Once upon a time, the future of mental health treatment was drugs. The advent of Prozac and whole class of similar medication in the 1990s gave doctors an easy option and big pharma easy money.

But 20 years on, the problems have not gone away. In fact, mental illness is much more pervasive, with depression now the world’s second biggest cause of disability.

Moreover, a dramatic reduction in drug research and development suggests pills will not be the only – or even the primary – answer to mental health problems in the long term.

But what will be?

The laboratory

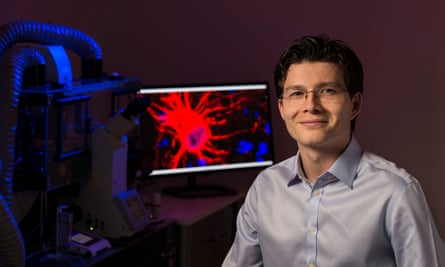

One reason Sergiu Pasca, assistant professor at Stanford University, went into research after completing medical training was his frustration when he saw what oncologists could do for their patients and how limited he and his colleagues were in treating mental health problems.

This was partly to do with the difference in funding for cancer and mental health research. But there was also the question of access.

“For cancer you can remove the tumour, and we can grow these cancer cells in a dish. If you find a small molecule that stops uncontrolled proliferation of these cells, you have a potential drug for cancer,” said Pasca. “In contrast with that, we don’t have direct access to brain cells, you can’t do a brain biopsy. Therefore, in studying mental disorders, we look at postmortem brains. That’s a problem for me as a neuroscientist because these neurons can’t fire,” he said.

Pasca’s laboratory has found a way to solve that problem, at least in part. Using stem cell technology, the team takes skin cells from living patients and from those develops a small spherical piece, up to 5mm in diameter, of functioning human cortical brain tissue. These small pieces, and there are thousands sitting in petri dishes in Pasca’s lab, have a structure very similar to the human cerebral cortex, the outer layer of the brain, and have neurons that fire.

Since these cultures have the DNA of whoever they are taken from, Pasca is able to compare brain tissue made from the cells of people with conditions such as autism and schizophrenia in the hope of working out how these conditions develop on a molecular level.

“It’s very likely that, as a community, we’re going to identify the causes, the mechanisms and probably specific therapies for particular forms of psychiatric disorders, pretty much like we’re doing for cancer today,” said Pasca.

The research is expensive and labour intensive, with each piece of brain tissue requiring about 20 weeks of almost daily cell culture work, but he believes it is likely to yield results, particularly for conditions that have a strong genetic component, such as autism, schizophrenia and forms of intellectual disability.

“In the next 10 years I think we’re going to understand more and more psychiatric disorders at the molecular level. I am convinced we’re going to witness a revolution in psychiatry,” he said.

The therapy

Dr Andrea Reinecke, clinical psychologist and researcher at Oxford University, is pioneering a new, and some might say tough, form of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). Her one-off sessions involve locking her patient in a cupboard so he or she can have, and get through, a panic attack.

In the first experimental study, which tested the impact of one-hour sessions of CBT on patients with panic disorders, all 30 patients showed improvement and one-third reported being completely free of symptoms a month later.

A second study combining the one-hour CBT with cicloserine, an antibiotic known to have a positive impact on neuro-plasticity, is about to be completed and looks set to report even better results.

The CBT session involves Reinecke talking to people with panic disorders about what prompts their panic attacks and about their coping strategies. Then Reinecke locks the patients in a cupboard, without access to any of these coping mechanisms, and let’s them go through a panic attack unaided.

This is important, according to Reinecke, because the brain starts to learn that it wasn’t the coping mechanism – breathing into a paper bag, calling a friend, or avoiding the situation – that prevented them from dying.

Teresa White, a carer from Oxfordshire, participated in the second trial, in March 2015. She had panic attacks for 20 years, which meant she couldn’t travel alone or be in a lift by herself. Even deviating from her regular dog-walking route would bring on a panic attack.

“I always felt like something bad was going to happen,” said White. “I was going to have a heart attack, I was going to pass out or I was going to die. I’d never actually been on a train by myself either until I’d done the study.”

White says the one-hour CBT treatment has been life-changing. “I can walk the dog anywhere I like, I’ve just recently done my first long-haul flight to the Caribbean, I went snorkelling, which is a big thing for me because of having a mask over my face. I can go in a lift by myself,” said White.

Reinecke said the speed and intensity of this treatment meant that not only was it cheaper, but also more patients saw it through. There is a high dropout rate for a typical 12-session course of CBT spread over six months.

