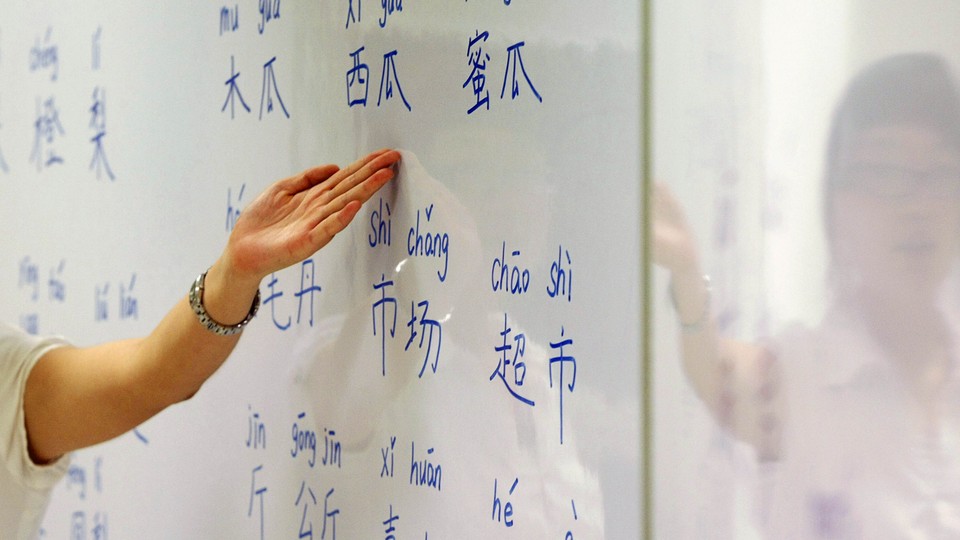

America's Lacking Language Skills

Budget cuts, low enrollments, and teacher shortages mean the country is falling behind the rest of the world.

Educators from across the country gathered in Washington, D.C., this past Thursday to lobby in the interest of world languages. It was Language Advocacy Day, an annual event on Capitol Hill that is aimed at garnering more federal support for language education.

As I sat in sessions and congressional conference rooms, I heard a persuasive urgency in these educators’ voices. Each year as national budget priorities are determined, language education is losing out—cuts have been made to funding for such instruction, including Title VI grants and the Foreign Language Assistance Program. And the number of language enrollments in higher education in the U.S. declined by more than 111,000 spots between 2009 and 2013—the first drop since 1995. Translation? Only 7 percent of college students in America are enrolled in a language course.

Another challenge emerges when looking at the languages these students are learning, too. In 2013, roughly 198,000 U.S. college students were taking a French course; just 64, on the other hand, were studying Bengali. Yet, globally, 193 million people speak Bengali, while 75 million speak French. In fact, Arne Duncan, the U.S. education secretary, noted back in 2010 that the vast majority—95 percent—of all language enrollments were in a European language. This is just one indicator demonstrating the shortcomings and inequalities in language education today.

Education is dominated by disputes over priorities, largely because of politics and limited funding. Some people, for example, think arts instruction is financial quicksand, while some believe that sports don’t belong in the schools. Others, meanwhile, even assert that schools’ emphasis on math could be holding students back. Language is another subject area whose importance is greatly debated. Advocates and educators disagree about whether it’s a worthwhile investment—whether it’s something that produces a greater return than, say, social studies. And within the realm of language, advocates clash over which ones should take precedence.

Less than 1 percent of American adults today are proficient in a foreign language that they studied in a U.S. classroom. That’s noteworthy considering that in 2008 almost all high schools in the country—93 percent—offered foreign languages, according to a national survey. In many cases, as Richard Brecht, who oversees the University of Maryland’s Center for Advanced Study of Language, said on Thursday: “It isn’t that people don’t think language education important. It’s that they don’t think it’s possible.”

