In this post, Heather Mendick argues that some calls for slowing down scholarship mask a conservative politics.

Last July I blogged about how, despite my love for online communication, I worried that it was making me go faster and faster and so both changing what I do as an academic and turning me into the ideal neoliberal worker who churns out product rather than giving ideas time to mature. Shortly after I sent this blogpost out into cyberspace, the wonderful Maggie O’Neill from Durham University got in touch. She’d read my work in the context of the Slow movement and invited me to speak at a seminar on this theme. I was unaware of this movement, but decided not to let ignorance put me off, so I accepted the invitation and started my research.

A Manifesto for Slow Scholarship

I then turned my attention to slow academia. This extract below is taken from a Manifesto for Slow Scholarship:

“Slow scholarship, is thoughtful, reflective, and the product of rumination – a kind of field testing against other ideas. It is carefully prepared, with fresh ideas, local when possible, and is best enjoyed leisurely, on one’s own or as part of a dialogue around a table with friends, family and colleagues. Like food, it often goes better with wine.

In the desire to publish instead of perish, many scholars at some point in their careers, send a conference paper off to a journal which may still be half-baked, may only have a spark of originality, may be a slight variation on something they or others have published, may rely on data that is still preliminary. This is hasty scholarship.

Other scholars send out their quick responses to a talk they have heard, an article they read, an email they have received, to the world via a Tweet or Blog. This is fast scholarship. Quick, off the cuff, fresh — but not the product of much cogitation, comparison, or contextualization. The Tweetscape and Blogoshere brim over with sometimes idle, sometimes angry, sometimes scurrilous, always hasty, first impressions.”

While I can relate to the feeling of having sent out papers with half-baked ideas and with only a spark of originality (if that), I started to have doubts about the politics of slowness. The writers of the manifesto advocate slow blogs or slogs and slow tweets or sleets, ones that take time and are beautifully crafted. But this feels like a nostalgic rejection of the internet.

By insisting on slow blogs that you write just a couple of times a year and refine to perfection, you take all the fun and conversational-ness out of blogging and transform it into the (for me) difficult business of writing journal articles. But more than this you abdicate from a role as a public academic who joins in public debates as they happen, like I did when I jumped on Twitter after I saw domestic violence on Big Brother and wanted to participate in the struggle to name it as such.

A Call for Slow Scholarship

Next I read Yvonne Hartman and Sandy Darab’s 2012 article ‘A call for slow scholarship: a case study on the intensification of academic life and its implications for pedagogy‘. I found this to be more nuanced than the Manifesto as the authors embed their analysis in a wider understanding of neoliberalism. But I still had some issues with it. The quote here is used towards the end of the article. It’s taken from a Harvard academic’s letter to his students:

“Empty time is not a vacuum to be filled. It is the thing that enables the other things on your mind to be creatively rearranged, like the empty square in the 4 by 4 puzzle that makes it possible to move the other fifteen pieces around.

In advising you to think about slowing down and limiting your structured activities, I do not mean to discourage you from high achievement, indeed from the pursuit of extraordinary excellence. But you are more likely to sustain the intensive effort needed to accomplish first-rate work in one area if you allow yourself some leisure time, some recreation, some time for solitude.” (Lewis in Honore, 2004, 248)

This suggests that slowing down is mainly a way to be a more efficient and effective scholar, with slow scholarship directed towards the same aims as fast scholarship but offering a better way of getting there.

But don’t we need to be doing something a bit more radical than that? Shouldn’t we be seeking to challenge the goals as well as the means of academic life? And more broadly shouldn’t slow disrupt rather than reproduce the dominant definition of progress?

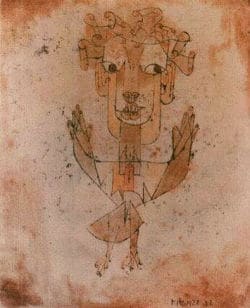

For me, the best evocation of the failure of progress is Walter Benjamin’s discussion of the Angel of History:

Is Slow Academia Conservative?

For these reasons, I have begun to feel that Slow academia is becoming a conservative movement – harking back to a ‘golden age’ of higher education that never was.

This post was initially published on the blog Celeb Youth.

Featured image by Dave Herholz (flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)