Drew Brees Has A Dream He’d Like To Sell You

With the Saints QB leading the way, AdvoCare is using its sports ties to build a nutrition empire. But is the company really pushing false hope?

ne weekend in early 2013, thousands of people trekked to the Fort Worth Convention Center in Texas, gathering to celebrate a company that promised to liberate them from the drudgery of their 9-to-5 lives. They cheered through countless inspirational speeches, pounding energy drinks and pumping their fists as higher-ranking members spoke about how they had turned their lives around with the help of AdvoCare, which is short for Advocates Who Care.

For three days, teams of AdvoCare members in matching T-shirts swarmed the concourse, taking photos with the company mascot (a generic superhero) and buying armloads of AdvoCare gear. There were raucous musical performances, as well as appearances by the Dallas Cowboys cheerleaders and former President George W. Bush. On Sunday, the organizers held a church service featuring Christian singer Michael W. Smith. The event was called Success School, but it didn't feel like an educational seminar, according to members who were there. It felt like a revival.

The weekend's biggest applause was reserved for AdvoCare's national spokesman: Drew Brees. When the quarterback emerged, the audience -- composed largely of new members -- screamed, roiling with the fervor of the recently converted. As electronic music thumped and images of spinning trophies flashed on a pair of giant screens, Brees, wearing a plaid suit jacket and an AdvoCare medal, strode toward the stage, high-fiving strangers. A regiment of his fellow endorsers, including Cowboys tight end Jason Witten, trailed him. Brees tossed a couple of tiny footballs into the crowd and beamed, covering his eyes as he scanned the crowd.

"You should all be excited," he said. "Because of you, we're gonna make AdvoCare a household name!"

The quarterback wasn't wrong. Today, the company boasts an army of 640,000 salespeople, up from 97,000 in 2010. These independent distributors sell energy drinks, shakes and supplements directly to consumers. But AdvoCare is pitching more than nutritional products. It's also offering people a pathway to financial freedom -- the opportunity to "design their own lives" by selling those products and to earn even more money by recruiting others to join the fold. This business model, called multilevel marketing, helped the company generate $719 million in net revenue last year.

As AdvoCare has grown, it has signed dozens of high-profile athletes as endorsers, including NFL QBs Andy Dalton, Philip Rivers and Alex Smith, MLB pitcher Doug Fister and CrossFit champion Rich Froning. But no spokesman matters more -- to the company, its distributors or its prospective recruits -- than Brees. In 2014, the Saints trained next to the AdvoCare Sports Performance Center in West Virginia; Brees lends his imprimatur to a line of DB9 nutrition bars and supplements. In one commercial (like several AdvoCare spots, the ad ran on ESPN), Brees appears on-screen in a suit, talking to the camera as pictures of families flash behind him. "I've seen product results, and so have thousands of people who trust AdvoCare," he says in the ad. "And the financial benefits can be just as rewarding for those who want more and decide to build their own AdvoCare business."

This pitch -- the promise that if you sign up for AdvoCare, you can reap "rewarding" financial results -- draws tens of thousands of new distributors every year. But an Outside the Lines/ESPN The Magazine investigation has found that few of those salespeople will ever achieve that vision. In reality, only a tiny fraction of AdvoCare members earn anything close to a modest income, even as they're pressured by higher-ranking distributors to keep buying inventory. "They plant the seed that you're gonna make money -- life-changing money," says Gabriel Chavez, who joined in 2010.

And while the company claims its primary objective is selling products, many of its distributors tell a different story. ESPN interviewed more than 30 current and former salespeople, the vast majority of whom said their focus, and the focus of their superiors, was on recruiting other distributors. These new members, many of whom are drawn to the business' strong religious culture or convinced of its credibility by its ties to the sports world, infuse the company with new funds -- money that ultimately flows up to the powerful people who walk the stage at Success School.

