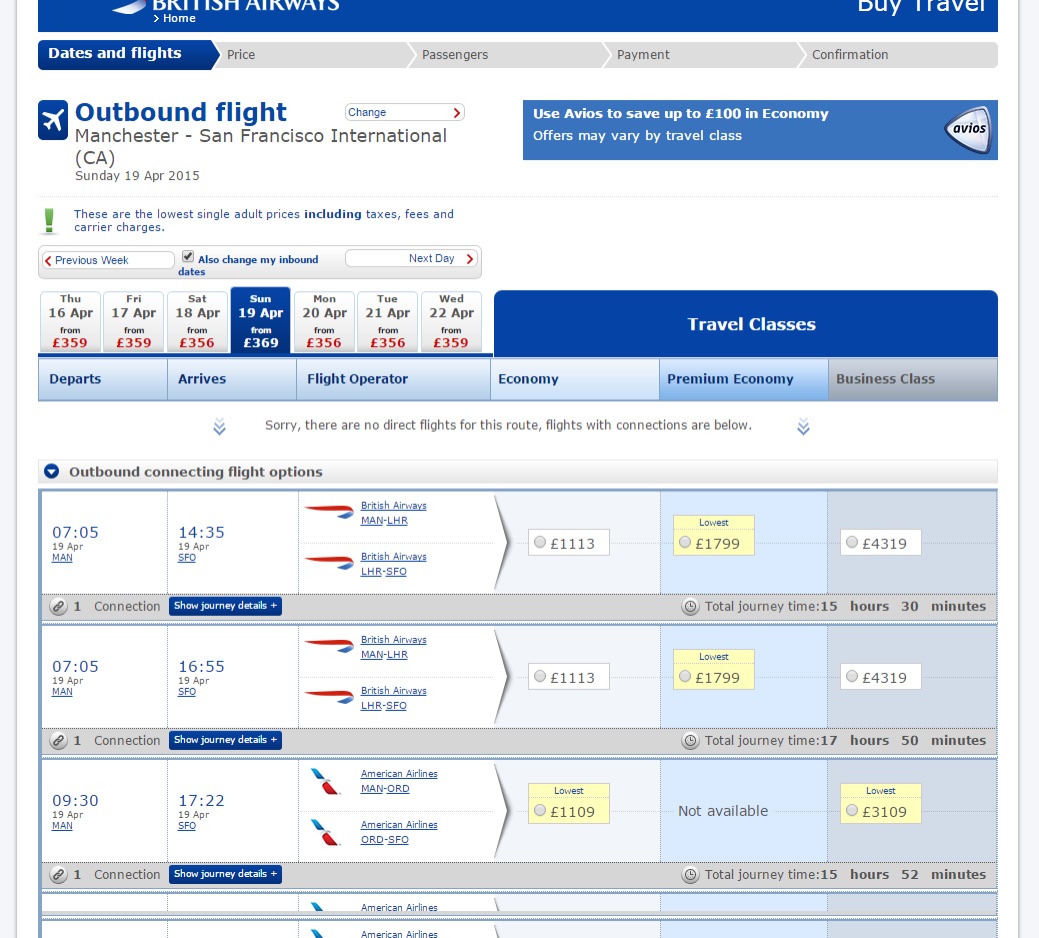

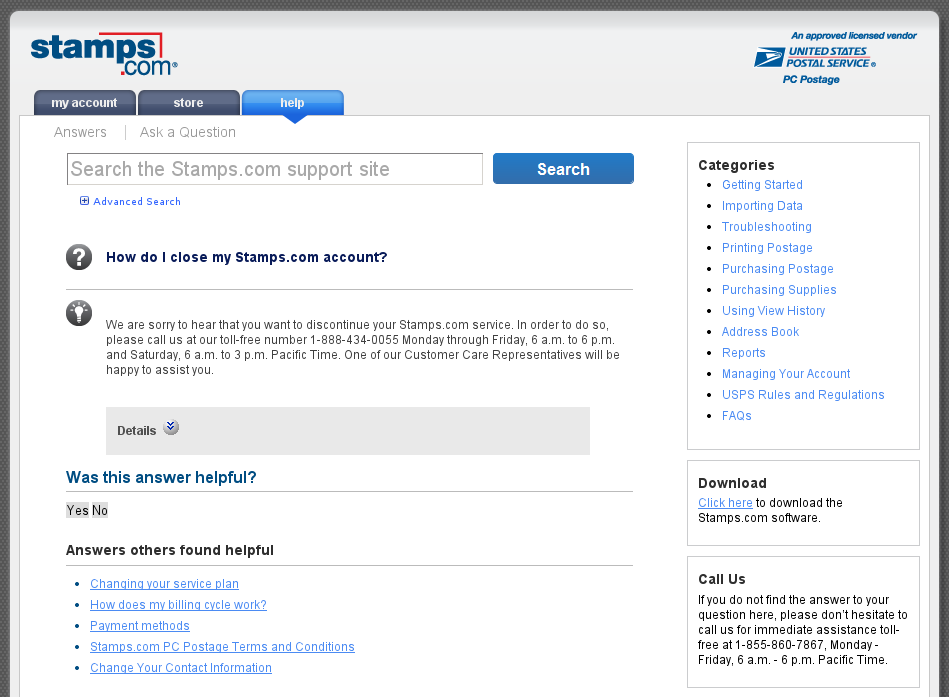

Everyone has been there. So in 2010, London-based UX designer Harry Brignull decided he’d document it. Brignull’s website, darkpatterns.org, offers plenty of examples of deliberately confusing or deceptive user interfaces. These dark patterns trick unsuspecting users into a gamut of actions: setting up recurring payments, purchasing items surreptitiously added to a shopping cart, or spamming all contacts through prechecked forms on Facebook games.

Dark patterns aren’t limited to the Web, either. The Columbia House mail-order music club of the '80s and '90s famously charged users exorbitant rates for music they didn’t choose if they forgot to specify what they wanted. In fact, negative-option billing began as early as 1927, when a book club decided to bill members in advance and ship a book to anyone who didn’t specifically decline. Another common offline example? Some credit card statements boast a 0 percent balance transfer but don’t make it clear that the percentage will shoot up to a ridiculously high number unless a reader navigates a long agreement in tiny print.

“The way that companies implement the deceptive practices has gotten more sophisticated over time,” said UX designer Jeremy Rosenberg, a contributor to the Dark Patterns site. “Today, things are more likely to be presented as a benefit or obscured as a benefit even if they’re not.”

Loading comments...

Loading comments...