July 29, 2016

PHL Collective/for PhillyVoice

PHL Collective/for PhillyVoice

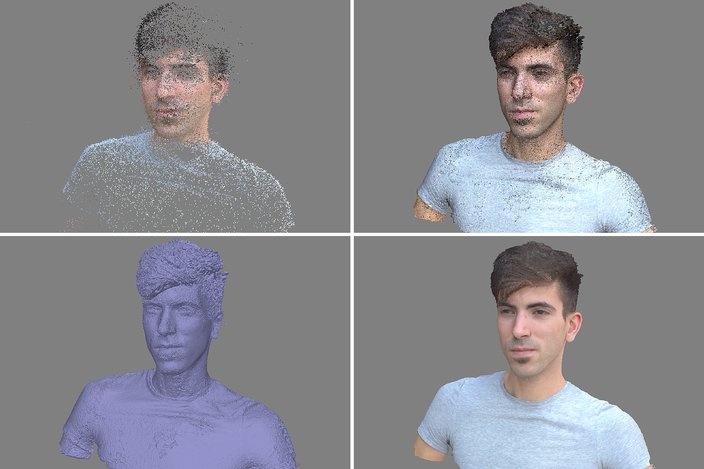

A 3-D model of writer Brandon Baker, partly shaded in using the 'Dense Cloud' algorithm of PHL Collective's photogrammetry software.

In the center of our eyes' retinas, in each and every one of us, is a "blind spot" — that is, a tiny little space in our optic nerves we never notice thanks to our body's own supercomputer: the brain. Which, in its infinite wisdom, fills in our vision based on everything else our eyes scan around that hole.

Apply that same fill-in-the-blanks concept to digital modeling, and suddenly you have a promising new method of creating graphics in video games. It's a new approach to game development being partly led by a studio in Philadelphia.

PHL Collective, a 2013-founded game studio of about six designers and programmers based out of String Theory Charter School, is using photogrammetry — a photography technique typically used for film, engineering or recreating crime scenes — to develop 3D models they'll use for characters and environments in their next video game, codenamed "Silverlake." That game will take a decidedly more realistic approach to graphics than the studio has taken with past games, like "ClusterPuck 99."

Which is where photogrammetry comes into play.

To demonstrate the process, PHL Collective scanned PhillyVoice writer Brandon Baker's head and transformed it into a 3-D model. From left to right, going clockwise: a 'tie cloud' version of writer Brandon Baker's head, taking an initial scan of all photo points that tie them together and into an image; the 'dense cloud' version of the model, in which the software fills in what's between each point of reference; a textureless 3-D model; a texture-added model, adding details as elaborate as stubble and clothing ruffles – the final step before being exported and further experimented with in design and animation software.

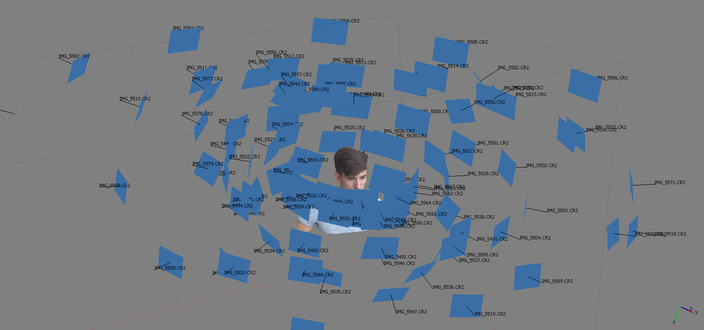

Here's how the technique works, in a nutshell: A developer takes photos of locations, objects and people from a variety of angles, being sure to overlap enough shots that a computer software program (Agisoft) can fill in the blanks — like the brain with a "blind spot" — and use points of reference in a real, 3D space to create a polygonal image. Designers then tinker with the image created, lower the polygon count (which can come in at more than a million) and then animate it, if so desired. In the process, it saves developers the time and money of creating a character model or environment from scratch.

Not to mention it allows for a degree of practical realism not present in a typical artist's mock-up.

Hundreds of photos are often taken of an object to get a fuller, more accurate image. Importantly, photos are taken from above, below, head-on and from varying distances to give photogrammetry algorithms spatial information.