Chavez, who lives in Sierra Vista, Arizona, sat in the crowd when Brees spoke three years ago. He had been reluctant to fly to Texas for the event, which cost $119, but he says his superiors pushed him to make the trek. "They told me, 'Put it on your credit card. If your family doesn't support you, go anyways,'" he says. Friends and family members who raise questions about AdvoCare are labeled "dream killers" by other salespeople, according to several distributors.

By 2013, Chavez had spent three years trying to build an AdvoCare business. He had taken out a loan on his 401(k) and quit his government job, dropping $15,000 on products that he struggled to sell. He had hosted innumerable parties in his living room, handing out samples to reluctant attendees, and printed business cards with Brees' face on them. He barely broke even -- but he kept at it, convinced that someday he would be the one on AdvoCare's stage.

"You're always chasing the dream," he says. "And it never comes."

With Saints quarterback Drew Brees and other athletes leading the way, AdvoCare is using its sports ties to build a nutrition empire. But is the company really pushing false hope? Tom Farrey reports.Paul Spinelli/AP Images

ADVOCARE IS HEADQUARTERED in a sleepy office park in Plano, Texas, in a nondescript building with tinted windows. In the lobby, just inside the front door, the company has installed a bust of its founder, Charlie Ragus. A tall, charismatic Louisiana native who was briefly with the Kansas City Chiefs, Ragus died in 2001; there are photographs and paintings of him scattered throughout the office. "He wanted to start a company based on what he thought would be the best way to have a direct-sales business," says Allison Levy, AdvoCare's general counsel. "He loved this industry and was very passionate about having quality nutrition personally, and he just thought it was a real need for our country."

Levy, who is sitting across from a framed Brees jersey, avoids the phrase "multilevel marketing." She says she prefers "direct sales" because it's "a better definition and a better word choice for what we do."

It's also less controversial. While MLMs do rely on direct sales of products to customers, they also pay their salespeople commissions based on their recruits' purchases and, in turn, on the purchases of their recruits' recruits. These chains -- known as "downlines" -- continue to grow as long as members sign new salespeople, so some distributors can reap significant earnings without selling much on their own. This innovation, which kept MLMs afloat as traditional direct sellers fizzled out (remember encyclopedia salesmen?), also sent some companies down a slippery legal slope. Because MLMs reward people for recruiting others, they can run the risk of mutating into pyramid schemes -- illegal scams in which new members, who often make big initial buy-ins, are constantly sought so their money can be funneled up to the original members.

The industry blossomed in the 1980s, after the Federal Trade Commission ruled that Amway, now one of the biggest MLMs in the world, was a legitimate business. Ragus, who cut his teeth at an MLM called Herbalife, started his own operation, Omnitrition International, in 1989. Three years later, a group of former Omnitrition distributors would sue both Ragus and the company, alleging that it was a pyramid scheme. But by then -- the case was ultimately settled -- Ragus had already left. In 1993, he launched yet another MLM, AdvoCare.

Ragus decided early on that AdvoCare would focus on sports, and he enlisted coaches from nearby Southern Methodist University to work for him. One of AdvoCare's earliest distributors, Bruce Badgett, says the company's top salesmen made dozens of trips to NFL locker rooms, forging handshake deals with strength coaches for the Chiefs, Cowboys and Oilers. Occasionally, he says, they even set up the players' wives with lucrative distributorships. (The company denies that this practice occurs.) AdvoCare's sports ties "gave us credibility with every person -- every mom who has a son playing football," Badgett says.

Like other MLMs, AdvoCare created a ladder system for its salespeople; in order to climb the ranks -- which range from "advisor" to platinum -- and earn bigger bonuses, members had to recruit. Badgett, along with several other distributors who joined AdvoCare in its early years, rose to the pinnacle, earning millions. At one point, he says, he presided over a downline of more than 30,000 people, collecting commissions on sales from members many levels beneath him. In 1999, he and his wife bought a ranch in Oklahoma and named it AdvoCare Acres, branding their horses with the company's logo, a swooping A.

