So. The child psychologist across the desk has just told you that your three-year-old is "presenting behaviour consistent with that of an individual on the autistic spectrum". You feel trepidation, sure, a foreboding that your life as a parent is going to be much tougher than the one you signed up for, but also a dash of validation. At least you now have a 10-page report to show to friends and relatives who have been insisting that boys are slower than girls, or that late language is to be expected in a bilingual household, or that you were just the same at that age. It's a relief that your child's lack of eye contact, speech and interest in picture books now has a reason and a name. You send some generic emails to people who ought to know first containing the words "by the way", "looks like", "has autism", "but don't worry" and "confirmed what we thought anyway". The replies come quickly but read awkwardly: condolences are inappropriate in the absence of a corpse, and there aren't any So Sorry Your Offspring Has Turned Out Autistic e-cards. People send newspaper cuttings about autism, too – about how horse-riding and shamans in Mongolia helped one kid, about a famous writer whose son has autism and is doing fine, about a breakthrough diet based on hemp and acacia berries. The clippings go in the compost.

You read books to learn more – until now, the closest you've come to autism is watching Rain Man or reading The Curious Incident Of The Dog In The Night-Time. Autism proves to be a sprawling, foggy and inconsistent field. Causes are unknown, though many careers are fuelled by educated guesses. MMR is the elephant in the room, but you'll get to know a number of people with autism who never had the injection, so you draw your own conclusions, like everyone else – until such time as harder data emerges from the vast control group of MMR refusers' children created by the scare. Symptoms of autism appear to be numerous. Some are recognisable in your own son, but just as many are not. You learn that luminaries such as Bill Gates have "high-functioning autism": "low-functioning" people with autism lead less visible lives. You hope for the best.

There's quite a marketplace for autism treatments, you find. Some sound rational, others quasi-deranged. One claims that autism is caused by allergens entering the bloodstream through a perforated bowel and inhibiting cerebral development. You FedEx a blood sample to a laboratory in York, and quite a long list of prohibited foods comes back, including lamb, kiwi fruit, pineapple, gluten, red meat and dairy products. Your family adopts the regime, and although you feel a little healthier, you see no change in your child. Ditto the benefits from the ionised water you've ordered from the US, which a friend passionately recommended. You feel a new pity for the medieval unwell, who limped from one shrine to another, hoping to find the right saint to pray to, when what they really needed was a quantum leap in medical science. Such a leap has not occurred in autism research yet.

Autism therapists enter your life. Some work for local care-providers, some are freelance; some are occupational therapy specialists, some focus on speech and language, some advocate Floortime™ (a play-based treatment), some "applied behaviour analysis" (rewards and measurements); some are evangelical about one approach, some take a more pragmatic "whatever works, works" approach.

You learn that treatment is called "intervention", and that while 10-15 hours a week are recommended, your local care-provider has the resources to offer only about 15 hours per year – and, after sickness and staff training, this will become 10 hours. One afternoon, a therapist from the care-provider is so fazed by your kid headbanging the kitchen floor that she flees before the session is over, and you realise you'll have to pay privately. You don't begrudge the money – the therapist you find has a horse-whisperer's gift for teaching children with special needs – but 10 hours a week is going to cost upwards of £10,000 a year. (How much is Eton again?) Some is refundable, if the official criteria for the tutor are satisfied, but for the most part you're on your own. Therapy during school holidays is not repayable, because the authorities believe autism ceases to exist outside term time.

Things get challenging. Your sleep is broken and stays that way. Kids with autism don't really do bedtime – they keep going, Duracell bunny-style, until unconsciousness sets in, often after midnight: 3am "parties" are common, where your child wakes up refreshed and jumps on the bed for an hour, laughing and crying. After one rough night you take your kid out for a spin in the car to give your partner a rest – 45 minutes of nonstop screaming later you give up and come home. Worst is the headbanging – against the hard floor, up to a dozen times a day. Your kid's bruises are earning you dodgy looks at the supermarket checkout. It is suggested that you keep a self-harm diary to identify the triggers, but these seem numerous and obvious: hunger; tiredness; frustration at dead batteries in a toy; a scratched Pingu DVD; not being allowed to play with kitchen knives.