Language proficiency is just as hard to build as it is to maintain. But the same could be said even about core subjects, such as math. Five years ago, I took Multivariable Calculus and Linear Algebra; now, I need a calculator to multiply four by seven. Still, my math classes taught me something more valuable than how to solve a complex equation: I learned skills that help me with the accounting, bookkeeping, research, and budget strategizing required in my day job. Like math, language-learning is shown to come with a host of cognitive and academic benefits. And knowing a foreign language is an undoubtedly practical skill: According to Mohamed Abdel-Kader, the deputy leading the DOE’s language-education arm, one in five jobs are tied to international trade. Meanwhile, the Joint National Committee for Languages reports that the language industry—which includes companies that provide language services and materials—employs more than 200,000 Americans. These employees earn an annual median wage of $80,000.

Kirsten Brecht-Baker, the founder of Global Professional Search, recently told me about what she calls “the global war for talent.” Americans, she said, are in danger of needing to import human capital because insufficient time or dollars are being invested in language education domestically. “It can’t just be about specialization [in engineering or medicine or technology] anymore,” she said. “They have to communicate in the language.”

The Joint National Committee for Languages advocates for integrating language education with subjects ranging from engineering to political science—anything, really. “Languages are not a side dish that’s extra, but it’s a side dish that complements other skills,” Hanson said. “You can use it to augment and fortify other skills that you have, and expand the application of these skills.” But students, especially those in college, are often discouraged from language courses or studying abroad because of stringent requirements in another subject matter.

But perhaps educational institutions can address this challenge by integrating language into their other programs. One solution cited by advocates is dual-language instruction, in which a variety of subjects are taught in two languages, thereby eliminating the need to hire a separate language instructor. At the elementary level, these programs appear to have immediate impact on kids’ learning. Bill Rivers, one of the country’s most prominent language lobbyists, points to significant evidence that students in dual-language programs outperform their peers in reading and math by fourth grade—regardless of their race or socioeconomic status. And advocates say dual-language programs are cost-effective because they typically don’t require extra materials for the language instruction; a science textbook, for example, would simply be published in the target language. That means districts buy the same number of materials as they would without the language element. The same goes for the number of teachers needed—though those teachers need to be bilingual as well.

Then there’s the question about what languages to offer. Roughly 7,000 languages are spoken worldwide, and it’d take a several lifetimes for any one person to learn them all. French and Spanish are often default offerings at institutions across the country, but beyond that, there’s a good deal of variability—and focuses have tended to change over time. Janet Ikeda, a Japanese-language professor whom I met on Thursday, put it like this: “Administrators are cutting established programs for what I call the ‘language du jour’.”

She’s right. Americans learn certain languages when, for example, emergencies hit. Slavic languages during the Cold War. Middle Eastern ones during the “War on Terror.” The Modern Language Association has tracked data over seven decades showing the influence of international and domestic developments on language education. But these pop-up programs may be misguided: Learning a language in a non-immersive classroom setting takes years. So if schools are offering learning the “language du jour” today, it’s bound to be the “language d’hier” tomorrow.

And then there’s the problem of teacher shortages. Even if schools embrace the various benefits of foreign-language instruction, finding qualified, experienced, and engaging, bilingual teachers in a crunch is tough. The language-policy analyst Rachel Hanson describes this as a big chicken-or-the-egg challenge in language education: “You can’t expand language education if you don’t have the pool of teachers to teach it,” she said. “And, if the students aren’t learning the language and becoming proficient, they won’t become teachers.”

Today, schools are having a hard enough time finding instructors in traditionally taught languages. In fact, the average proficiency of language teachers is below that needed by the military, Hanson said. But efforts to recruit qualified teachers to address the nation’s language deficit often face the additional obstacle of developing programs focusing on less-traditional languages. The list of languages designated by the federal government as “critical” include ones that many Americans have probably never even heard of before. There are more people in the world who speak Javanese than there are those to speak German, for example, and more who speak Lahnda than who speak French.

The country has faced shortcomings in language education for at least the past several years. Enrollments have been persistently low, as have proficiency levels; the same goes for non-Western language offerings. And with English as a lingua franca of trade and international politics, bilingualism has become less and less of a priority. True, many people speak English proficiently. But 19 million Americans and billions of people globally do not.

“It’s not a nice-to-have,” Rivers said. “Languages are a need-to-have.”