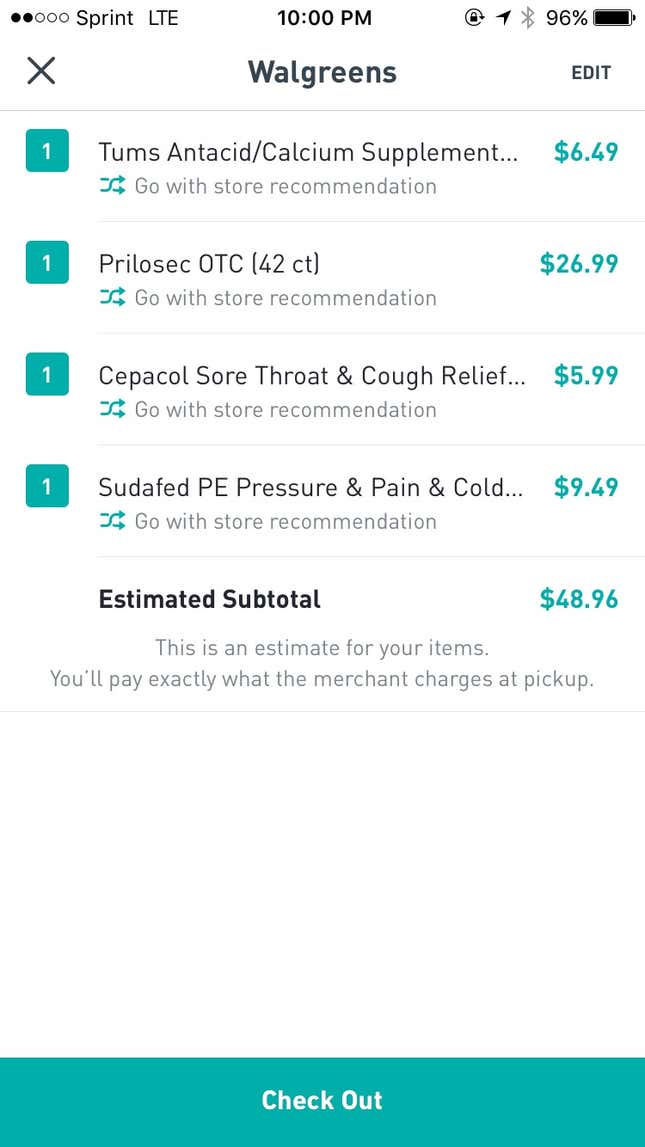

In late June, Shawn Cook had a cold and needed some cough medicine. The mobile game developer turned to on-demand delivery startup Postmates to make the run to Walgreens for him in Los Angeles that Tuesday night. Postmates estimated that four of the five items he ordered, which were listed in its Walgreens inventory, would ring up to $48.96. Cook would also pay a delivery fee, Postmates’ 9% service fee, and whatever his fifth item—a “custom” request for “Ibuprofen/Advil, the largest one”—wound up costing.

The total was bound to be higher. But $94.24 was a shock.

“It was the worst,” Cook says. “After I closed the door, I was like wait, this isn’t right.”

It would be easy to cast this off as an isolated incident, but similar complaints about misleading pricing at Postmates and its competitors abound. These on-demand delivery startups won enthusiasm and big funding from investors by making the ultimate Uber-for-anything promise: stuff, brought to your door, at the touch of a button and for a nominal fee. But the price of instant gratification is rarely so cheap.

Postmates delivers from corner-store shops like Walgreens and retail brands such as Apple and American Apparel, but the bulk of its business is in traditional restaurant takeout. The company is valued at $450 million, and its delivery fees can easily top $10 for food that costs less. On DoorDash, a food delivery company last valued at $700 million, delivery is usually between $4 and $7. Uber-for-groceries startup Instacart charges as much as $12 for delivery on each order. It’s worth a whopping $2 billion.

Success in on-demand delivery means becoming a routine convenience rather than a luxury. But as the high and even exorbitant fees on Postmates and similar apps show, the economics just don’t work. On-demand startups are falling short of their founding promise to make instant-anything cheap, and they don’t want customers to know. That’s made prices on many of these platforms not just expensive, but also outright misleading.

Practically every company in the on-demand delivery space has spent big on coupons and vouchers to make its service seem reasonable, but other strategies go further. Caviar has a $15 minimum in New York City that it doesn’t reveal until checkout. Delivery and Caviar’s 18% service fee get added on top. DoorDash was slammed earlier this year for marking up restaurant prices in its app without any indication to users. Instacart previously used hidden markups on groceries to help offset operating costs; it made the system more transparent in April 2015 after customers protested, though prices are still inflated in some stores.

Postmates has tried to brand itself affordable with Postmates Plus, a network of about 3,000 merchants whose Postmates delivery fees cost $3.99 or less. It also offers Plus Unlimited, a subscription program that waives the service and delivery fees for orders from Plus merchants over $25. But at $9.99 a month, Plus Unlimited is still a luxury—more expensive on a yearly basis than a membership with Amazon Prime.

Pricing on other Postmates orders can be opaque, with subtotals often couched as ”estimates” and other fees added to that. In its service terms and conditions, Postmates cautions that it “reserves the right to determine final prevailing pricing” and that “pricing information published on the website may not reflect the prevailing pricing.”

Cook, a frequent Postmates user until his Walgreens order went awry, learned this the hard way. He’s not alone. Scan social media and you’ll find plenty of Postmates customers like Cook, who say the startup quoted them one price, then charged them something higher. Some discrepancies are more glaring than others, and just as many likely go unnoticed. After I mentioned this story to a coworker, he realized Postmates had recently charged him $17.83 for a burger-and-fries delivery from Shake Shack that it estimated would cost $13.63.

Consumer allegations of shady pricing offer a sharp contrast to the rosy picture that Postmates has presented of its business publicly. In March, Postmates said it was completing 1 million deliveries a month. In April, leaked financials indicated the company was making money on its deliveries, and its revenues were growing fast. That same month, Bloomberg reported that Postmates was in talks with investors to raise another $100 to $150 million in funding at an undisclosed valuation. Bastian Lehmann, the company’s founder and CEO, has said repeatedly that Postmates will be profitable by 2017.

Startups in the hyper-competitive food delivery space dispute the notion that their prices are anything other than above board. “We are 100% dedicated to price parity,” April Conyers, a Postmates spokeswoman, tells Quartz. “We are the most transparent company in the space.” After DoorDash was criticized for undisclosed markups that were atypical in the takeout industry, CEO Tony Xu told Bloomberg, “We don’t start a business by doing what everyone else does.”

Critics put it another way. ”I think the pricing of some of the food startups is borderline criminal,” says Matt Maloney, CEO of Seamless parent company Grubhub. “I think it’s absolutely disgusting the way they hide fees in order to fake profitability.”

On-demand delivery is a notoriously tricky business, its perils immortalized by the rapid rise and fall of instant-anything startup Kozmo during the first dot-com bubble. While the current wave of delivery startups was born in part of ”Uber-for-X” enthusiasm, their logistics-intensive operations are far more complex than matching riders with drivers. For any of these delivery platforms to work, they need to build out and maintain menus and inventory lists for thousands of individual merchants; track high volumes of daily orders; and run efficient dispatching systems.

What makes delivery even trickier—especially with food—is its thin margins. A typical grocery keeps $1 to $3 on every $100 a customer spends. Restaurant margins are usually around 5%, according to industry research firm Technomic. Most outside delivery services take a 15% to 30% cut for their services, but reaching the high end of that range requires being able to drive a lot of orders. Running a delivery business also isn’t cheap. Companies like Postmates and DoorDash spend heavily on promotions—discounts for customers, referrals and sign-up bonuses for workers that can cost hundreds of dollars apiece—as well as normal labor costs. To make delivery more lucrative, companies often have to pass the cost along to the customer.

Uber “disrupted” the taxi industry by offering a better service at a lower price. It’s much less apparent whether on-demand delivery startups can do the same. Companies like Postmates and Instacart are inherent middlemen selling Uber’s speed and app-based convenience without its clear cost advantage. Most consumers are only willing to pay so much. A report from Morgan Stanley Research in June found that 71% of people said they would spend no more than $5, excluding tip, for a $30 order of food that was “guaranteed to be delivered fast.” Fifteen percent said they refused to pay delivery fees at all.

Despite that, investors have placed big bets on delivery, especially with regard to food. They note that no one cooks anymore and point to a “secular shift” toward online and mobile ordering. In 2015, the market for home delivery and takeout grew to $22 billion, up 5.5% from the previous year, according to data from Euromonitor. Morgan Stanley Research believes that online food delivery “is still in its nascency,” with only about $10 billion of $210 billion in “core addressable restaurant spend” currently handled online. Grubhub, by far the leader in US food delivery, did $2.4 billion in gross food sales last year.