You're warned against stopping the headbanging by force, in case this reinforces the self-harm by teaching your kid that headbanging = attention + a hug, but you're also afraid of brain injury and concussion. A wise therapist suggests placing your foot between head and floor, so that the impact is softened. As your feet get tenderised, you recall an influential American psychologist who preached that autism is caused by "refrigerator mothers" not loving their children properly. You hope that Lord Satan has something special planned for that learned gentleman. You envy acquaintances who have hands-on family members living nearby, able and willing to roll up their sleeves and help: like many others, you and your partner are on your own. Self-pity, however, makes you feel wretched and is a rudeness to single parents coping with a child with autism while being forced by the bedroom tax to search for one-bedroom flats.

Your social horizon dwindles. Friends assure you, "Bring him over. It's fine – our place always looks like a bomb's hit it" but you know they'll be less laid-back when a curtain rail gets used as a gym bar and comes down in a shower of plaster. Babysitters, air travel, hotels and B&Bs are off the menu. You are offered respite care, but it feels too much like dumping your four-year-old among minimum-wage strangers in Mid Staffordshire, and turn down the offer. Soon after, you read about a teenager with autism who died at a nearby respite facility. He choked to death on a rubber glove and wasn't found until the morning. You feel a fuzzy anger at autism itself, for denying your kid so many childhood pleasures: making friends, trips to the cinema, birthday parties, a day at a theme park.

Your kid suffers from a period of acute hypersensitivity, when clothing appears to feel like cheese-graters, and sitting or even lying down to rest causes intolerable distress. People suggest massage oils, swinging your kid around at high speed, and waiting for the sunspots to subside. Others say, "Thanks for telling me" in a consoling tone of voice. A potty-mouthed Edinburgh friend says he hasnae got a fockin' clue how fockin' hard that must fockin' be fer all o'yer, which cheers you up a bit. The hypersensitivity lasts about a fortnight. That was the nadir.

Your kid turns five. One day, he traces a finger over the VW insignia on your car and remarks "V and W". A few days later, you hear him sing "Cork 96 FM" – the cheesy jingle of a local radio station, but it is pure music. Soon after, there's a cup held under your nose and the word, "Juice." Two weeks later your therapist brings your child into the kitchen to say, "Can I have apple juice, please?"

Life's still far from Mary Poppins – there's no dialogue as such, and while many people are tolerant, your partner reports unfriendly vibes from other mothers at the Jumping Beans Preschool Song and Dance Circle. Au revoir, Jumping Beans. The shoe shop lady rolls her eyes in contempt at your child's meltdown at the foot-measuring stool, and the owner of a hair salon doesn't hide what she thinks of such a big kid getting freaked out by buzzing clippers. Nonetheless, you are aware of your son growing into who he is. Life gets better in small increments. Your child likes standing on your feet to chop vegetables; baking; reciting long, half-clear chunks of Wes Anderson's Fantastic Mr Fox; gazing at the sky, fascinated, through the fingers of trees; and leaping with delight at the Archers omnibus theme tune every Sunday. One day your child replaces the name "Dora" with his own name in Dora The Explorer, and gives you a crafty smile to see if you noticed – a first joke. He is entranced by the numbers on the microwave display panel, and counts the stairs in English, Spanish and Japanese. One day you notice he has scored 79,550 points on a tricky iPad game, Doodle Jump. This is 50,000 points higher than the top score achieved by any "neuro-typical" member of the household.

Time to find a primary school. You take your child to the therapist at the local care-provider for an updated needs assessment. In due course you receive a list of what a primary school will need to provide: occupational therapy, speech and language work, and a one-on-one SNA (special needs assistant) within a special needs unit. You ask which schools in the area can provide all this. The therapist looks cagey and names two schools. School A is 20 miles away, school B is 30 miles away. Over the phone the principal of school A asks whether or not your son is verbal. You say, "A bit." The principal tells you they work with non-verbal children only, and wishes you a nice day. You visit school B, where the special needs unit has six places, though three are already filled. You realise that every five-year-old kid with autism from your half of the county has to compete for three places. The principal is impressive and her son has autism so she knows what's needed, but the application form warns that the school "upholds the Catholic ethos" and asks for the name of your parish and priest, if applicable. It isn't, and you doubt that 79,550 points at Doodle Jump will help a whole lot.

As you drive off, you think you can hear the distant thunk of your application form hitting the bottom of the bin, but that can only be imaginary. Later, you call the care-provider therapist to tell her you don't think your kid has a school to go to in September: what should you do now? She says, "Well, you might hear from school B." You say that you both know that won't happen, and ask what she would do if the shoe were on the other foot. You badger her into admitting that she has no idea. Later, you regret it. It's hardly her fault.

At the 11th hour the Department for Education sniffs legal action and media scrutiny, and realises it has to respond. Or maybe that's far too cynical; maybe the policy-makers were motivated by altruism and concern. A nearby primary school is approached with a proposal to host a new unit for children with autism. The principal, whom you've known for a few years, is dedicated, focused and indefatigable. She agrees, and thanks to her, your six-year-old has a school when September rolls around. Everyone involved is on a learning curve, but the underfunded, underpaid team do a great job. Your kid has classmates for the first time, and by hook and by crook each student acquires an iPad. These prove to be godsends. Beside the specialist apps, the built-in video camera allows the teacher to record your child achieving goals in the classroom that you never imagined were attainable. You and your child love watching these video clips at home.

Two other things help a lot: an analogy and a book. The analogy comes via a Jewish friend's rabbi, and compares expectations of parenthood to planning a long sojourn in Italy. Prior to your holiday, you read up about Italy, speak with experts on Italy, plan your route, gen up on Italian and anticipate the pleasures of your time there. Having a life-redefining diagnosis – like autism, Asperger's, Down's, whatever – is like getting off the plane and finding yourself not in balmy, romantic Rome but… Schipol Airport, in Holland. What the hell? My wife and I booked our holiday in Italy, like everyone else. But time passes and the penny drops that hankering for Italy is stopping you from seeing Holland. Your attitude shifts. You begin to discover that Holland possesses its own singular beauty, its own life-enriching experiences.

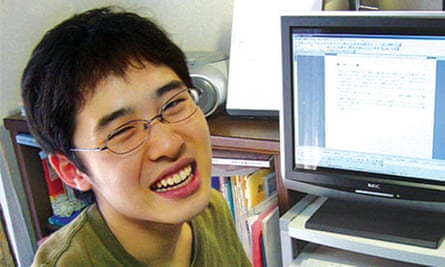

The book that helped me the most to "think Dutch" about my own son's autism was written by a 13-year-old Japanese boy called Naoki Higashida. It's called The Reason I Jump. The author would be classed as severely autistic, and writes by pointing to a "cardboard keyboard", one character at a time. A helper transcribes the characters into words, sentences and paragraphs. Part one adopts a Q&A format, where the author answers questions about life with his condition. Reading it was illuminating and humbling; I felt as if my own son was responding to my own queries about what it's like to live inside an autistic mind. Why do you have meltdowns? How do you view memory, time and beauty?

For the first time I had answers, not just theories. What I read helped me become a more enlightened, useful, prouder and happier dad. Part two of the book is a story, I'm Right Here, about a boy called Shun who discovers he's dead and can no longer communicate.

My wife and I translated The Reason I Jump clandestinely, just for our son's therapists, but when my publishers read the manuscript, they believed the book might find a much wider audience. For me, Naoki Higashida dissolves the lazy stereotype that people with autism are androids who don't feel. On the contrary, they feel everything, intensely. What's missing is the ability to communicate what they feel. Part of this is our fault – we're so busy being shocked, upset, irritated or looking the other way that we don't hear them. Shouldn't we learn how?

'Living is a battle': growing up with autism, by 13-year-old Naoki Higashida

When I was small, I didn't even know I had special needs. How did I find out? By other people telling me I was different and that this was a problem. True enough. It was very hard for me to act like a normal person, and even now I still can't "do" a real conversation. I have no problem reading books aloud and singing, but as soon as I try to speak with someone, my words just vanish. I can't respond appropriately when I'm told to do something, and whenever I get nervous I run off from wherever I happen to be. So even a straightforward activity like shopping can be really challenging if I'm tackling it on my own.

During my frustrating, miserable, helpless days, I've started imagining what it would be like if everyone was autistic. If autism was regarded simply as a personality type, things would be so much easier. Thanks to training, I've learned a method of communication via writing. Problem is, many children with autism don't have the means to express themselves, and often even their own parents don't have a clue what they might be thinking. So my big hope is that I can help a bit by explaining, in my own way, what's going on in the minds of people with autism.

Why do people with autism talk so loudly and weirdly?

People often tell me that when I'm talking to myself my voice is really loud, even though my voice at other times is way too soft. This is one of those things I can't control. It really gets me down.

When I'm talking in a weird voice, I'm not doing it on purpose. Sure, there are times when I find the sound of my own voice comforting, when I'll use familiar words or easy-to-say phrases. But the voice I can't control is different. This one blurts out, not because I want it to: it's more like a reflex. When my weird voice gets triggered, it's almost impossible to hold it back – if I try, it hurts, almost as if I'm strangling my own throat.

Why do you ask the same questions over and over?

It's true, I always ask the same questions. "What day is it today?" or "Is it a school day tomorrow?" The reason? I very quickly forget what it is I've just heard. Inside my head there isn't such a big difference between what I was told just now and what I heard long ago.

I imagine a normal person's memory is arranged continuously, like a line. My memory, however, is more like a pool of dots. I'm always "picking up" these dots – by asking my questions – so I can arrive back at the memory that the dots represent.

But there's another reason for our repeated questioning: it lets us play with words. We aren't good at conversation, and however hard we try, we'll never speak as effortlessly as you do. The big exception, however, is words or phrases we're very familiar with. Repeating these is great fun. It's like a game of catch. Unlike the words we're ordered to say, repeating questions we already know the answers to can be a pleasure – it's playing with sound and rhythm.

Why do you do things you shouldn't, even when you've been told a million times not to?

It may look as if we're being bad out of naughtiness, but honestly, we're not. When we're being told off, we feel terrible that yet again we've done what we've been told not to. But when the chance comes once more, we've pretty much forgotten about the last time. It's as if something that isn't us is urging us on.

You must be thinking: "Is he never going to learn?" We know we're making you sad and upset, but it's as if we don't have any say in it. Please, whatever you do, don't give up on us. We need your help.

Do you prefer to be on your own?

I can't believe that anyone born as a human being really wants to be left all on their own. What we're anxious about is that we're causing trouble for the rest of you, or even getting on your nerves. This is why it's hard for us to stay around other people.

The truth is, we'd love to be with other people. But because things never, ever go right, we end up getting used to being alone. Whenever I overhear someone remark how much I prefer being on my own, it makes me feel desperately lonely. It's as if they're deliberately giving me the cold shoulder.

Why do you make a huge fuss over tiny mistakes?

When I see I've made a mistake, my mind shuts down. I cry, I scream, I make a huge fuss, and I just can't think straight about anything any more. However tiny the mistake, for me it's a massive deal. For example, when I pour water into a glass, I can't stand it if I spill even a drop.

It must be hard for you to understand why this could make me so unhappy. And even to me, I know really that it's not such a big deal. But it's almost impossible for me to keep my emotions contained. Once I've made a mistake, the fact of it starts rushing towards me like a tsunami. I get swallowed up in the moment, and can't tell the right response from the wrong response. To get away, I'll do anything. Crying, screaming and throwing things, hitting out even… Finally, finally, I'll calm down and come back to myself. Then I see no sign of the tsunami attack – only the wreckage I've made. And when I see that, I hate myself.

Why do you repeat certain actions again and again?

It's like our brains keep sending out the same order, time and time again. Then, while we're repeating the action, we get to feel really good and incredibly comforted.

I feel a deep envy of people who can know what their own minds are saying, and who have the power to act accordingly. My brain is always sending me off on little missions, whether or not I want to do them. And if I don't obey, then I have to fight a feeling of horror. For people with autism, living itself is a battle.

Why are your facial expressions so limited?

Our expressions only seem limited because you think differently from us. It's troubled me for quite a while that I can't laugh along when everyone else is. For a person with autism, the idea of what's fun or funny doesn't match yours, I guess. More than that, there are times when situations feel downright hopeless to us – our daily lives are so full of tough stuff to tackle. At other times, if we're surprised, or feel tense or embarrassed, we just freeze up and become unable to show any emotion whatsoever.

Criticising people, winding them up, making idiots of them or fooling them doesn't make people with autism laugh. What makes us smile from the inside is seeing something beautiful, or a memory that makes us laugh. This generally happens when there's nobody watching us. And at night, on our own, we might burst out laughing underneath the duvet, or roar with laughter in an empty room… When we don't need to think about other people or anything else, that's when we wear our natural expressions.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion