Trump has consequently pledged to overhaul America’s trade policy and pull the United States out of a wide range of “unacceptable” trade deals, including NAFTA, the (still unratified) Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), and even the World Trade Organization. The prospect of a Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) would die the day he entered office.

It is important to note, however, that Trump does not believe that trade is inherently bad for the American economy. Rather, he believes that the practice of negotiating multinational trade deals has disadvantaged America’s economy. “No longer will we enter into these massive deals, with many countries, that are thousands of pages long, and which no one from our country even reads or understands … Instead, I will make individual deals with individual countries.” In so doing, he seems to believe that, in bilateral negotiations, he could leverage the size of the American market and his own negotiating skills to obtain a better deal for the US.

The advantage of the strongman

As Wright documents, Trump’s fascination with strong, authoritarian leaders is also not a new development or unique to his presidential run. After a 1990 visit to Moscow, Trump criticised Mikhail Gorbachev’s lack of a firm hand in responding to challenges to Soviet rule in Eastern Europe. He contrasted that supposed weakness with the Chinese’s leadership strong response to the 1989 protests in Tiananmen Square. “They were vicious, they were horrible, but they put it down with strength. That shows you the power of strength.”

Trump’s praise of strength and of authoritarian strongmen has been a common refrain during his election campaign. He has variously praised former Iraqi President Saddam Hussein, North Korean dictator Kim Jong-Un, Syria’s murderous President Bashar al-Assad, and the late Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi. Most prominently, Trump has engaged in something of a bromance with Putin, praising his decisiveness and touting the Russian president’s alleged comment that Trump is “brilliant”.

Trump’s admiration for strong leaders reflects more than just a personal preference. It illustrates his sense that strong individuals “win” in history. Systems that prevent strong leaders from emerging, either because they diffuse power and decision-making too much or because they don’t value the traits of strength, create weak leaders and therefore weak nations. The European Union, which is not noted for its strong leadership, is therefore doomed in Trump’s view: “I think the EU is going to break up,” he said in the days after the Brexit vote, “… the people are fed up.”

Trump’s view reflects a widely noted disadvantage of democracies ― though it fails to account for the fact that the strongest and richest countries on Earth are democracies. Regardless, Trump’s faith in strong leadership means he believes that democracies cannot be strong unless they produce an assertive leader. Only such leaders can cut through the morass of competing interest groups and strongly assert the national interest.

Why Trump’s challenge is new

Trump’s core worldview presents a serious challenge to the transatlantic alliance. Of course, a desire for more equitable burden-sharing has been present in American foreign policy for decades. President Obama’s pivot to Asia reflected the notion that Europe was not capable of dealing with its own problems and that the excessive American military presence in Europe had led Europeans to neglect their own forces.

US Secretary of Defense Bob Gates ended his tenure in office in 2011 with a blistering attack on European irresponsibility in defence:

“The blunt reality is that there will be dwindling appetite and patience in the US Congress, and in the American body politic writ large, to expend increasingly precious funds on behalf of nations that are apparently unwilling to devote the necessary resources […] to be serious and capable partners in their own defence.” To this he added that there is a “real possibility for a dim, if not dismal, future for the transatlantic alliance.”

But comparing Obama and Trump shows what is new about the Republican nominee. Previous US efforts to equalise the security burden, including Obama’s, have always been based on the notion that America’s best partners are democracies, that its own prosperity is derived from a broad global system of trade and investment, and that Europe’s security must be protected — by Europe if possible, and by the United States if necessary. Previous post-war American presidents have explicitly looked for a more equitable partnership with Europe, but they believed that Europe’s security and prosperity were a core interest of the United States and have therefore been wary of abandoning Europe and leaving it to its own devices.

This bargaining approach, in which America’s commitment to Europe is never questioned, has weakened US leverage. Implicit in the current approach is the assumption that the United States will take up whatever slack Europe leaves behind. And so Europeans end up free-riding on American security guarantees. However, the current model also reflects a historically sound belief that the United States does have a stake in European conflicts, and cannot ultimately stand aside from them.

Trump, in contrast, believes in walls and in oceans. In his view, America can and should stand aside from problems in other regions. For example, Trump doesn’t believe that the US should offer assistance on the European refugee crisis, because “we have our own problems”. Unlike any US president since Harry S. Truman, Trump doesn’t believe that America has special relationships with countries because they are democracies. After all, he sees democratic nations as inherently weak. Instead of being lambasted by weak democratic allies, he believes he can formulate individual deals with authoritarian leaders that can better support American economic and security interests.

Because Trump could walk away from existing allies, this type of thinking considerably strengthens his bargaining power with Europe and other allies. But in the process it might destroy the transatlantic partnership that has made both sides of the Atlantic so secure and prosperous.

Clinton’s everyday challenge

As president, Hillary Clinton might lack some of Trump’s leverage, but she would still be seeking to get Europeans to contribute as much as possible to their own security and to US efforts at promoting stability elsewhere.

From a European perspective, this makes Clinton a far more “normal” and comprehensible presidential candidate — and not just compared to Trump. She has been a presence in national politics for more than 25 years and has a long history in politics ― as first lady, senator, and secretary of state. Her foreign policy views place her firmly at the centre of the American foreign policy spectrum and firmly within the long-held consensus on the transatlantic alliance.

Indeed, Clinton is perhaps more normal than is appropriate given the national mood. The extensive support for Trump and also for Senator Bernie Sanders, in the Democratic primary, indicates that much of the electorate is disillusioned with establishment figures. There is a sense among voters that both the Bush and Obama foreign policies got the United States too involved in the world and failed to put America first.

Be that as it may, it is surpassingly simple to describe Clinton’s basic approach to the transatlantic alliance. Like every president since 1945, she will rely on the alliance as a cornerstone of her foreign policy. And like every president for nearly that long, she will, within the confines of that approach, seek to shift some of the burdens for global and particularly regional European security to the larger powers of Europe. Like Obama, she will seek to reallocate some of the resources spent on European security to areas of greater urgency, particularly East Asia.

This core approach is too familiar to merit a very detailed explanation. Instead, the paper will focus on three less commonly discussed, but no less important, aspects of her approach to foreign policy and transatlantic relations that will have an impact on Europe. The first is the essential continuity in foreign policy that would result from a Clinton presidency, including on the use of military force. The second is the role of gender in her approach to foreign policy. And the third is her approach to Russia, which stands out as an exception to the basic rule of foreign policy continuity between her and Obama.

The essential continuity between Obama and Clinton

As is normal for someone running to succeed a president of her own party, Clinton has made an effort during the campaign to disassociate herself from the less popular aspects of Obama’s foreign policy. As a Democrat, representing a party often linked with anti-militarism, and as the first female major party candidate for president, she has been particularly careful to project an image of strength and a willingness to use force. This effort, as well as her past record supporting US military interventions, including the war in Iraq, have led to a widespread view that she would resort to force much more often than Obama, particularly in Syria.

But this view hides an essential continuity in how she and Obama approach foreign policy problems. It also underestimates just how often Obama has used force. He has been at war every single day of his two-term presidency, the only American president to achieve that dubious distinction. He has taken military action in seven Muslim-majority countries, and dramatically expanded the use of drones and Special Forces. Such a view also underestimates just how important Clinton herself was, as secretary of state, in helping to shape Obama’s approach to foreign policy.

Like Obama, Clinton has often favoured the use of force. As first lady in the 1990s, she supported US intervention in the former Yugoslavia, and, as a senator, she voted for the war in Iraq in 2003. In 2009, she supported the troop surge in Afghanistan. As secretary of state, she advocated for military intervention in Libya in 2011, as well as for forceful measures in Syria. And in her current presidential campaign, many of her foreign policy advisers are prominent advocates of increased use of the military, particularly in Syria.

But it is unlikely that President Hillary Clinton would be the uber-hawk that so many expect. This is, in part, because her record as a policymaker is more nuanced than is often appreciated. She has just as often pushed for diplomatic solutions as military ones.

As secretary of state, Clinton frequently complained about the militarisation of US foreign policy and touted the virtues of “smart power” (the idea that all types of national power are needed to solve foreign policy problems) and diplomacy in tackling the nation’s most serious national security challenges. She started secret negotiations with Iran in 2012 that ultimately led to the momentous Iran nuclear deal. She has similarly supported Obama’s rapprochement with Cuba. She also supported and implemented the reset with Russia that began in 2009. When China started becoming aggressive in the South China Sea, she didn’t reach for military tools, but instead pushed forward a regional diplomatic approach that stood in stark contrast to Beijing’s military aggression.

But perhaps more importantly than her record, Clinton will be inclined to look towards diplomacy because, as president, she will find that the use of force abroad will offer precious few opportunities for making a difference, and will come at a considerable political cost at home.