But after years of brisk growth, the company's fortunes began to tumble in the early 2000s, when Ragus passed away. In 2002, AdvoCare cut a popular product containing ephedra, which the U.S. Food and Drug Administration later banned in supplements, citing the risk of heightened blood pressure and strokes. Gross sales, which hit $260 million that year, plummeted to $110 million in 2005. Soon after, AdvoCare took public criticism for marketing a caffeinated energy drink to children ages 4 to 11. (While AdvoCare hasn't endured many product-related complaints, the firm was involved in one high-profile case: U.S. swimmer Jessica Hardy missed the 2008 Olympics after taking what she said was a supplement containing a banned substance. The company disputed her claim.)

By 2007, though, business began to boom again. When the economy collapsed, millions of Americans were either out of work or looking for extra cash; AdvoCare's message -- work from home, make more money, design your own life -- glimmered like an oasis. The company hired an experienced CEO and doubled down on sports marketing. In 2010, AdvoCare brought on Brees as its national spokesman; the company pays him for his appearances, gives him products and donates to his charity. Brees, who declined an interview with ESPN but answered questions via email, says he's been an AdvoCare user since 2002. "AdvoCare products have had a big role in my success as an NFL player and have certainly prolonged my career," he says.

The company also sponsors a NASCAR Sprint Cup car and in 2015 became the "official sports nutrition partner" of MLS. There's an NCAA basketball tournament called the AdvoCare Invitational and football's AdvoCare V100 Texas Bowl, both owned and broadcast by ESPN. The network also owns the AdvoCare Texas Kickoff. (Independent of his role at ESPN, analyst Dr. Jerry Punch sits on the company's sports advisory council; NFL analyst Trent Dilfer is a former endorser. In a statement, ESPN said of the network's business with the company: "AdvoCare sponsors select ESPN-operated events and is also a sponsor across select ESPN platforms.")

William Keep, the dean of the College of New Jersey's School of Business, says these sports deals are crucial to MLMs because they legitimize murky companies to the outside world. "If you're inviting someone into a situation where they can't verify a lot, how do you help them feel better about the decision?" asks Keep, who has co-authored research on MLMs with an FTC economist. "You bring in these kinds of sponsorships."

One former distributor says she was taught by higher-ups to pretend like Brees was standing next to her whenever she pitched the business to potential customers. She can still recite the line she was fed: "If Drew Brees takes it, why wouldn't you?"

Brees, along with the other athletes who sign with the company -- Carli Lloyd, Sam Bradford and Wes Welker are all past endorsers -- are integral to a popular AdvoCare sales and recruitment technique called the "Bulletproof Shield." Distributors preach this method with the help of a chart: The salesperson sits in a bubble in the middle, flanked by "endorsements" and a "scientific and medical advisory board." The basic concept is that the distributor should deflect questions about the company by replying, "Well, I don't know about (X), but what I do know is" -- and then referencing specific athletes or doctors who have vouched for AdvoCare. "You sell the products and the opportunity with the heart and the eyes, not extensive knowledge," explains one training manual.

Levy denies that the technique encourages deception. "The real purpose is to make sure that distributors aren't making anything up, and they refer back to the company," she says.

The inventor of the Shield is a triple-diamond-level distributor named Danny McDaniel, a pastor and former high school football coach who claims to earn a "substantial multimillion-dollar income" through AdvoCare. In one video, McDaniel teaches salespeople how to react if someone asks whether the company is a pyramid scheme. "You could say, 'I don't know a whole lot about those pyramid deals, but here's what I do know." He flips open an AdvoCare magazine, pointing to pictures of Welker and Brees. "I don't think people like that want to be involved in some pyramid deal."

THE NUMBERS BEHIND THE DREAM

AdvoCare and its athlete endorsers pitch the company as a way to change lives and achieve "financial freedom." Salespeople can make money by selling products, though the big bucks come from recruiting members. But the odds are long. Of AdvoCare's 517,666 salespeople in 2014, only 0.54 percent made $10,000 from the company and just 0.06 percent exceeded $100,000. Here are the numbers from that year, the most recent available. All data from AdvoCare's official 2014 income disclosure statement.

LORI CROSSAN LIVES at the end of a dirt road in Shelton, Washington, a tiny logging community of less than 10,000. For 17 years, she worked as a mortgage lender, making "really good money," the kind of money that allowed her to pay for traveling soccer teams and expensive clothes for her kids. Then the real estate market collapsed, and her income dried up.

When one of her friends told her about AdvoCare a few years ago, she was skeptical. But the friend kept calling and inviting her to parties. "She said, 'You've been heavy on my heart. I hope you'll be there,'" recalls Crossan. Eventually, she caved, dragging her husband to a mixer at the woman's house. She remembers everything from that night: the whiteboard, the Drew Brees poster, the cups of an energy drink called Spark. Before the meeting was over, they had dropped a few hundred dollars on a pair of 24-Day Challenges, weight-loss programs that bundle the company's shakes and supplements.

Several days later, a DVD arrived in their mailbox. They watched a video of a younger couple driving a golf cart around their expansive property, boasting about how they had quit their jobs and sent their sons to private school. The Crossans were mesmerized. They decided to enter at the "advisor" level, purchasing more than $2,000 worth of products in order to gain access to a 40 percent discount. (Top distributors pitch this as "the fastest, most economic way" to build a business.) By then, Lori had gotten a job at a local utility company, but she was making significantly less than she did before the recession. "I wanted an income supplement," she says. "I wanted the lifestyle that we used to have."

When you become an AdvoCare distributor, you sign a long, complicated contract -- the latest version is 33 pages -- that outlines the company's pay plan. AdvoCare's products are generally pricier than their store-brand equivalents, but advisors can buy them at a discount to resell. (AdvoCare forbids distributors from using sites like Amazon or eBay; widespread availability would undermine the direct-selling model.) If advisors sign people up, they can earn up to 3.5 percent of the retail value of products bought by their recruits and the people below them, and receive bonuses for growing their downlines.

How AdvoCare works

Like many distributors, Crossan found it hard to sell the products. She says she moved only three 24-Day Challenges over the course of a year, two of which went to her sister, so she tried to recruit other advisors. This too proved challenging. "People don't have that kind of money in a small logging town," she says.

In order to qualify for commissions each month, AdvoCare distributors must achieve a certain amount of sales volume, a mandate that drives some members to purchase products for the sake of meeting the quota. Crossan wasn't bringing on new recruits, but she kept buying products, goaded by the people above her in the organization. "They said, 'You gotta spend money to make money,'" she says. She bought AdvoCare-issued magazines; she listened to prerecorded calls, trying to glean tips from her superiors. At one point, she clicked on a training video that offered scripts for inviting people to mixers. One line jumped out. "It said, 'I've been thinking about you, and you've been heavy on my heart.'"

She pauses. "That was used on me."

While AdvoCare provides some training material -- the company's newest DVD says it "offers the average American the chance to make an above-average income" -- many distributors told ESPN they were taught how to recruit by other, higher-ranking members. These salespeople aren't technically employees of AdvoCare (they're independent contractors, like all distributors), but they're the face of the business. They appear on the company's website and speak at its conferences; they're idolized by low-level distributors. Very few members make it to this level -- last year there were only 46 platinum distributors, the highest grade, according to AdvoCare -- and it's unclear how many of them simply remain there year after year.

One distributor's slideshow depicts page after page of top salespeople: a former baseball coach and teacher (it says they make $12,000 a month), an ex-police officer and teacher ($60,000 a month) and a pair of former cheer coaches ($35,000 a month). Former distributors say presentations like this are frequently shared with new recruits. "They're showing you pictures of people in mansions and on extravagant vacations," says Lisa Ranieri, a distributor who pursued the business for several years before giving up.

When Crossan and her husband did their taxes after leaving AdvoCare in 2011, they realized they had spent more than $6,000 on products, most of which had expired before they decided to return them. (AdvoCare gives salespeople 30 days to return products or up to a year if they forfeit their distributorship.) Unlike people who had started a business, they had built no equity -- it was just money down the drain. "I was like, 'Holy crap -- we went through our savings,'" she says. "'What on earth did we do?'"