“The higher the frequency is, the easier it is for a customer to form a habit around a product,” Postmates CEO Lehmann told Quartz in February. “Getting food delivered, or delivery in general, and moving yourself around the city are the two huge things that we constantly do. Everything else is secondary.”

After his Postmates courier departed that Tuesday in June, Cook fired off an email to customer service. “Hi Postmates,” he wrote. “I’d like to report the following about my recent order from Walgreens: the subtotal was VERY different from the total amount.”

Over a series of emails, Postmates’ support team told Cook that his bill was accurate. They said Cook’s custom request for ibuprofen/Advil ($17.99), Postmates’ delivery fee ($6.50) and its 9% service fee ($7.25) accounted for the difference in price. But to Cook, the numbers still didn’t compute. Adding each of those charges to his $48.96 estimate brought the total to $80.70—still $13.54 short of what he had paid. He contacted support once more. A rep identified as “Kiara” responded, “I have confirmed your charges were correct.”

Other Postmates customers who spoke with Quartz were frustrated by similar experiences. MacKenzie Reid, a user in Kansas City, Missouri, described a mac-and-cheese order she placed from a local restaurant through Postmates in June. Postmates estimated Reid’s food would cost about $12; the company charged her card for $25.94 (a “pre-auth hold amount,” customer service later told her) and ultimately had her pay $18.10. ”It was sketchy from start to finish,” says Reid, who noted that she was unable to recover the estimated price to contest her final bill.

Conyers, Postmates’ spokeswoman, told Quartz that the company handles 1 million deliveries a month and the number of people who have trouble with pricing is ”very small” compared to “the amount of orders we do correctly.” She emphasized that discrepancies are more likely to occur when customers order from merchants who aren’t officially partnered with Postmates. “Restaurants that we’re partners with, pricing is typically right on target,” Conyers said. “There’s no question there because we have their menu; they keep us updated; there’s no exchange of payment when the Postmate gets there because it’s already been handled on the backend.”

Walgreens is an official Postmates partner. A spokeswoman for Walgreens told Quartz that the company provides Postmates with “a select list of products and pricing in order for Postmates to give customers a reasonable cost estimate.” However, she added, “product costs and availability can vary by location.”

Conyers says that Cook was charged exactly what Postmates paid. “Walgreens pricing varies store to store, so it’s possible that the amount we have in the app doesn’t match that exact store,” she wrote in an email. “That is why everything is listed as an estimate.” A receipt provided to Quartz shows that Cook was charged $10.49 instead of $6.49 for Tums, and $29.99 instead of $26.99 for Prilosec. Tax, which wasn’t accounted for in Postmates’ estimate, added $6.64.

Are those explanations good enough? Already, Postmates, DoorDash, and Caviar each have “F” ratings from the Better Business Bureau. Deceptive pricing is a recurring theme. After Quartz reached out to the BBB, Katherine Hutt, the bureau’s national spokeswoman, described the pattern of complaints as “concerning.”

“Customers expect that the price they see advertised is the price they’re going to get,” she said. “Legally it may be fine to bury in the fine print that the prices may vary, but that’s not a good way to have a healthy, trusting relationship with your customers, and we would like to see them have more transparent pricing.”

Money poured into venture-capital-backed food delivery companies throughout 2015, peaking in the fourth quarter when the sector attracted nearly $2 billion, according to VC research firm CB Insights. But financing has dropped precipitously since the start of this year, down to $320 million in the most recent quarter. That could bode poorly for startups that rely on subsidies to keep prices artificially low, new customers signing up, and old ones sticking around.

Signs of a shakeout are already plentiful. DoorDash in March sold shares at a 16% discount to its funding from a year earlier. The company isn’t profitable and has struggled with high turnover among its workers. Around the world, other food delivery startups are closing up shop: California-based SpoonRocket in March, India’s Tiny Owl in May, Belgium’s Take Eat Easy in July.

Food delivery startups are being forced to make a choice: Do they keep pushing subsidies and hiding the real costs of their operations until the money is gone? Or do they raise prices to make the economics work? Either way, these companies are in a bind. They promised too soon that instant gratification could come cheaply and are failing to, well, deliver on that. In a saturated market, the murky tactics used by Postmates and its competitors might still be good enough to get customers in the door, but are just as quickly pushing them out.

“All the places that [Postmates] could allow you to order from, they’re all starting to pop up on Grubhub and DoorDash, too,” says Cook, who deleted the Postmates app after his final exchange with customer support. “It’s not like they’re offering anything that I couldn’t get anywhere else.”