An ancient scroll that was crushed and burned in a blaze that engulfed an entire town more than 1,400 years ago has been digitally unfurled and identified as a copy of the book of Leviticus.

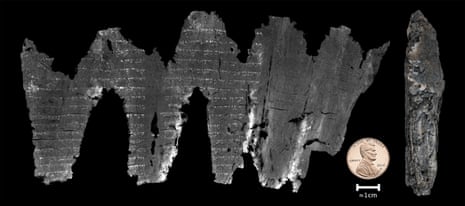

Researchers made the discovery after computer scientists used a ground-breaking procedure called “virtual unwrapping” to flatten out digital sheets of the carbonised document and read the Hebrew words originally inscribed on the parchment in AD300.

Based on 3D x-ray scans of the charred remains, the computer reconstruction reveals the ancient writing with such clarity that scholars have read entire verses of the work and found its place in the history of important biblical texts.

No more than a lump of disintegrating charcoal, the scroll is so fragile that it has barely been touched since it was discovered in 1970. It was found in the holy ark of a synagogue in En-Gedi, a town on the western shore of the Dead Sea that was destroyed by fire around AD600.

“We know now that the scroll from En-Gedi is biblical. We’ve identified it as the same text from the book of Leviticus,” said Brent Seales, a computer scientist who led the research at the University of Kentucky. “Anything that is still inside the scroll is now possible to view.”

The effort to read the ancient text began when researchers at the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) in Jerusalem took high resolution x-ray scans of the En-Gedi scroll and the older Dead Sea Scrolls that were found in the Qumran caves in the 1940s and 50s in what is now the West Bank.

Pnina Shor, head of the Dead Sea Scrolls Project at the IAA, sent the x-ray images to Seales to study, but she was not optimistic that he would extract any useful information from them. “It was a shot in the dark,” she said.

Seales ran the En-Gedi images through a four step procedure. The first creates a digital map of the crinkled contours of different regions of charred parchment. The second marks where ink was used, as revealed by bright spots in the x-ray images. The computer then flattens the regions out and merges them into one complete image. In the case of the En-Gedi scroll, writing showed up in the scans because the author used an ink that contained metal, probably iron or lead.

Using the system, the US team unwrapped five pages of the ancient scroll. Though Seales does not read Hebrew, it was clear that markings on the pages were written words. To find out what they said, he sent the images back to the team in Jerusalem. When Shor replied, she said they had not only read the text, but identified it as the book of Leviticus, the third book of the Hebrew bible. “At that point we were jubilant,” Seales said. “The En-Gedi scroll is proof positive we can potentially recover whole texts from damaged material, not just a few letters or a speculative word.”

One sheet of the scripture contains 35 lines of text, each with a similar number of words. The Hebrew text is made up only of consonants, as vowels did not come into use until later on. Describing the team’s work in the journal Science Advances, Seales writes: “Without our computational pipeline and the textual analysis it enables, the En-Gedi text would be totally lost for scholarship, and its value would be left unknown.”

The scientists now hope to read other ancient artefacts that have been damaged in the course of history. High up on their wish list is a library of Roman scrolls that were burned and buried when the town of Herculaneum was destroyed in the eruption of Vesuvius nearly 2000 years ago. Vito Mocella at the National Research Council in Naples has already read single letters from the scrolls.

“Although this approach is bespoke at present, this type of technology will become more and more available in the future, potentially unlocking ancient libraries thought lost forever,” said Melissa Terras, Director of the UCL Centre for Digital Humanities. Her team has used digital techniques to read The Great Parchment Book, a 17th century survey of Irish estates that was also damaged by fire.

Last year, Rubina Raja at Aarhus University in Denmark used computer software to read inscriptions on an 8th century rolled silver scroll from Jerash in Jordan. “Digital imaging and unfolding of ancient objects has the potential to read all these things lying around in museums and in storage, whether they are metal, papyri and even textiles,” she said.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion