How the Tractor (Yes, the Tractor) Explains the Middle Class Crisis

A story about innovation, creative destruction, and how the mighty farm machine helped invent the modern U.S. economy.

Technology can kill jobs. Or, to put things more softly, it can replace certain jobs. Robot arms replace human arms in our factories. TurboTax does the work of tax preparers. We mourn the disappearance of these position even as we enjoy the most important consequence of the technologies, themselves: more useful goods and services at a lower price.

This is an article about an old job-killing technology. But the job that it made most obsolete wasn't the worker -- at least, not the kind of worker you're probably thinking of, nor the kind that the Bureau of Labor Statistics counts. This is an article about how the mighty tractor killed the farm horse. But it's also a story about how innovation replaces us, and how the economy can get bigger, faster, and stronger, while also making us feel obsolete.

THEY KILL HORSE JOBS, DON'T THEY?

In 1910, 25 million horses and mules -- one for every four U.S. citizens -- could roam the nation's farmland mostly free from technological competition. The tractor had been invented decades earlier, but the contemporary models were either ridiculously big or ridiculously expensive. The first commercial gas-powered units, sold in 1902, weighed more than a male elephant ... and they weren't much more affordable, either.

But this is how innovation works. First, we make new things, and then we make those things cheaper. The price and size of tractors fell rapidly over the next decade. Introduced in 1917, Henry Ford's smaller, cheaper "Fordson" was the iPad of tractors: the definitive, consumer-friendly genre-busting technology that immediately dominated a formerly desolate market. Round after round of new technologies -- power lifts, rubber tires, diesel engines -- eventually established a dominant model that made the 1940s the decade of the tractor.

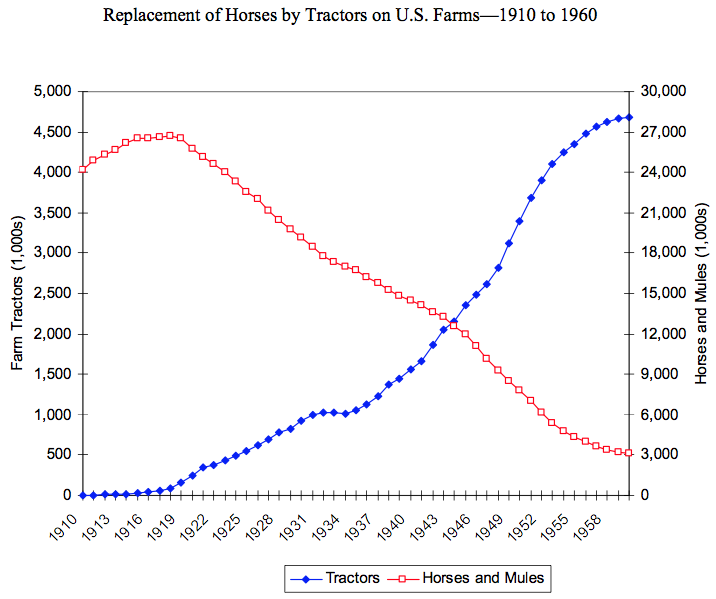

That decade spelled the end of the farm horse. One tractor could replace about the pulling-power of five horses or mules, agricultural historian Bruce L. Gardner wrote in his book American Agriculture in the Twentieth Century. Richard H. Steckel and William J. White produce this epic graph which plots the accelerating rise of tractors and the decline of horses through the 1950s.

When a technology comes along that threatens an American worker, the solution is to have the worker work harder. This idea is central to the Great Speedup thesis from Monika Bauerlein and Clara Jeffery in Mother Jones. Amazingly, or perhaps predictably, it was the same with 1930s horses. A 1935 economic paper published in the The American Economic Review titled "Tractor Versus Horse as a Source of Farmpower" noted that the only way in which horses could outperform tractors was if you worked them day and night to exhaustion:

Where horses are used little during the year, tractor power frequently is cheaper than horse power, even if prices of feed and horses are relatively lower than the prices of fuel and tractors. The reverse situation often occurs where the annual work per horse is large. Thus, the annual work per horse becomes a more important factor than the relation of the cost of feed and horses to the cost of fuel and tractors. The saving on labor which can be made by operating tractors instead of horses is significant in inducing farmers to shift to tractor power.

It would be churlish to suggest that the most important consequence of the tractor was the elimination of farm horse jobs. But one of the key ways that technology makes our lives cheaper is that it replaces the workers required to do a certain task. That's exactly what tractors did to horses. It's also what tractors did to people.

THE ROBOT FARM

You probably don't think about tractors very often. I sure don't. But that's just a sign that the tractor is doing its job.

The mechanization of agriculture (which was catalyzed by, but not confined to, the tractor) means we need fewer farmers to make more food every year. That has freed up people to work on the other stuff we care about, like consulting, and teaching yoga, and researching tractors.

In 1910, one third of our 92 million citizens and 38 million workers were on the farm. By 1950, only 10% of Americans worked on farms. By 2010, farmers accounted for only 2% of the workforce, even though we produce and export considerably more food. Machines took over the farm.

People are prices. And prices are, to a certain extent, people. When a given process requires fewer workers, its price usually goes down. As durable capital goods like tractors replaced expensive people and hungry horses on our farms, "farmers were able to reduce their costs and pass these social savings along to food buyers," Steckel and White write. The workers released from agriculture fueled our mid-century manufacturing revolution and our modern services economy.

The mechanization of the farm invented the modern U.S. economy. It made us richer, better fed, more productive, and more fully served by workers freed from agriculture. But the robots have moved off the farm, and the mechanization of the non-farm economy is currently one of the great challenges facing the middle class. In the 1940s and 1950s, workers released from farming duties went to build things to fill houses that needed refrigerators and other modern appliances.

Today's workers released from manufacturing's own mechanization and offshoring are having a harder time finding an industry to adopt them. The same is true for middle-skilled workers whose jobs have gone to software and foreign workers. Some of their plight can be explained by temporary weak demand. But much of it is also structural. It is the destructive part of creative destruction. Workers have been flowing away from our most productive (and most mechanized) industries like manufacturing and toward our least productive service jobs like nursing and teaching for decades now. This isn't bad. Nursing and teaching are valuable. But they're aren't very highly paid, and the result is millions of workers in local, low-value-added service jobs whose productivity ceiling is low and whose wages fall behind elites with the education to excel in a competitive economy. The pessimistic take on our employment crisis is that something has changed, and there is no modern manufacturing sector to absorb millions of modern replaced workers. The optimistic take is that we are simply living in the destructive valley of creative destruction, and the U.S. economy will continue to create decent-paying jobs, because it always has.

><