Fear of a College-Educated Barista

Is there really a Millennial underemployment crisis? Yes, but only among liberal-arts majors.

Since the Great Recession, a powerful and occasionally terrifying narrative about the state of recent college graduates has emerged: Many young, educated 20-somethings are languishing in the purgatory of unpaid internships. Those who have managed to find jobs earn wages whose meagerness stands in stark contrast to their student debt. Even now, seven years after the Great Recession, about half of young college graduates between the ages of 22 and 27 are said to be “underemployed”—working in a job that hasn’t historically required a college degree—including, most prototypically, that infamous caricature, the College-Educated Barista.

For many years, this crisis of overeducated latte artists seemed quite real, according to research by Jaison Abel and Richard Deitz, two economists from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. But now, armed with new data and more perspective, Abel and Deitz suggest a more subtle narrative. “The popular image of the college-educated barista … is not an accurate portrayal of the typical underemployed recent college graduate,” they write. Instead, they find that more young college graduates are now finding good jobs in their twenties. Finally, youth underemployment, like youth unemployment, is in decline.

This happy news comes with an important asterisk. A large chasm has opened between the fates of young liberal-arts majors and their peers in STEM (science, tech, engineering, and math) fields. The former are struggling to find work that pays, at least before their late twenties. The latter are mostly finding lucrative work after they graduate.

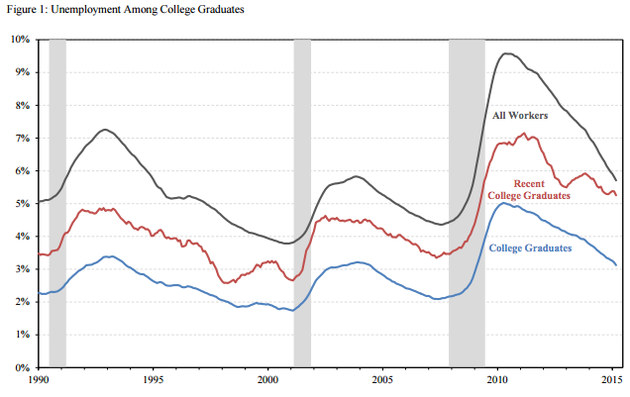

The story of underemployment among 20-somethings is one with several major implications for the value of college for young people today and the state of the U.S. economy. Since 2010, the labor market has added millions of jobs, and wages have increased for just about every cohort and demographic. But young college grads have faced several unexpected hiccups. While joblessness for the broader economy has fallen steadily in the last few years, the unemployment rate for recent college grads has been a much more jittery decline (see the red line below). Underemployment for recent college graduates is still higher today than it was in 2010 (or any other time in the 21st century).

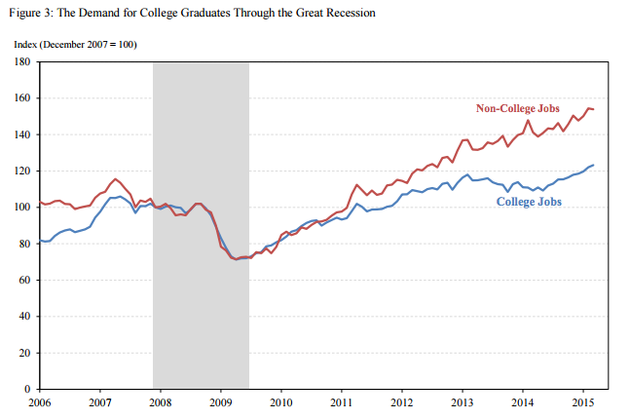

Meanwhile, something deeper seems to have changed. In the labor market for young college grads, non-college jobs have proliferated faster than jobs that have historically required a college degree.

Which young people are going into these less skilled, lower-paid jobs? Humanities majors, it seems. Liberal-arts majors “are two to three times more likely to be underemployed than those with engineering or nursing majors,” the authors found.

Indeed, the gap between humanities and STEM students is striking. Underemployment afflicts more than 50 percent of majors in the performing arts, anthropology, art history, history, communications, political science, sociology, philosophy, psychology, and international affairs.

But the undergraduate majors that promise the best shot at a high-paying job all have one word in common: engineering. Civil-, mechanical-, aerospace-, and industrial-engineering majors all have extremely low underemployment percentage and they are the least likely of all majors to land their degree-holders in a low-paying, low-skilled service sector job. “Our work does suggest that certain skills have a higher demand relative to supply than others—such as those majors related to the STEM fields and healthcare,” the authors write.

The finding raises several questions that don’t have obvious answers. Is the demand for young liberal-arts students flatlining? Perhaps. Are higher achieving students choosing STEM majors, so that their superior post-graduation jobs are more of a reflection of their innate talent rather than the power of the STEM major itself? Sure, it’s possible that worse students are clustering in a handful of humanities majors. Has the growth of college graduates from community colleges and for-profit schools diluted the overall quality of the recent college grads? That might explain some of these trends, as well.

For the last few decades, the value of a college degree has been economic and social dogma. College graduates, particularly from four-year schools, are more likely to work, more likely to earn higher wages, more likely to marry, and more likely to produce high-achieving children who complete high school and college. The fact of elevated underemployment for liberal-arts students doesn’t quite mitigate any of this. After all, the labor force is chaotic, and trying out a bunch of different jobs in one’s twenties is not only a reasonable way to spend the decade, but also there is evidence that it improves one’s odds of finding the right vocational match later on.

Thousands of college students will choose a major this year. Only a small percentage are likely to fully appreciate the immediately diverging paths of young sociology majors and nursing majors. If their aim is specifically to maximize their odds of lucrative post-graduation employment, the choice is easy: pick a major that ends in the word “engineering.” But there exists no study proving that a sociology major ruins lives. A career is a lifelong project, and underemployment, even for liberal-arts students, appears to be a temporary condition.