AdvoCare tells distributors to give prospects an official income disclosure statement, which shows how many salespeople reach each level of the company. The numbers are stark: According to the latest statement, the company had 517,666 distributors in 2014, and just 1,209 of them -- 0.2 percent -- earned more than $25,000 that year; 95 percent earned $1,000 or less. Those figures don't include profits from members' product sales, but they also don't include expenses, which several distributors say outweigh retail profits.

Levy, the general counsel, says many distributors aren't actually trying to make money -- they're just in it for the markdown: "We have hundreds of thousands of people that join our business, most of them primarily for a product discount." But even if you include only "active distributors," i.e. salespeople who have received checks based on their recruits' purchases or online sales through personal websites they've set up and are ostensibly pursuing the business opportunity, the number of distributors earning more than $25,000 rises to only 0.8 percent. (Levy says many of these people also signed up for the discount.)

One former distributor, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, says she did make a decent income through AdvoCare. But she acknowledges that almost no one in her downline made money. "It nauseates me to think of the people who spent $3,000 and didn't make a dime, because they believed me -- and the goal, and the dream," she says. "You catch people in a bad spot who maybe have hope that this could be a way for them to pay for their credit card and their kids, and you exploit them. That's the bottom line."

Several relatives of AdvoCare distributors told ESPN that when they tried to discuss these statistics with their family members, they were shunned. One man, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, says his sister stopped speaking with him when he questioned the business. "She won't have a conversation about it," he says. "We used to be able to talk."

Robert FitzPatrick, an industry critic who has consulted on federal cases involving pyramid schemes, says he's heard similar stories about MLMs. "I have people constantly contacting me -- 'My son wants to drop out of college, my spouse wants to mortgage the house. They won't listen to me, they won't talk about due diligence.'" FitzPatrick says that across the industry, veteran distributors enforce such behavior, urging new members to segregate themselves. "At the core," he says, "they're cults."

NASCAR driver Trevor Bayne, who drives the No. 6 AdvoCare car says, "It's a great product, and I really do feel like it helps me in the race car." Jeff Gross/Getty Images

ON A SATURDAY morning in January, hundreds of AdvoCare distributors trickled into a hotel ballroom in Orlando, lining up for photographs with top salespeople as Jon Bon Jovi songs throbbed from speakers. Many were dressed in company gear: AdvoCare polos, rubber bracelets and T-shirts studded with rhinestones spelling out the company name. It was 9:30 a.m., but no one was drinking coffee; Spark, the powdered energy drink, was the caffeinated beverage of choice. Several distributors were pouring packets of the stuff into their water bottles, leaving its chalky scent lingering in the air.

In addition to its annual Success School, AdvoCare holds a series of smaller conventions like this one in 10 cities across the country. Tickets to the Orlando event cost $69. As the lights dimmed, the crowd sat down, then immediately stood up again when Rick Loy, a longtime AdvoCare executive, strolled out. "Every one of you is a champion!" roared Loy, a petite, white-haired man with the silky drawl and sweeping gestures of a Southern preacher. Loy asked the first-time attendees in the audience to stand up, and nearly three-fourths of the audience rose to their feet. "You are the next generation," he said.

Over the next six hours, more than a dozen people spoke onstage; most received standing ovations. Loy interviewed a member of the company's scientific board, a Florida-based surgeon, and one of the athletic endorsers, a baby-faced NASCAR driver named Trevor Bayne. ("It's a great product, and I really do feel like it helps me in the race car," said Bayne, who drives the No. 6 AdvoCare car.) The company played clips of top distributors speaking reverentially about Ragus, its founder. One man called him "the Vince Lombardi of direct sales."

A platinum distributor named Brock Meadows gave a presentation on the income disclosure statement, the document that shows how many distributors make it to each level. "You paint vision with this document. You breathe life into it. You present hope and opportunity," he said. Like many of the speakers, Meadows was tall and muscular, with the sort of no-nonsense brush cut favored by high school football coaches. "This is the equal and fair opportunity to walk into the arena of life and throw down."

“They plant the seed that you're gonna make money -- life-changing money.”

- Gabriel Chavez, who joined in 2010

Throughout the afternoon, numerous distributors -- mostly couples, deeply tanned and dressed in business attire -- delivered short, emotional speeches. One woman, a silver distributor from South Carolina, wept as she described how she had to send her son to day care because of her job. "My kids didn't ask to be raised by other people," she said. Minutes later, another speaker, also a working mother, broke down in tears.

Before long, a pattern emerged. The couples told tales of transformation: Before AdvoCare, they were overweight, depressed, resentful of their jobs, resentful of each other. After, they were happy. The audience exploded when a local couple, Mike and Sarah Ferro, appeared onstage. According to the income disclosure chart, platinum-level distributors like the Ferros made an average of $1.2 million in 2014. Mike, a former water-ski instructor, paced the stage in a dark suit, his AdvoCare pin glittering from the lapel. "People don't know how much you know until they know how much you care," he said. A murmur rippled through the crowd. "Powerful, right?" Near the back, a young woman typed his words on her phone, then paired them with a nature scene and posted the image online.

At the event, the Ferros didn't explain, in detail, how they actually sell AdvoCare. But they provide plenty of information elsewhere. In addition to running a Facebook group with nearly 12,000 members, the couple operate a website that's replete with training materials. One PowerPoint, titled "How to Present AdvoCare Properly," says: "Health Crisis + Financial Crisis = Opportunity." It goes on to claim that the direct-sales industry has "More Millionaires than any other industry." (After being presented with questions about the Ferros' site by ESPN, AdvoCare asked the couple to take several documents down.)

Though the speakers in Orlando only hinted at their wealth -- AdvoCare's legal department tells salespeople not to make monthly income claims, which could spur lawsuits accusing them of deceptive marketing -- distributors in the audience were more direct. One woman told me she made $12,000 a month last year. After I explained that I was writing a story about AdvoCare, she recommended a career change. "You're gonna want to after this. Lots of young people make money." She pulled a few Spark packets from her purse and fanned them out, offering them as samples.

TEAM ADVOCARE

Securing athlete endorsers is a key part of AdvoCare's model. The company lists more than 65 of them on its website, so while Drew Brees is unquestionably its face, the roster is deep.

DREW BREES NFL quarterback, Saints

PHILIP RIVERS NFL quarterback, Chargers

ALEX SMITH NFL quarterback, Chiefs

JASON WITTEN NFL tight end, Cowboys

ANDY DALTON NFL quarterback, Bengals

DOUG FISTER MLB pitcher, Astros

KOLTEN WONG MLB infielder, Cardinals

LEE JANZEN Champions Tour and PGA golfer

TREVOR BAYNE NASCAR Sprint Cup driver

JOE PAVELSKI NHL forward, Sharks

WHEN ASKED WHETHER he's familiar with AdvoCare's multilevel marketing model, Brees, like Levy, offers a corrective: "It's actually a direct-sales business model," he says, noting that many distributors, like his wife, sell the products "casually." He says he's comfortable with AdvoCare salespeople using his name to legitimize the business. "In fact," he adds, "I take it as a great honor and responsibility to uphold the values of the company."

Every MLM fosters its own culture. Some promote glitz and glamour; others, like AdvoCare, push a more wholesome image. "Drew is the kind of person, really on the field as well as off, that embodies who AdvoCare is and what our brand is all about," Levy says. That brand aligns perfectly with the quarterback's reputation: Family man. Philanthropist. Devout Christian.

While AdvoCare doesn't broadcast its religious side to the public -- Levy says it is a secular company -- former distributors say Christianity permeates the culture. The company's sacred text, Ragus' "Guiding Principles," opens with the admonition: "Honor God through our faith, family and friends." Several distributors say AdvoCare thrives inside churches, where pre-existing networks make it easier for distributors to preach the good news of multilevel marketing. "There are some congregations here in Dallas where, if you participate in some of the groups, you will participate in AdvoCare," one former member says.