In Syria, the idea of risking US boots on the ground or war with the Russians to support an opposition that consists largely of Islamist extremists is not likely to appeal to her any more than it has to Obama. When it comes to fighting ISIS, Clinton also seems comfortable with Obama’s template for the use of military force: the limited use of armed drones, special operations forces, air strikes, efforts to build local capacity for ground operations, and stabilisation duties.

Changing these policies would be politically risky. As recent presidents have learned, military intervention abroad can weaken political support at home. Despite the headlines of global disorder, neither the American public nor the Congress have much appetite for a more active military policy.

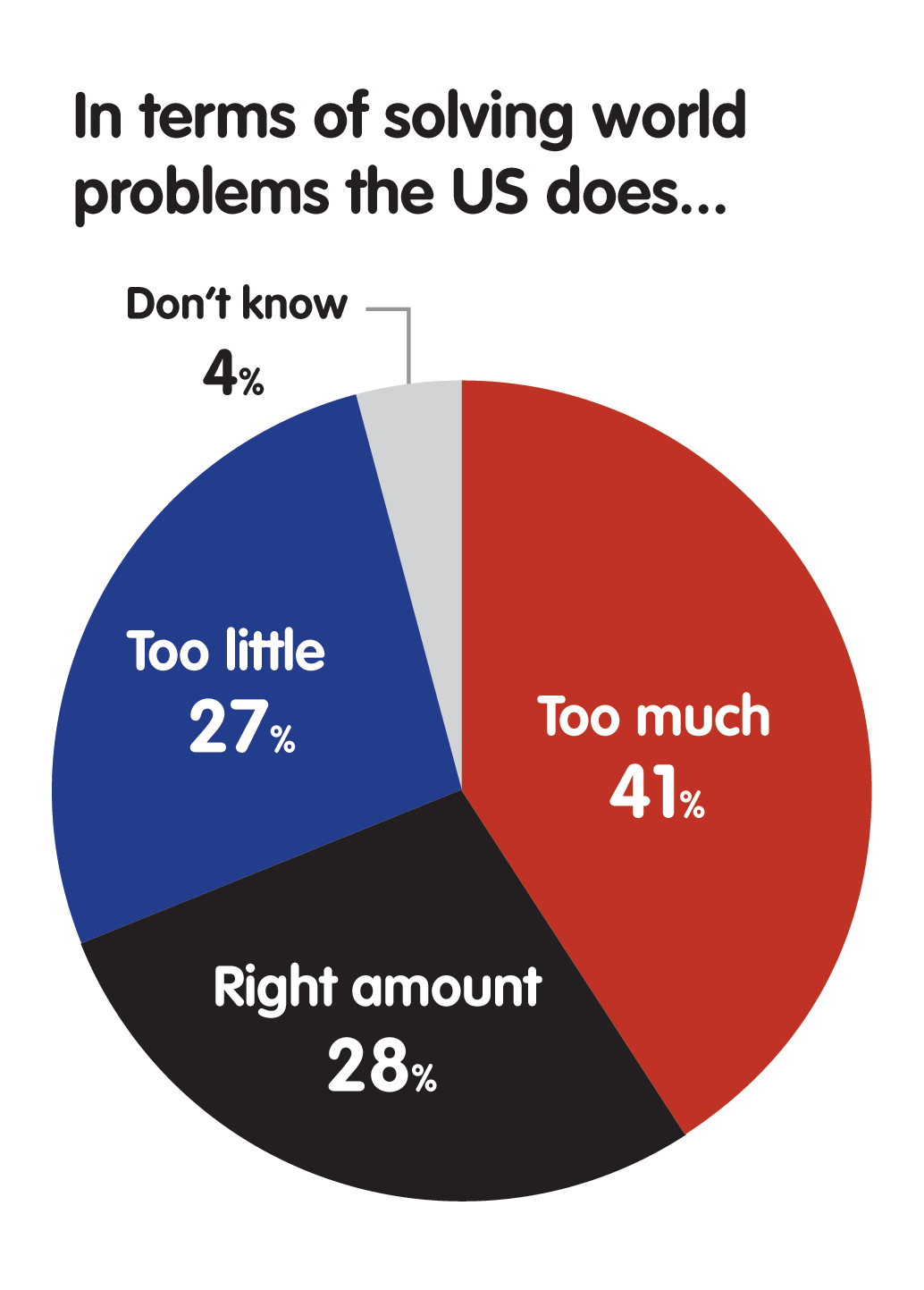

This became clear on the campaign trail in both the Democratic and Republican primaries, when hawkishness emerged as a political liability that both Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump profited from. A recent survey from Pew Research Center, for example, found that 57 percent of Americans surveyed want the US to deal with its own problems, while letting other countries get along as best they can. Only 27 percent of respondents felt that the United States is doing too little to solve world problems.

Clinton has always reserved her greatest passion and vision for domestic issues. She wants to make her mark in domestic policy and she will likely reserve her political capital to make the deals and compromises that will be necessary to advance her domestic policy agenda. Like many presidents before her, Clinton may find that she needs to turn to foreign policy to make her mark later in her presidency. But she will begin as a domestic policy president, fighting difficult battles for priorities such as immigration reform, better funding for infrastructure, and paid family leave.

Like her predecessor, Clinton will not run the risk of eroding her political standing unless she is convinced that there is a strong case for how any intervention will both improve the situation on the ground and meet with the approval of the American public. In the next four years, such cases will be few and far between.

A gendered foreign policy

Clinton’s approach to gender will also have an important impact on her foreign policy. When Obama became the first African-American president, he seemed very determined not to rule as an African-American. He took very few opportunities to highlight his race and did not give any particular priorities to issues of race in his policy agenda. His message seemed to be: “I am not a black president. I am a president who happens to be black.” In so doing, he likely reduced, although certainly did not eliminate, a racist backlash to his presidency.

For better or for worse, Clinton seems determined to take a different approach. In her current campaign, she has been much more willing than in 2008 to speak about her gender and about the historic nature of her candidacy. She has implied in various ways that she intends to be a female president in every sense, most prominently through her intention to ensure that half of her cabinet is female. This would almost certainly include the first ever female secretary of defence.

This all seems a natural fit. Clinton has been working for women’s equality and talking about women’s inclusion her whole life. Her first speech on the global stage was her address on women’s rights at the 1995 UN World Conference on Women in Beijing, in which she declared that “human rights are women’s rights, and women’s rights are human rights”. On leaving the State Department, she assembled a group of long-time female aides and told them that she wanted to devote herself to issues affecting women and girls in preparation for another presidential run. The New York Times, based on interviews with her close confidantes, calls the issue of women’s rights “the central cause of her career”.

Consistent with much feminist theory, Clinton seems to believe that women bring a unique and valuable perspective to decision-making and peacemaking that men simply do not possess. Women think more holistically, with greater attention to broad issues of social justice and economic development that men give short shrift. Their substantial presence in decision-making roles is essential for finding durable solutions to almost any social problem. Attention to gender equity is therefore necessary to achieve social stability.

As she said in 2011, “[f]rom Northern Ireland to Liberia to Nepal and many places in between, we have seen that when women participate in peace processes, they focus discussion on issues like human rights, justice, national reconciliation, and economic renewal that are critical to making peace, but often are overlooked in formal negotiations. They build coalitions across ethnic and sectarian lines, and they speak up for other marginalised groups. They act as mediators and help to foster compromise.”

It is unclear what this gendered concept of peace and reconciliation means for Clinton’s foreign policy. But this type of worldview does imply that she will only seek to build durable solutions or alliances with countries that allow women to be well represented in society and government.

Clinton’s Russia problem

Perhaps the least understood aspect of Clinton’s foreign policy is her approach to Russia. Critics frequently cite the 2009 reset as evidence that Clinton is soft on Russia. But in fact, Clinton’s experience as secretary of state deeply soured her view of the Russian regime. By 2011, she had accused the Russian regime of rigging the elections to the Russian parliament, and a year later harshly rebuked Putin for resuming the Russian presidency in 2012.

In the case of Syria, she was incensed at the assistance Russia provided to the Assad regime. In one speech in June 2012, she revealed that Russians were shipping attack helicopters to Syria and called out Russian claims that they were not being used in the civil war there as “patently untrue”. She has since compared the Russian annexation of Crimea to Adolf Hitler’s invasions of then Czechoslovakia and Poland in the 1930s, a statement perfectly pitched to anger a Russian leadership that sees the defeat of Nazism as Russia’s defining struggle.

Ironically, one reason for Clinton’s distrust of Russia is that the country’s decision-makers also have a gendered perspective on foreign policy. But that perspective is nearly the polar opposite of Clinton’s. The Russians maintain that women have no place in such discussions, and there are very few women in the upper echelons of the Russian foreign and security policy apparatus. Russia’s policy stance, as presented by its often-shirtless president, seems the epitome of a macho foreign policy.

As secretary of state, Clinton had a very bad relationship with her Russian counterparts. The delegations of men they brought to meetings with her and her team often seemed more intent on humiliating or flustering her than on achieving any particular policy outcome. According to Politico, Russian officials referred to her with both derision and respect as a “lady with balls”. After Clinton criticised the December 2011 elections, Putin personally accused her of fomenting protests against his rule and remains angry with her to this day over those events.

Even if Putin’s anger against Clinton is motivated by more than just gender, treating female counterparts with disdain is clearly part of Russia’s diplomatic playbook. People who worked with Condoleezza Rice when she was secretary of state suggest that she received similar treatment, despite being a Russia specialist and speaking Russian. And Putin’s ill treatment of Angela Merkel, including trying to play on her fear of dogs, is well known. Yet Clinton’s successor at the State Department, John Kerry, does not seem to have had these types of problems with the Russians, and has even bonded with his Russian counterpart, Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, over late-night dinners.

After Russia’s apparent effort to use underhand tactics, including hacking the Democratic National Committee, to support Trump in the presidential election, Putin and Clinton now apparently see each other as personal enemies that have actively tried to sabotage each other’s rule.

All of this means that under Clinton the US–Russia relationship is unlikely to improve. While many in Europe, and particularly in eastern parts of the European Union, may welcome a more confrontational Russia policy from the US, this is not necessarily good news for transatlantic relations.

The essence of the Obama administration’s approach to Russia since the invasion of Ukraine has been to maintain close alignment with the German position. Together, the Americans and the Germans have been at the centre of this debate and able to maintain unity among a diverse set of opinions within Europe about what the right approach to Russia should be. If the Germans and the Americans fail to reach future agreements on Russia and that centre ceases to hold, transatlantic unity will break down and the Western approach to Russia will devolve into confusion.

Challenges on both sides

Trump’s view of allies and trade represents an existential threat to the transatlantic alliance. That threat comes less from the inconsistent policy positions he has taken in the campaigns than from some of his core beliefs that stretch back decades. His views on allies, on trade, and on authoritarian leaders are fundamentally at odds with the decades-old principles of transatlantic relations. His volatile temperament and his tendency to ridicule allies means that he would bring a new and damaging tone to transatlantic diplomacy.

Overall, it would be the height of folly to assume that winning the presidency would change Trump’s core beliefs or finally subdue his ego.

Of course, Trump may not be president in 2017 and the transatlantic alliance would likely endure a Clinton presidency in something close to its current form. Under Clinton, the European everyday challenge will be, as it has long been, to maintain the American commitment to Europe without being overwhelmed by it. If Clinton is elected, there will be a temptation to assume that business can continue as usual. The alliance might even become boring again.

But such a return to the alliance’s boring predictability would be an illusion. The resonance of Trump’s “America First” message derives in part from the blessings of America’s geography and its historical myth of self-reliance. Trump can credibly say such things because the United States has options, in the short-term anyway, to insulate itself from the troubles of the world and even to reduce its economic reliance on global trade.

The EU has no such option — its geography means that it cannot insulate itself from the troubles of Eastern Europe or the Middle East for long; its economic structure means that it has an even greater interest in an effective global trading system than the United States. This fundamental distinction in the situations of the United States and the member states of the European Union means that there is a limit to the extent that Europe can rely on the United States for its security and prosperity.

Many of the member states of the European Union are becoming more introverted at the very moment that the security threats on Europe’s southern and eastern borders are growing worse. This is possible because, as ECFR’s surveys suggest, many governments in Europe still believe they can count on the United States to secure their core interests. Many privately indicate that they expect a Clinton presidency, particularly given her attitude towards Russia and her supposed hawkishness, to usher in a new phase of American leadership and commitment to Europe’s neighbourhood.

But even in the event of a Clinton presidency, Europe would be foolish not to learn lessons from the experience of Trump’s candidacy. Trump represents only an extreme version of a growing feeling in the United States that, in a time of relative decline, the country is getting a raw deal from its allies. The partnership cannot persist along the current lines for too much longer. The promise of future elections fought along Trumpian lines means that America will likely become more self-centred and less predictable as an international partner, no matter who is president.

Given the current direction of US politics, Europeans would be wise to take more proactive measures to visibly increase the burdens they bear within the alliance and their capacity for independent and cooperative action under the next US president — no matter who he or she is.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.