"One of the things tough to do with environment art and level design is to create a realistic and natural-feeling environment," Bren King, environment artist for PHL Collective, told PhillyVoice. "The plus side to photogrammetry is you can go to, let’s say, a park, and you can scan the park by going on the outside perimeter of the park, taking photos inside and recreate that entire environment in 3D.”

By the time they're done, of course, scans have captured easy-to-miss details like dirt, pebbles and foliage that an artist wouldn't necessarily craft (or craft well) on their own. And, they've saved hours and reduced their carpal tunnel risk in the process.

The studio's use of photogrammetry happens to be fairly unprecedented. With the exception of Electronic Arts' "Star Wars: Battlefront," which released on major consoles last fall and scanned actual "Star Wars" film sets and costumes, no other noteworthy developer has attempted to create a game using this photo technique.

Why might now be the moment for photogrammetry, then? As one might expect, it has a lot to do with money and manpower.

“The practice has been around for awhile, but since cameras are getting a lot cheaper, and software is getting cheaper, and computer hardware in general is becoming cheaper, it’s becoming more accessible," King explained.

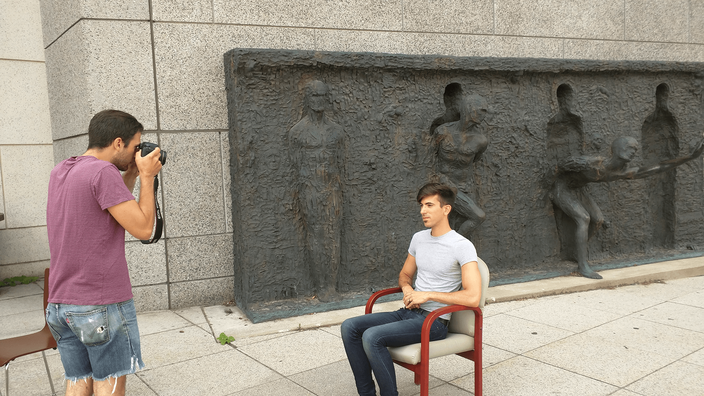

PHL Collective's Bren King photographs PhillyVoice writer Brandon Baker outside of String Theory Charter School. King captured more than 70 photos, with his subject sitting completely still, that were then scanned into photogrammetry software.

Moreover, PHL Collective founder Nick Madonna said, the technique is typically ill-suited for most major studios, between additional labor and skills required (like photography) and the cost of flying people to — and sometimes literally over, if aerial shots are being taken — remote locations being used in the game. (Madonna would know: He spent 10 years working for AAA studios like Square-Enix, Vivendi and Saber Interactive.) As a team of six, however, they're able to coordinate in a way bureaucratic companies can't — meaning other like-sized studios may jump on board in the future.

“I think, moving forward, a lot of studios will adopt a similar method — it’s just that we have an advantage of being a very small team, so we don’t have to manage 300 artists or 70 artists doing that same thing," Madonna said. "We can have a couple people doing this and not have bottlenecks of ‘How many cameras do we have?’ ‘Who do we have flying to take pictures of things?’ It’s a very manageable process with a smaller team.”

Concept art for the upcoming PHL Collective game, 'Silverlake.'

It also saves time: Though it takes hours to take the photos, upload and scan them, it can sometimes take weeks to develop a character or environment from scratch. And because the software itself isn't particularly expensive (camera equipment is, however), it expands what indie developers are able to do with their games.

PHL Collective will soon set up a photography studio with a green screen, scanning objects and clothed-to-their-choice mannequins to be used in "Silverlake" — a third-person-perspective online multiplayer game that, Madonna teased, takes inspiration from old-school horror movies and books. Photogrammetry will be used to not only create character models and woodsy environments but add realism to the game's cutscenes.

“We’re kind of putting together almost like an entirely other business to do photogrammetry for this game," Madonna said. "We’re all-in for this.”

PHL Collective/for PhillyVoice

PHL Collective/for PhillyVoice PHL Collective/for PhillyVoice

PHL Collective/for PhillyVoice Nick Madonna/PHL Collective

Nick Madonna/PHL Collective