The intermingling of business and faith has caused turmoil inside the business. Lance Wimmer, a consultant who was hired to help turn around the company in 2005, says the top distributors were divided by religion; the devout churchgoers held more power and wielded it over others. At one meeting in Dallas, he says, some influential salespeople confronted him about his own faith (a former distributor corroborated this account). "They started asking me a lot of questions like, 'Are you a religious guy? What religion are you? Do you believe in this?'" Wimmer left the company after a few months.

For some members, the pressure to conform -- in dress, speech and, above all, godliness -- could be agonizing. "Religion was brought up at every event or meeting I attended," says Shereef Kamel, a former high-ranking distributor. "They'd always say: 'This is your calling. You're serving others. It's the Christian thing to do.'"

Kamel, who runs a youth basketball school in Plano, was terminated in 2014 after he clashed with a member above him, who sent him a racist text, he says. (Kamel sued and AdvoCare countersued; the company declined to comment on ongoing litigation.) The company has cut off numerous members for various violations, causing their downlines to "roll up" to higher-ranking salespeople, who then profit from the extra commissions. Some exiles have sued; Badgett, the distributor who built the ranch, was terminated in 2006 and won a $1.8 million judgment against the company.

Before he was kicked out, Kamel had built a sizable downline. "I got my friends into it, and all the while I hated myself," he says. "I felt like a con artist."

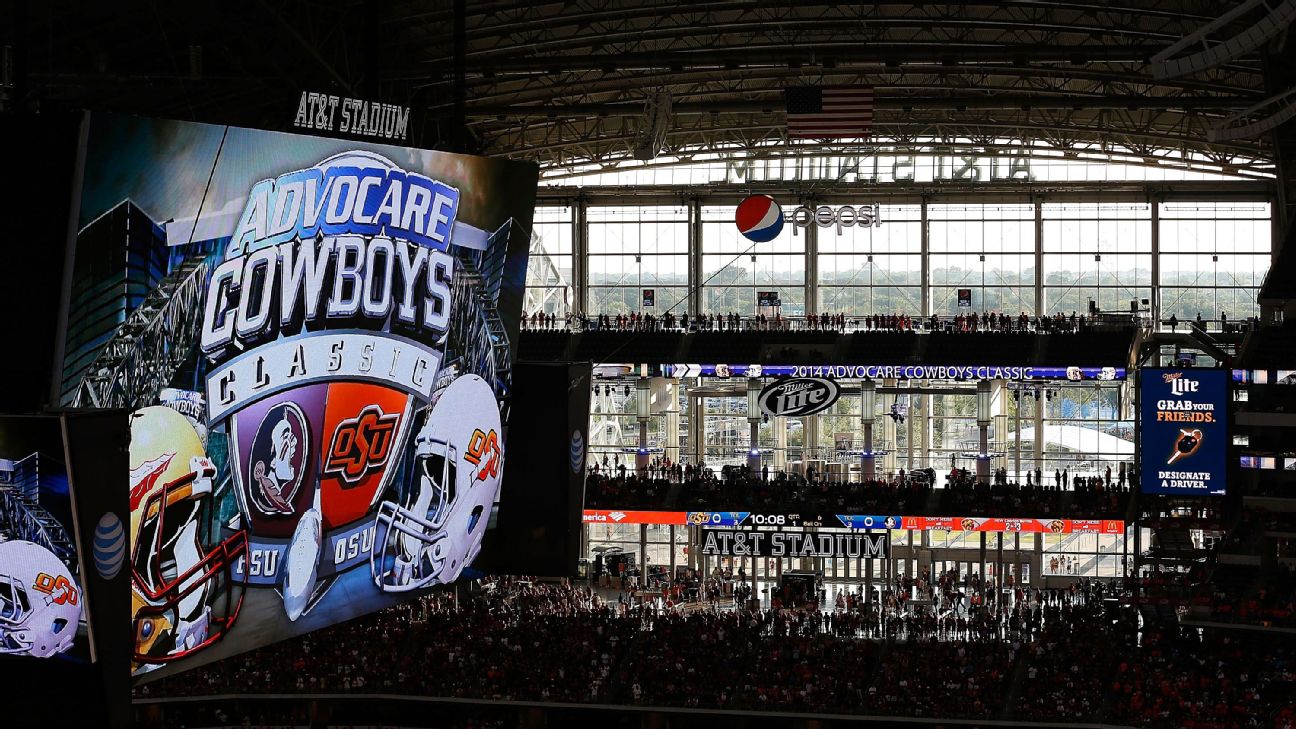

AdvoCare's sports ties run deep, from its high-profile athlete endorsers to its sponsored events, like the AdvoCare Cowboys Classic at AT&T Stadium in Dallas in 2014. (The game was broadcast by ESPN on ABC.) Tom Pennington/Getty Images

OVER THE PAST three decades, the government has brought only a handful of cases against MLMs. Critics say the companies escape scrutiny because they're impenetrable; the industry's trade group, the Direct Selling Association, successfully lobbied the FTC to shelve new transparency rules in 2012. But the tide may be turning. In 2014, the FTC announced it was investigating Herbalife. Last summer the agency asked a federal court to halt operations of another outfit, Vemma Nutrition Company.

In its complaint, the FTC called Vemma an illegal pyramid scheme. The agency -- which declined to comment on AdvoCare -- accused Vemma's salespeople of misrepresenting how easy it is to make money, pressuring new recruits to "buy in" to the plan and prioritizing recruiting over retailing. Keep, the dean of the College of New Jersey's School of Business, says there are numerous similarities between Vemma and AdvoCare, whose "compensation plan strongly incentivizes recruitment," he writes.

“You catch people in a bad spot who maybe have hope that this could be a way for them to pay for their credit card and their kids, and you exploit them.”

- a former distributor

When asked point-blank if the company is a pyramid scheme, Levy responds: "Absolutely not. AdvoCare is a business based on terrific real nutritional products that are sold through a direct-sales channel." She adds that the company has checks in place to ensure that its distributors are actually selling products. Like other MLMs, AdvoCare decrees that, in order to qualify for commissions, distributors must sell to five different customers every two weeks and retail or consume at least 70 percent of the products they purchase. Keep points out that distributors could be loading up on their own purchases -- hardly a sign of outside demand.

AdvoCare doesn't disclose what percentage of its products are sold to people who aren't members. "[Distributors] don't necessarily report those to AdvoCare," Levy says. "But we do know that our products are extensively sold and consumed." The company points out that nearly 400,000 non-distributors have purchased products through its members' sites.

Several distributors told ESPN that they did sell some products. But most said they -- and their superiors -- put far more effort into recruiting. "It's absolutely 100 percent the business opportunity. No one falls in love with the product," says Kamel, who estimates that less than 5 percent of his downline turned a profit.

According to a 2004 survey conducted by the FTC, victims of pyramid schemes are less likely to complain than victims of any other type of fraud. MLM supporters say few grievances about the companies surface because they are doing nothing wrong; critics counter that discretion is baked into the business model. When people join these companies, they're often recruited by family or friends, and they go on to enlist others who are close to them. As a result, if they renounce the business, they're either renouncing their loved ones or admitting that they exploited them.

Former AdvoCare members say loyalty keeps distributors silent -- but so does shame, because people who struggle are told, over and over, that they simply aren't trying hard enough. "If you can't make money, they blame you," Crossan says. She remembers one of the mantras that was drilled into her: "They said, 'You can't do the minimum and expect the maximum.'"

Since joining AdvoCare, Brees says he's been stopped on the streets by "literally thousands of people" who tell him how the company has changed their lives: "I have literally NEVER had a single person come up to me and say anything negative about AdvoCare products or the business model." He adds, "I see the lives that it changes, not only as a direct result of taking the products but the financial independence it gives many of its distributors.

"Why are all these people involved in AdvoCare?" he continues. "Because it's a viable business, and they believe in the products, what they are selling and in AdvoCare. And so do I."