“Whereas this goes for an hour, it’s one session where they have to push themselves, they can cry and scream and shout at me, but it’s going to work. It’s not only about cutting short but also about making things more effective,” said Reinecke.

So far, Reinecke is optimistic about the treatment’s effectiveness in the treatment of panic disorders, which affect 5% of the population. Her team is looking into whether it could also be used for other anxiety disorders and PTSD and within the next few years she will begin discussions with the NHS about running larger clinical trials in hospitals or at outpatient clinics.

The community

Five minutes’ walk from a tube station in east London, past an abandoned block of flats with broken windows, there is an unexpected three acres of calm.

Situated on a perfectly maintained park, where people sit reading on benches and a child kicks a ball with his grandfather, is the Bromley-by-Bow centre.

“A visiting priest said we had all the characteristics of a monastery except one,” said Dan Hopewell, director of knowledge and innovation at the centre. “We’re missing beer brewing.”

The feeling of a sanctuary is unsurprising – the centre was originally a church, which in the 1980s had a priest with a vision for serving the community of Tower Hamlets. Now, the centre is run as a secular charity – though the church still meets there – and houses a cafe, GP clinic, studio space for artists, a nursery, exercise and art classes, English lessons, employment and housing advice, and mental health support groups; and it models a very different approach to mental health care.

It hinges on the view that people’s mental wellbeing and social situation – in particular their ability to have purpose, community and not live in poverty – are intertwined and that addressing the latter can help to fix problems with the former. “How we live our lives, what we eat, who we talk to, all of these contribute to how we feel,” said Alice Everett, the centre’s social prescribing coordinator.

Everett works alongside local GPs to help people struggling with housing, finances, isolation and unemployment, which in turn affect their mental health. She often recommends people join programmes run by the centre, one of which is therapeutic horticulture, a weekly gardening group for people with mental health and intellectual difficulties.

“The group is fantastic, everyone’s so friendly and it does pick you up,” said Bill, one of the group members. “It really is good for your mind. If you miss a week you really miss it mentally.”

Bill has discovered he has green fingers. The landing of his flat is covered with pot plants, including begonias, which he describes as “my little babies”, though to his frustration they keep flowering pink. “I want some orange and red ones.”

For Matt Griffin, the programme that helped him was a sports and employability course for 18-35-year-olds with mental health problems. “I’d been very unwell with quite serious depression for a good year and a half. Doing the course gave me confidence,” said Griffin. “Coming in, interacting with people on a weekly basis made me feel more welcome, more able to do things.”

Since completing the programme early last year, Griffin has been employed part-time by the Bromley-by-Bow centre as a peer support worker.

These are just two examples of programmes the centre runs – “I work here and I still don’t know half the things we do!” said Griffin – but it is the ethos of the centre that marks it out.

“Our modern urban lifestyles are deeply unhealthy, not just because we don’t get any exercise, also because we don’t talk to anyone,” said Hopewell. “We’d say in deprived communities you don’t need a health centre that sits on its own, you need cafes, walking groups, art groups, things that bring people together.”

The Bromley-by-Bow approach is of interest to health professionals and governments around the world, attracting 1,500 visitors each year. The centre is advising the Well North programme, which is looking to introduce similar community centres across the north of England.

“It doesn’t matter if people are coming from Australia, Japan, Holland or Oldham, the issues are identical, their health services are under strain. Solutions don’t come out of consulting rooms, and don’t come out of hospitals, they come out of communities.”

The pharmacology

Even if the drugs pipeline is rather empty and big pharma is largely withdrawing, drugs will continue to play a role in treating mental illness.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as Prozac were in a sense a chance discovery, and the latest breakthroughs have also had an element of serendipity about them, the result of academic rather than industry experimentation.

The problem for drug makers is that the disorders are very complex, requiring much bigger trials than drugs for other illnesses, and have much higher failure rates.

And yet there are prospects. The pharma giant Allergan is to conduct phase III trials on a ketamine-like antidepressant that it says has rapid effect on major depressive disorder.

The Lancet recently reported that a small study found people with stubborn depression responded favourably to doses of psilocybin, an active ingredient in magic mushrooms. Another study found that the hallucinogenic substance ayahuasca helped alleviate symptoms in depression sufferers.

“Ketamine was pioneered by academics in New York, we’ve done magic mushrooms,” said Prof David Nutt from Imperial College London, referring to two recreational drugs found to have some success in treating depression. “These are small-scale experimental studies, but if we hit on something, Pharma might come back. Pharma are great at making drugs, we’ve to give them targets.”

What other promising treatments for mental illness have you come across? Let us know

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion